Symposium: The CyberPunk Culture Conference

Cyberpunk in the Modern Museum: Actuality, Future, and the Challenges of Exhibiting Movie Memorabilia *

Agnieszka Kiejziewicz

The young market of movie memorabilia is continuously growing, expanding on new thematic areas related to genre cinema and animation. A relatively short overview of this market highlights the lack of complete comparative price reports, as well as detailed academic analyses. The reports keep focusing on the most profitable auctions, such as the ones featuring the Delorean from Back to the Future (1985) or Robby the Robot from Forbidden Planet (1956) (Nevins, n.p.). Most of the accessible academic publications cover the initial wave of interest in movie memorabilia around the world, which was at the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s (Chaneles; Heide and Gilman). However, it is possible to assess the scale of the success of the market browsing through soft data, for example by juxtaposing the prices of movie memorabilia with fine art auctions over the years.

Together with increasing sales of memorabilia, the collectors organize exhibitions, aiming at reconsidering the notions of art and the possibility of introducing popular culture to the museums and galleries. Also, the exhibiting movie memorabilia raises the question of the aesthetic value of popular-art-related objects. An example of such an exhibition is the DC Exhibition: Dawn of Superheroes, which was shown among others in Łódź, Poland, and London, UK. In this context, it is symptomatic that the objects connected to film and animation changed their functions. Once, they were parts of scenography and popular culture, but now, they are displayed in the museums, considered as legitimate art. I leave the question on the sources of interest in movie memorabilia open, as the answer needs thorough sociological research, which exceeds the subject range of this article.

This paper stems from the experience of designing a concept of cyberpunk movie memorabilia exhibition that I developed together with Marek Kasperski, the owner of the Art Komiks gallery located in Warsaw, Poland (Kasperski, n.p.). Art Komiks administers the collection of over 300 objects classified as cyberpunk art, gathered by Polish collectors from auctions around the world. The collection contains objects related to cult titles, such as Ghost in the Shell (1995-2017; both animation and live-action film), as well as less-known titles from world cyberpunk – among the plethora of titles – New Hurricane Polymar (animation, 1996), Magnus, Robot Fighter (comic books franchise; 1963-2014), or Eat-Man (1997).

In this article, I am going to present the substantive issues related to the process of designing a cyberpunk movie memorabilia exhibition, as well as comment on the intermedia relations between the objects in the context of the overall concept of the display. It is worth adding that some of the ideas related to the exhibition narrative path were based on the findings presented in my book Japanese Cyberpunk: From Avant-garde Transgressions to Popular Cinema.

NEW MUSEOLOGY AND CYBERPUNK MOVIE MEMORABILIA

Modern museums search for unusual objects to gain a contemporary audience’s attention and, at the same time, create an interactive experience with (potential) educational values. It creates a situation in which the exhibitions are planned under measurable factors, such as potential income from tickets sold, attendance, and media response (i.e., journalists’ or bloggers’ reviews, number of views of the photo galleries published on Facebook and Instagram). Barron and Leask observe that museums are significant elements of cultural tourism, designed to be effective in gaining recognition and publicity. Researchers underline that institutions often ensure their future by, among other factors, enhancing the viewer’s engagement (Baron and Leask, 1-2). The value of novelty and shock, as well as the visible and easily recognizable connections to popular culture, diversify the audience, inviting to the exhibition space those who are not usually engaged in fine art displays. This wave of interest in expanding the notions of traditional art opens up an opportunity for movie memorabilia, comic art, and popular culture-related objects, such as bootleg art.

In this context, cyberpunk movie memorabilia and other art (comic book sketches, animation frames, photos, bootleg art, etc.) once perceived only as parts of cyberpunk narratives, changed their function. Now, away from the film scenography, the objects can be recognized by the contemporary viewer as sources of prophetic memory about the future and simultaneously gaining cult status because of their universal message. Movie memorabilia depicted in an art gallery can also be considered as a legitimate art, encouraging philosophical reflections about social development. It opens new research perspectives on the functions and objects exhibited in modern museums, expanding the definition of contemporary museology.

COLLECTING CYBERPUNK OBJECTS

Situating cyberpunk objects in the broader context of popular culture art collections, it should be noticed that they can be classified as movie memorabilia, comic art, game art, video games, books, autographs (i.e., autographed objects) and bootleg art. The collectors can reach a variety of forms through obtaining the objects from several different sources, such as auctions, directly from the authors, or the other private collectors. The uniqueness of the collection administered by Art Komiks stems from the model of support of the project, which is based on the contributions of the Polish private collectors, willing to lend the objects for the exhibitions.

As Marek Kasperski pointed out in a podcast about popular culture recorded for Deloitte (Kotecki), the process of building a collection of cyberpunk objects is related to a broader trend of collecting movie memorabilia, which is connected to the dynamics of income distribution between fans of popular culture narratives. Popular culture artifacts associated with nostalgia and trending superheroes universes for younger generations are gradually replacing the need of collecting fine art. Also, in the case of popular culture art, the act of building one’s own collection is less associated with gathering valuable possessions and increasing one’s material status. Instead, obtaining such objects is related to the need for the embodiment of passion towards particular narratives, heroes, or themes. Accordingly, the interest in the specific kinds of memorabilia varies – from the higher interest of the foreign customers in transnational cyberpunk narratives to the lower interest in local cyberpunk (for example the comic art created by Polish artists brings most attention from Polish fans and collectors).

CYBERPUNK EXHIBITION DESIGN

While designing the exhibition on cyberpunk, we found it essential to group the objects according to themes they covered, to provide the viewer with a clear, understandable path. Consequently, we divided the objects according to three main themes that reappear in cyberpunk narratives.

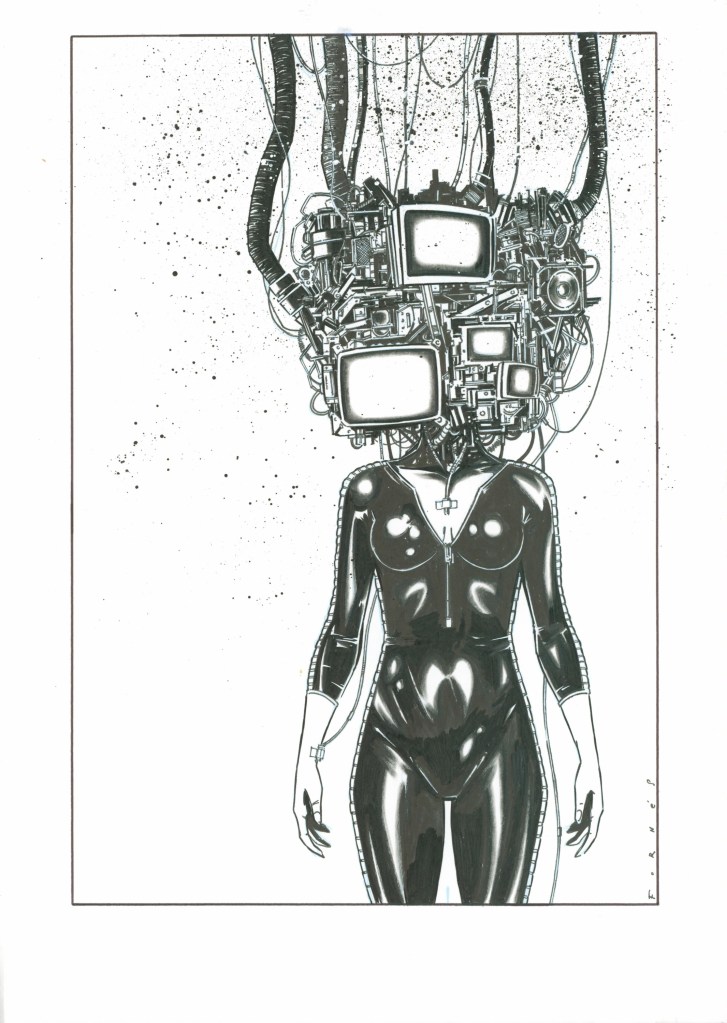

The first one revolves around the depictions of machines, androids, and cyber bodies, focusing on the protagonists under and after transgressive body metamorphosis. The impact of technology on human life, both in the context of the physical changes and the possibility of mental immersion in the virtual world, was the issue reappearing in the first literary cyberpunk narratives. The connection of the body to the machine, which became the basis of the intermedia genre, took various forms: from mechanical prostheses, replaceable organs, and under-skin hardware to interference in the brain. Cyborgizations were also a perfectly personalized, fancy arsenal of weapons attached to the user. In cyberpunk, the fusion of the body with the machine exceeds the limitations imposed by the imperfection and instability of biological tissue. The user strives for the ultimate defeat of death by improving physical capabilities or diving into cyberspace, thus leaving the imperfect body behind. Cyberpunk’s technology penetrates the biological tissue and leads to the disappearance of what the viewer recognizes under the concept of humanity. The protagonist of cyberpunk narratives uses the benefits of technological development, knowing that by bonding with the machine at the same time, he moves away from society, alienates from reality, and becomes the Other. An integral element of the fusion of man and machine is the terror of metamorphosis, the pain that accompanies the act of attaching the technological extensions to the biological organism. The appearance of an android reflects the possibility of comparing the determinants of human and machine existence, i.e., recognizing the features that distinguish an organic being from a mechanical one. This comparison also arouses the obsessive desire of conscious androids to confirm their existence by understanding what the soul is and whether an artificial creature can discover it.

According to the specter of works we (ArtKomiks gallery) have in the collection, we mostly focused on the terror of connecting biological tissue with mechanical cyber-improvements, at the same time discussing the new possibilities and powers gained by the characters. In this section, we also highlighted the place of the mechanical Other (android) in society. Here, among the objects we displayed, there is the head of the post-exploded android from Ghost in the Shell live-action film (2017) and animation art referring to this universe (i.e., the frames depicting the main character, Major Kusanagi’s mechanical body disintegration), Eric Canete’s covers from Cyborg comic books, Genocyber (1994) animation art or Tetsuo the Iron Man bootleg art created by Jaibantoys.

The second thematic area is focused on cyberspace and the world inside the computer. Here the narrative path followed such themes as the escapist nature of virtual surroundings or the moment of entering cyberspace and separating an imperfect biological body from an immaterial personality, thus introducing the dilemma of the existence of the soul and the Absolute. The division of the world into real and virtual has its roots in Jean Baudrillard’s reflections on a society immersed in simulations, wandering in hyper-reality, and manipulated by the media. The cyberpunk concept of cyberspace, inspired, among other things, by Baudrillard’s thoughts, was formulated and presented for the first time in the story True Names (1981) by Vernor Vinge. Since then, the vision of a cyber-world inside the Net has evolved, being successively developed with new plots showing the immaterial existence of a future man. The objects displayed in this section are, among others, photos from Johnny Mnemonic (1995) signed by Keanu Reeves, photos and the Atari game from TRON (1982) or comic art related to such titles as Magnus Robot Fighter (1963, reintroduced in 2010), Barb Wire (1994-1995), Godzilla: Cataclysm (2014) and Gall Force (1995).

Furthermore, the third section was dedicated to the depictions of a dystopian, futuristic city, including interior design. We underlined that a cyberpunk dystopia is a place of confrontation of corporations, subcultures, and residents of the criminal underworld. Despite technological development, a large proportion of the city’s future residents exist under challenging conditions, struggling with addictions and poverty. It turns out that advanced cyber implants only improve the lives of the privileged. Postindustrial dystopia, in which governments have fallen, and corporations have gained most of the decisive power, shows visible similarities to the reality behind the screen. As the plot of cyberpunk narratives takes place in the near future, the viewer recognizes fashion, architecture, and digital solutions, which they know perfectly well. The fall of order and social structures frightens, but also attracts with the mysterious beauty of the dark streets inhabited by the future man. The design of dystopia is a combination of space settlements, underground cities, and a vision of post-apocalyptic Earth after an atomic disaster, which is perfectly depicted by Severio Tenuta in his comic art from Heavy Metal, Dublin 2077 or by Syd Mead’s art.

Those three themes can be found in most cyberpunk narratives, though they function as a core for further thematic developments in the context of more prominent exhibitions. For example, the section about future landscape can be accompanied by insight into a dystopian fashion, not only highlighting film costumes from Ghost in the Shell, which we have in the collection, or weapons (i.e., a machine gun from Aeon Flux), but also depicting the comic sketches of the inhabitants of future cities.

CYBERPUNK BRANDS AND EXHIBITION PATH

On the level of recognition, cyberpunk artworks can be divided into those classified as big names, such as Ghost in the Shell or RoboCop, and less-known cyberpunk TV series or local comic art. Having in the collection examples of both categories, it is crucial to successfully merge the interest that the viewer will express towards the recognizable names with the artistic value that less-known narratives often offer. However, the big names will bring the most media attention and can serve as an incentive for potential media partners.

The appearance of big cyberpunk names should be considered while designing the narrative path based on the relations between the chosen objects and highlighted themes. For the viewers with partial knowledge about the genre, the media narratives (or the plots) associated with particular objects seem less important than the overall aesthetics of cyberpunk and the balance between the recognition of big names and the act of discovering less-known objects. Analyzing the practical implementations of exhibition design in several new media museums (i.e., in Finland, Sweden, Norway, Germany, and Poland), we contend that it could be discouraging for the viewer to read and learn every narrative separately and with a detailed plot. In this case, we adopted the approach in which the objects themselves tell the stories according to their placement in relation to each other.

INTMEDIA RELATIONS

It is worth underlining that media franchise titles such as Ghost in the Shell are accompanied by various kinds of objects (costumes, photos, drafts and sketches, props), whose presence underlines the intermedia relations within cyberpunk productions. Accordingly, we suggest that a narrative path should be based on clear connections, revolving around the variety of forms. For example, a cyberpunk weapon (accessory) and a sketch depicting this weapon or a frame showing a scene of using it can be showcased together.

We listed two elements that can underline the intermedia character of cyberpunk narratives, at the same time fulfilling the need for a clear exhibition path and creating a unique ‘cyberpunkish’ atmosphere. The first one is the influence on the audience and recognizability of a particular object. Mostly, it is the costume or a prop that appeared in the well-known film, which can be associated with the viewer with cult status. Also, the presence of 3-D objects (together with sketches and photos) draws attention to the production process. Furthermore, the second element is the meaning of the prop and its actual value, often enriched by an author’s signature or a certificate of authentication. We for example have Blade Runner‘s script signed by Rutger Hauer in the collection.

THE VIEWER

We are aware that the contemporary viewer, if they are not a fan of the cyberpunk genre, may not recognize all the authors, connections, and themes presented at the exhibition. Therefore, more than focusing on teaching people about cyberpunk’s visions in different media, we count on building a unique mood.

In this case, the cyberpunk movie memorabilia exhibition becomes a physical implementation of the conception of media diffusion in cyberpunk discourse. The variety of the gathered objects encourages the meditation on the character of modern times and the futuristic visions that became a palpable reality. For the viewer, cyberpunk narratives will function as the points of reference to fulfilled prophecies about the future. Entering the exhibition space filled with the artifacts from the cyber-world, the observer experiences the embodied futuristic dreams, or, referring to Baudrillard’s terminology, a heterotopia – an area on the verge of reality and imagination. In the optics of cyberpunk narratives, the technological solutions and aesthetics familiar to the viewer through their daily experiences are distorted, monstrous, and derived from their original context.

Cyberpunk movie memorabilia exhibitions show the manifestation of various names and media in cyberpunk discourse. The diversity of the collected objects allows the viewer to reflect on the nature of our times when visions of the future became a tangible present. Entering the exhibition, the observer gets familiar with films, comics, and game narratives currently functioning not only as a record of the creators’ imagination but also as a reference point to the prophetic visions of the development of modern societies. Futuristic objects and mechanical creations appropriating the body and perception of the individual reflect the everyday experiences of the observer, creating comparisons between the contemporary world and cyberpunk narratives. The exhibition of film memorabilia allows the viewer to confront the designed shape of futuristic visions by comparing it with what is known and familiar to them. Emphasizing the terror of transformation into a mechanical being, or recalling the post-apocalyptic character of the future, the creators of cyberpunk narratives are forcing the observer to verify contemporary social changes. Approaching cyberpunk aesthetics, we are balancing between technophobia and technophilia, unable to free ourselves from the need for creating comparisons.

CONCLUSION

The objects gathered within the collection, once treated as integral elements of cyberpunk narratives, have become records of the memory of the futuristic visions, striking the viewer with their universal character. At present, the fact of viewing the cyberpunk set of objects in the art gallery allows us to perceive them as a legitimate part of contemporary culture.

The successful merge of the exhibiting patterns reserved for fine art with popular culture objects opens a new field for discussion about the archiving and preservation of memory about contemporary media products. Also, the actuality presented in cyberpunk narratives, together with the excessive interest in the genre, expanded by the upcoming premiere of the Cyberpunk 2077 digital game, creates a need for revising the exhibition concept. The fact of showing cyberpunk movie memorabilia on display is a proposal addressed to two generations of viewers: those who seek for a nostalgic journey into the narratives from the beginnings of cyberpunk and those who have already started discovering the genre, encouraged by the newest productions.

NOTES

*All pictures used in this article come from Art Komiks’ archive.

WORKS CITED

Barron, Paul & Leask, Anna. “Visitor engagement at museums: Generation Y and ‘Lates’ events at the National Museum of Scotland.” Museum Management and Curatorship, vol. 32, 2017, pp. 1-18.

Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation, edited by Mark Poster. Stanford UP, 1988.

Castro, Adam-Troy. “Blade Runner Gun Auctioned for $270,000.” SYFY Wire, 2012, https://www.syfy.com/syfywire/blade_runner_gun_auctione. Accessed 5 November 2020.

Chaneles, Sol. Collecting Movie Memorabilia, Arco 1979.

N.a. DC Exhibition: Dawn of Superheroes Website. 2020, http://www.switsuperbohaterow.pl/. Accessed 3 November 2020. [in Polish].

Extended Museum in Its Milieu, edited by Dorota Folga-Januszewska, Muzeologia, Vol. 18. Universitas, 2018.

Holmes, Mannie. “Empire Strikes Back Stormtrooper Helmet Fetches $120,000 at Auction.” Variety, 2015, https://variety.com/2015/artisans/news/stormtrooper-helmet-sells-for-120000-at-auction-1201611983/. Accessed 3 November 2020.

Kasperski, Marek. ArtKomiks Website, https://artkomiks.pl/en/.

Kiejziewicz, Agnieszka. Japoński cyberpunk. Od awangardowych transgresji do kina popularnego [Japanese cyberpunk: from avant-garde transgression to popular cinema]. Kirin, 2018.

Kotecki, Wiesław. “Podcast: Człowiek Biznes Technologia by Wiesław Kotecki; #38 Marek Kasperski o sztuce [Podcast: Human, Business, Technology by Wiesław Kotecki; #38 Marek Kasperski about art.” Deloitte, 2020, https://www2.deloitte.com/pl/pl/pages/deloitte-digital/podcast-czlowiek-biznes-technologia/38-Marek-Kasperski-o-sztuce.html. Accessed 10 September 2020.

Lapin, Tamar. “Rare props from ‘Star Wars,’ ‘Batman’ and other classics up for auction.” New York Post, 2019, https://nypost.com/2019/08/20/rare-props-from-star-wars-batman-and-other-classics-up-for-auction/. Accessed 12 September 2020.

Lasiuta, Tim. Collecting Western Memorabilia, McFarland, 2004.

Oliver, Richard W., Lowry, Glenn D., and Terrence Rilely. Imagining the Future of the Museum of Modern Art, The Museum of Modern Art New York, 1998.

Nevins, Jake. “The world’s most expensive film props and costumes – in pictures.” The Guardian, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/film/gallery/2017/nov/27/the-worlds-most-expensive-film-props-and-costumes-in-pictures. Accessed 5 September 2020.

Vinge, Vernor. True Names, Penguin Books, 2016.