LSFRC 2021 Papers

Dystopias in the Trump Era: Anti/Immigration and Resistance in CALEXIT

Anna Marta Marini

Approaching the 2016 United States presidential election, writer Matteo Pizzolo developed the idea for a comic book that could reflect the growing political anxiety experienced in the Californian borderlands, as well as the reality at the United States-Mexico border. Drawn by Amancay Nahuelpan and published by Black Mask Studios in 2017, Calexit [1] (stylized as CALEXIT) is a dystopian story set in a near future, two years after the re-election of an autocratic president who ordered the deportation of all immigrants and deployed the National Guard to occupy sanctuary cities and enforce the law. The order sparked dystopian warfare between California’s liberal cities and conservative exurbs, respectively forming the Pacific Coast Sister Cities Alliance (including Tijuana) and the Rural Sovereign Citizens Coalition. Directly confronting both the National Guard and the neofascist vigilante Bunkerville Militia, an armed citizen movement called Mulholland Resistance fights for immigrant rights led by ruthless Zora Donato. Unwillingly involved in the conflict, smuggler Jamil—accompanied by his crow-shaped AI drone Livermore—is bound to take Zora to a secret militant camp on the border. In the attempt to annihilate the resistance and capture its leader, extremely violent confrontations ensue under the command of deportation enforcer Rossie—who at the same time lives with his Latinx wife and children in San Diego, raising the topic of existing Latinx conservative anti-immigrant stances as well. Filled with popular culture references, the comicbook directly engages with contemporary activist and political movements—evidently referring to the controversial notion of a “Calexit” [2] secession of California. The construction of the dystopian context outlines a forebodingly realistic fictional civil war within California, as parallels with actual extrajudicial border enforcement practices can be drawn. The collected edition is also rounded out with a series of interviews done by the author with local activists, political figures, and investigative journalists whose takes on the 2016 electoral campaign Pizzolo found valuable.

Make California American Again: Discourses of the Trump Era

Calexit’s plot starts halfway through the second mandate of a fictional unnamed president, whose authoritarian administration has focused on the deportation of any undocumented immigrant. As a consequence of California’s rebellion against the presidential executive order, any foreign-born citizen whose documentation was issued by Californian institutions is also bound to deportation, regardless of their status.

The references to Donald J. Trump’s 2016 electoral campaign and subsequent presidency are very clear, both visually and verbally. The comic book opens with a page focused on the president’s speech, announcing his upcoming visit to California and promising that he is not “gonna let murderers and illegals hold [American citizens] down” (3, Fig. 1). The few sentences evidently reproduce some of Trump’s most recurrent discourse strategies and speech patterns, including the use of an informal register. The reference to recognizable, widespread images depicting Trump at his presidential lectern is evident; possibly for its recurrency during his administration, this specific configuration of silhouette and suggested gesture has become one of the most used images on the internet, often turned into memes and mocking gifs.

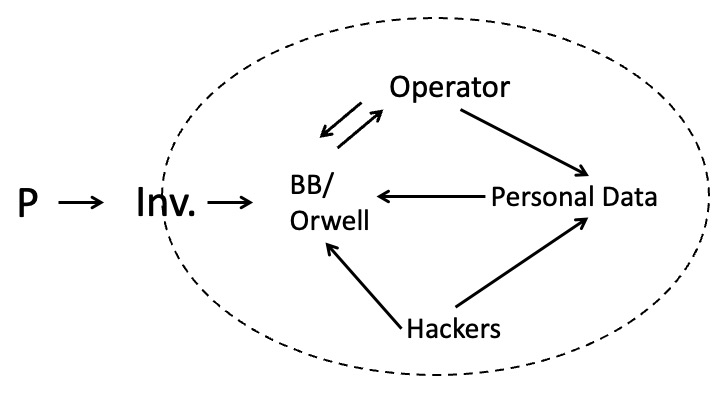

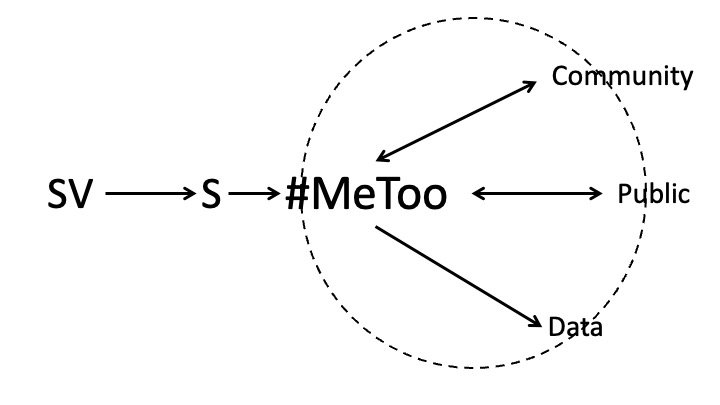

Right from the first page, a Manichean view of reality is outlined through the autocratic president’s words, just as it happened during Trump’s administration. Trump’s discursive strategies and patterns have elicited Orwellian comparisons (Rodden 261-263), and his administration was based on what Gardiner has called “demographic dystopia” or the notion of an impending demographic shift for which White citizens would soon become a minority in the American society (Gardiner 64-68). Such a conviction clearly shapes White nationalist and supremacist fears of a possible loss of the privileges intrinsic to the majority status, supporting the “anti-immigrant sentiment embodied by Donald Trump” (Chan 62) and the related historical anxieties peculiar to the dominant class. Furthermore, Trump’s penchant for discursive strategies related to populism and post-truth has helped structure concepts that, in a much dystopian way, “presuppose the existence of universally shared, accepted ‘truths’ pre-2016 which shroud the pre-Trump, pre-Brexit period in a myth of munificence and objectivity” (De Cock et al. 4). The constant mention of “fake news” and denial of patent facts gave a dystopian prominence to mis- and disinformation, favored by new technologies and the consequent false content manipulation and dissemination (Guarda et al. 5-6). The illusionary certainty that Trump’s discourse offered to the electorate—and kept on fueling throughout his mandate, despite the lack of concrete, effective action—“[fed] on and fortifie[d] a deeply emotional rejection of existing social elites, constantly affirming he will not stop at anything in the defence of ‘his’ people” (De Cock et al. 5).

A fundamental pivot of Trump’s discourse is embodied by the United States-Mexico border and immigration issues related to it, fueling—with the help of mainstream media channels—the rooted fears of an impending immigrant “invasion” and the “evidence” of crimes perpetrated by immigrants against American citizens. Drawing on Juri Lotman’s definition of the semiosphere and the expansion of it by scholars who have intersected it with the notion of political hegemonic discourse (see, for example, Selg and Ventsel, “Towards a Semiotic Theory of Hegemony”), I argue that the United States-Mexico borderlands can be conceived as the embodiment of the boundary of the U.S. cultural semiosphere—its peripheral part as opposed to the core embodied by the national Anglo monoglossic dominant heritage. In the dystopian scenario imagined by Calexit, the disruption and boundaries that intersect and characterize the peripheral part of the semiosphere become tangible. The clash between two factions that in a way exist in reality and cohabit the geographical, institutional space represented by California, in this dystopian take becomes so strained that the fracture is irreparable and a civil war ensues.

The type of dialectic discourse proposed by Trump embodies the discourse that aims at defining and preserving the semiospheric core. The dominant semiosphere is evidently self-descriptive, according to an idealized set of values, cultural references, and signs, which are reflected in a sociocultural hierarchy. Trump’s discourse exacerbates the preexisting U.S. political core discourse, that has been—often and more or less overtly—a nativist discourse. Policies focused on immigration and the border infrastructure have represented a central issue since the 1980s with the implementation of immigration regulation measures, followed by the start of the actual building of a border infrastructure in the mid-1990s. The turn of the screw represented by the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks strengthened the security measures at the borders, leading to the creation of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency in 2003. The Trumpian wall discourse is just an oversimplification, a symbol embodying this preoccupation with the definition of what is inside and what is outside the border of the U.S. semiosphere. The border is not directly shown on the pages of Calexit, but its presence is underlying throughout, as the notion of the boundary as a locus of invasion and disruption marks the story.

As Ventsel has stressed, politics “can be conceptualised as a practice for creating, reproducing and transforming social relations that cannot themselves be located at the level of the social” (9). Politics are a direct expression of the power of discourses, since problems related to the political sphere are intrinsically social, connected to “the definition and articulation of social relations in a field criss-crossed with antagonism” (Laclau and Mouffe 153). The necessity to affirm a “new” post-truth national identity intrinsic to Trump’s and his supporters’ discourse relies on the perceived necessity to reestablish the cultural homogeneity of the system, which corresponds to the U.S. dominant cultural core. Such perceived need of rearticulation of the core—and White culture as predominant—possibly “stems from the change of culture’s position due to its inner or outer factors. In most cases the main causes for intensification of identity creation are external effects” (Selg and Ventsel, “An Outline” 465). Clearly, the borderlands embody the external influences perceived as threatening, as the immigrants’ entrance and integration could lead to the tainting of American values and heritage.

Calexit does not only refer to Trump and his discourse, but also to the White supremacist groups that supported him throughout his mandate. Any operation that would be perceived as too controversial if carried out by federal institutions is handled by the Bunkerville Militia, a sort of vigilante group operating more or less overtly in connection with deportation officials. Its members are openly Nazi, they engage in local criminal activities, and they are characterized as indulging in drug use, prostitution, and in general violence, markedly masculine activities—despite the fact that the actual mind behind their new leader Crowbar is one of his girlfriends. When the National Guard accidentally tracks Zora, the agents directly call Crowbar to inform him, as he has been—extrajudicially—put in charge of the pursuit and capture of the resistant faction’s leader by Rossie. The chief deportation enforcer for the federal government purposely provokes extremely violent confrontations between the antagonist factions, in order to justify a consequent brutal intervention of the National Guard. He is ruthless and collaborates directly with the Bunkerville Militia to get the “dirty work” done, but he also visits members of the Mulholland Resistance to convince them of the uselessness of their fight—thus fomenting internal division. Significatively, at the same time Rossie’s private life contradicts his ideological convictions: he has a Latinx wife and children who live in a secluded villa in San Diego. This raises the topic of the existence of Latinx conservative anti-immigrant stances, since his wife is a stern supporter of his job and its consequences. The comic book delivers a not too veiled reference to public figures who promote discourses and ideologies that do not necessarily correspond to their personal life, and in general the double standards that often characterize the political elite.

Extremism and Dystopic Resistance

Dystopian narratives have been characterized by the attempt to identify “a utopian horizon that might provoke political awareness or effort” (Moylan 163), a motive that might elicit political resistance against the grim scenarios in which the characters are forced to move. Dystopian resistance upholds forms of what Moylan has defined as “utopian hope,” contemplating the possibility of radical social change based on the resistant characters’ refusal to abide by the rules imposed by the dominant strata of society. Clearly, not all approaches to resistance bear the same commitment or lead to the same achievements. Building on Baggesen’s notion that dystopian pessimism and its consequent reactions can be either resigned or militant (Baggesen 36), it can be argued that the construction of most dystopian narratives revolves around the opposition between an imposed hegemonic order and a counter-narrative resisting the dominant system. In particular, the dystopian fiction focusing on the construction of a totalitarian regime lends itself to parallels with reality and the articulation of storylines that draw on political action and its ethics. As Jones and Paris’s study has demonstrated, “totalitarian-dystopian fiction heightens belief in the justifiability of radical political action” (982). Faced with dystopian narratives, the study subjects’ responses highlighted the fact that in such circumstances violence seems necessary and even legitimate to subvert the totalitarian system (982-983). Due to the political charge of the narrative and the articulation of the opposition to the violation of values of democracy and equity, the performance of acts of resistance is often portrayed “as admirable (even when not or only partially successful) and readers are expected to empathize with the protagonist and even imagine how they themselves might fight such value violations” (972). Furthermore, gendered dystopian fictions seem to be marked by “a subversive and oppositional strategy against hegemonic ideology” (Baccolini 519). The construction of Zora’s character seems to be purposely exaggerated toward violent extremism to convey the main idea underlying the comic book: alleged neutrality does not exist, as inaction and refusal to take a stance is per se favoring the totalitarian system.

In the premises of Calexit’s story, it is said that the “ultimate betrayal” triggering the repressive occupation of California and the reaction of the local conservative fringes is the fact that the Pacific Coast Sister Cities Alliance—besides being formed by sanctuary cities in the U.S. territory—also included Tijuana. The inclusion is seen as inadmissible by the White supremacist, nativist segments of Californian society. In the detailed reconstruction of the dystopian context written by Pizzolo, when Tijuana joined the alliance the president felt that he could “no longer tolerate what is becoming an international conflict and decide[d] he must invade California” (106). The main character voicing this type of discourse is the enforcer-in-chief Rossie, who is leading the occupation and exploiting a paramilitary group such as the Bunkerville Militia to make the most of the local conflict. Through Rossie, the government delegates operations to an extremist civilian organization, to resolve situations by violent means that would be extrajudicial for the state to exert—even within a state of exception. Contextualizing the comic book and its dystopian depiction of an ongoing, real political climate, such delegation reminds of the existence of civilian vigilante groups patrolling the United States-Mexico border. This kind of organization started to appear along the boundary in the mid-1970s and falls within the spectrum of so-called neo-vigilantism (Brown 127-129), as they involve some types of cooperation with the federal and local enforcement. Among them, it is worth remembering the Minuteman Project, which attracted the attention of the media in 2005. Part of the broad anti-immigrant movement, these groups are unauthorized and yet to an extent condoned by border enforcement agencies such as the Border Patrol and ICE. As Doty has highlighted, the civilian border patrols interpret the border as “a war zone” and prominently employ imagery and rhetoric inherent to war and combat (125)—as the members of the Bunkerville Militia do.

Opposite the Bunkerville Militia, the Mulholland Resistance is a movement constituted by citizens fighting for immigrant rights and led by Zora Donato, who is a queer and now-illegal Mexican immigrant cyborg. She lost a leg in a past confrontation, she is very assertive and convinced of the necessity to fight the state repression and extrajudicial deportation with any possible means. The comic book starts with a sequence in which her adoptive parents are threatened to make them reveal her location; as a consequence of their reluctance, her father is killed and his head is sent to the resistance group in a box. Besides being marked by harrowing experiences, Zora is depicted as an extremist figure. If the resistance on the one hand is armed and its components defend themselves violently against the National Guard and the militia, on the other hand she does not know where to stop. During confrontations she does not stick to the agreed plan to just repel the guards without attacking them and without provoking an exchange of fire. On the contrary, she attacks the guards first, provoking the killing of several members of the resistance.

Zora’s stance is first made clear in a dialogue with a fellow activist, taking place on the ruins of a house whose militant owners were shot to death in a conflict that escalated when she opened fire on the National Guard. While her companion is appalled by her minimization of the casualties and insists that militants “won’t fight, certainly not if they think we’re just throwing bodies at the occupying army” (68), Zora opposes his view. She explains that—as it happened “in the French-Algerian war”—casualties among the resistance fighters serve as inspiration for others to join the cause, and thus more people will take part in the fight out of indignation if they see militants die (68, Fig. 2).

When Zora and Jamil are stopped at a road check—and the guards communicate their location to the leader of the Bunkerville Militia—she reacts by shooting one of the guards in the face and the reader is left with the two of them waiting for the confrontation with the militia. A dialogue ensues between them, and the smuggler realizes suddenly that the Mulholland Resistance was not aiming to get Zora to safety at the camp on the border. Rather the group was trying to get rid of her due to the damages she provoked, as her extremist views and approach to the resistance have been revealed to be too dangerous for them. If this explanation exposes the questionable consequences of her uncompromising stance, Pizzolo does not condemn them. Her character is, to an extent, constructed around the aforementioned perception of the admirable value intrinsic to the fictional dystopian resistance, whose violent acts are justifiable when perpetrated against repressive opponents. The framing of her violent resistance within the totalitarian order allows—and leads—the readers to reconcile to its consequences and accept her violent yet nearly suicidal mission.

Of Monsters and Caves: A Criticism of Neutrality

In between the two extremes represented by the Bunkerville Militia and the Mulholland Resistance, Jamil embodies the subjects that—despite being to an extent involved daily in the conflict—do not want to take a clear stance and thus juggle their relationships with both factions. Unwillingly involved in the conflict, Jamil is a smuggler working for whoever pays him, often providing National Guard agents with antidepressants and illegal drugs. He knows his way around the conflict areas, and he can move freely between the territories controlled by either the resistance or the National Guard. Albeit suggesting a critical view on the enforced occupation, Jamil seems to embody a kind of character that recurs in dystopian fiction, who “negotiate[s] a more strategically ambiguous position somewhere along the antinomic continuum” (Moylan 147).

On several occasions throughout the comic book, Jamil stresses out that he does not care to express a political position, he maintains connections with both factions for business, having “problems with no one,” and that he is in the “not-making-enemies line of work” (53).

This approach of course provokes a clash with Zora, leading to an argument during which she justifies her extremist position and plans to fight her antagonists (102-103, Fig. 3). She believes that a violent insurgency is necessary to stimulate awareness in the public and that it is necessary to face directly the enemy, or “monsters” as she calls them, otherwise nothing will ever change. She accuses Jamil as being delusional—as other people like him are—and she says “you wanna believe if you’re just patient, everything will go back to normal. If you’re just patient, the monsters will go back into their caves” (102). She clearly hints at the fact that White supremacist groups cyclically resurge and that they are never really defeated, punished, or condemned by the dominant core of the US cultural semiosphere. When Jamil says that he is “fucking neutral. That’s my job,” Zora replies that her job is to make “sure no one’s neutral” (102). Not taking a stance would already be a non-neutral position per se, but she highlights the fact that he sells drugs to depressed extremists while telling himself that that is a neutral position.

Despite his reluctance, it becomes impossible for Jamil to avoid getting involved in the conflict and, consequently, being forced to take a position in it. Unwittingly, Jamil happens to be the person in charge of delivering the severed head of Zora’s father to the resistance; militant members thus leverage his involvement to trick him into removing Zora, lying on the plan to smuggle her to a secret camp on the border. Shortly after being caught by the National Guard, he unwillingly stands by her side, assuming the political weight of his purported neutrality and eventually taking a position. The main message of the comic book seems to be, indeed, a condemnation of self-declared neutrality and a denunciation of the real consequences of the refusal to position oneself, especially for personal interest or individual “peace of mind.”

The conflict articulated in Calexit is based on a power asymmetry between the totalitarian core and the dissident boundaries of the fictional semiosphere it is set in. It is political, cultural, and ideological altogether, and it touches upon shared values and ethical issues; the deliberate avoidance to take a stance would betray implicitly a connivance with the dominant side of the conflict. The construction of the dystopian context outlines a forebodingly realistic fictional civil war within California, as parallelisms with actual extrajudicial border enforcement practices are evident. Despite the violent scenario, Calexit brings to life a dystopia aimed at celebrating the spirit of existing pro-immigrant resistance and—in Pizzolo’s words—encouraging the readers to “look fascism in the face and challenge it” (CALEXIT 109; “2017’s most dangerous comic”).

NOTES

[1] For the purpose of this paper, the collected edition of CALEXIT (published by Black Mask in 2018) will be used as reference.

[2] For a brief recap of the debate channeled by the Yes California independence campaign (2015) see for example Chloe M. Rispin, “Could California Secede? A Philosophical Discussion.”

WORKS CITED

Baccolini, Raffaella. “The Persistence of Hope in Dystopian Science Fiction.” PMLA, vol. 119, no. 3, 2004, pp. 518-521.

Baggesen, Søren. “Utopian and Dystopian Pessimism: Le Guin’s ‘The Word for World Is Forest’ and Tiptree’s ‘We Who Stole the Dream’.” Science Fiction Studies, vol. 14, no. 1, 1987, pp. 34-43.

Brown, Richard Maxwell. Strain of Violence-Historical Studies of American Violence and Vigilantism. Oxford University Press, 1975.

Chan, Edward K. “Race in the Blade Runner cycle and demographic dystopia.” Science Fiction Film and Television, vol. 13, no. 1, 2020, pp. 59-76.

De Cock, Christian, et al. “What’s He Building? Activating the Utopian Imagination with Trump.” Organization, vol. 25, no. 5, Sept. 2018, pp. 671-680.

Doty, Roxanne Lynn. “States of Exception on the Mexico–U.S. Border: Security, ‘Decisions,’ and Civilian Border Patrols.” International Political Sociology, vol. 1, 2007, pp. 113-137.

Gardiner, Steven L. “White Nationalism Revisited: Demographic Dystopia and White Identity Politics.” Journal of Hate Studies, vol. 4, no. 1, 2005, pp. 59-87.

Guarda, Rebeka F., et al. “Disinformation, Dystopia And Post-Reality in Social Media: A Semiotic-Cognitive Perspective.” Education for Information, no. 1, 2018, pp. 1-13.

Jones, Calvert W., and Celia Paris. “It’s the End of the World and They Know It: How Dystopian Fiction Shapes Political Attitudes.” American Political Science Association, vol. 16, no. 4, 2018, pp. 969-989.

Laclau, Ernesto, and Chantal Mouffe. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. Verso, 1985.

Lotman, Juri. “On the Semiosphere.” Sign Systems Studies, vol. 33, no. 1, 2005 [1984], pp. 205-229. Translated by Wilma Clark.

Moylan, Tom. Scraps of the Untainted Sky: Science Fiction, Utopia, Dystopia. Westview Press, 2000.

Pizzolo, Marco. “2017’s Most Dangerous Comic: Writer Matteo Pizzolo on Golden State Secession Series Calexit.” Interview by Will Nevin. AL.com, July 11, 2017. http://www.al.com/living/2017/07/2017s_most_dangerous_comic_wri.html. Accessed 15 Oct. 2021.

Pizzolo, Marco, writer, and Amancay Nahuelpan, artist. CALEXIT. Black Mask Studios, 2018.

Rodden, John. “The Orwellian ‘Amerika’ of Donald J. Trump?” Society, no. 57, 2020, pp. 260-264.

Selg, Peeter, and Andres Ventsel. “Towards a Semiotic Theory of Hegemony: Naming As Hegemonic Operation in Lotman and Laclau.” Sign System Studies, vol. 36, no. 1, 2008, pp. 167-183.

—. “An Outline for a Semiotic Theory of Hegemony.” Semiotica, vol. 182, no. 1/4, 2009, pp. 443-474.

Ventsel, Andreas. Towards Semiotic Theory of Hegemony. Tartu University Press, 2009.

Anna Marta Marini is a Ph.D. fellow at the Universidad de Alcalá, where her main research project delves into the representation of border-crossing and the “other side” in U.S. popular culture. Her research interests are: critical discourse analysis related to violence (either direct, structural, or cultural); the representation of borderlands and Mexican American heritage; and the re/construction of identity and otherness in film and comics, particularly in the noir, horror, and (weird) western genres. She is currently the president of the PopMeC Association for US Popular Culture Studies.