Media Reviews

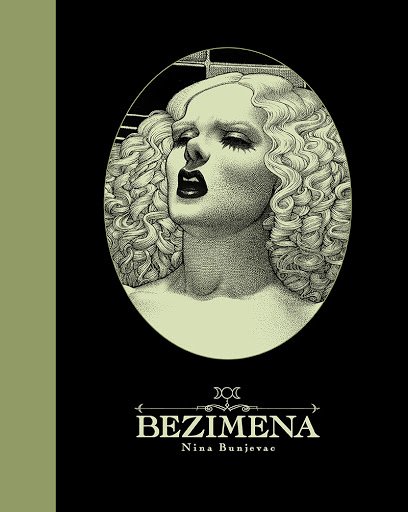

Before I get to specifics, readers should be warned that this graphic novel includes explicit sexual imagery and disturbing themes: it focuses on issues of sexual violence and consent. It tells the story of a young man who follows a woman home after finding her lost sketch book. When he discovers that the sketchbook includes graphic depictions of him engaging in sex with her and with others, he enacts the scenarios. By the end of the book, we are told that, in fact, the sketchbook belonged to a young girl who was sexually assaulted and murdered, along with two other girls, apparently by our protagonist. Readers who find this subject matter distressing should beware, and anyone should think carefully about whether this is an appropriate book for classroom use.

Bezimena, Nina Bunjevac’s third graphic novel, is an extended surreal narrative in which the line between reality and fantasy is not so much blurred as obliterated. Bunjevac identifies the myth of Artemis and Sipriotes, the gender-bending tale of Sipriotes being punished for an attempted rape by being transformed into a woman, as an inspiration. The book also echoes the myth of Diana and Actaeon, the voyeur transformed into a stag and torn apart by his own hunting dogs after seeing the naked Diana bathing in a pool. The fable of the king who puts his face into a bowl of water, finds himself in another world and another body, living another life until he removes his face from the water and is restored to himself, is also a clear inspiration. Fairy tales, especially ones such as Little Red Riding Hood, also inform the action. The work is dense, complex, and allusive—as well as elusive—requiring readers to try to make sense of the story themselves, rather than spelling it out.

The work’s obliqueness is evident from the beginning, in the frame device of two disembodied voices—the only voices to speak in the entire text—whose dialogue consists of the story we read as told by one to the other. The voices manifest as word balloons on black pages, one speaking from “below” the page (the tale-teller) and “above” the page (the auditor). We know almost nothing about who they are or what their relative locations mean. The tale teller recounts the story of a priestess who indulges in the habit of “perpetual and needless suffering” until Bezimena thrusts her face into the pool (or perhaps river—again, readers are left to judge, and how one interprets the moment may vary depending on what sort of body of water one assumes this is) by which she has prostrated herself. This act causes her spirit to separate from her body and to be reborn into a male infant in an entirely different environment, an uncannily detailed yet unidentified European city in what appears to be the early twentieth century. The boy, Benny, is an obsessive voyeur and masturbator whose childish fixation with fellow classmate “White Becky” re-emerges when, as a young man working at the zoo, he sees a woman he is sure is “White Becky.” The similarity of the names Benny and Becky, and the overt symbolic implications of the epithet “White,” are among the many ambiguities of this text that invite readerly. It is her notebook that “Becky” perhaps loses (or perhaps deliberately abandons) that serves as the catalyst for the tale. Impossibly, the sketchbook depicts events before they have happened—sexual fantasies involving voyeurism, bondage and arguably non-consensual sex—that Benny feels compelled to act out exactly as they are illustrated.

Here, perhaps, is the book’s most overtly metafictional and fantastical conceit. Bunjevac’s art is meticulously detailed, using heavy stippling to create an almost photographic effect. Most of the pages feature single images, and all the pages with pictures are devoid of words: the narrative voice occupies the verso pages, otherwise black, while the accompanying pictures appear on the recto pages, though there are occasional wordless, two-page spreads. The illustrations also frequently frame or enclose the figures, foregrounding our recognition that they are pictures, even as they depict events. Though the pictures depict actions, they are also frequently designed to appear staged and static—as drawings, rather than as depictions of life. The line between the sketchbook Benny finds and the story we are reading largely vanishes as we read.

Even the blurred reality thereby created is further compromised with the narrative twist that occurs when Benny is arrested on suspicion of murder, and the sketchbook suddenly transforms into one filled with a child’s drawings, not with the explicit sexual images Benny has seen and used to enact his fantasies. All evidence to support Benny’s version of events disappears, in effect, and readers are left to determine whether he has fantasized the whole thing, rationalizing his murders with his elaborate scenario, or whether he has been victimized by some inexplicable force. The frame narrative of the priestess apparently being punished for her self-inflicted needless suffering, the unidentifiable disembodied voices sharing the tale, and the various myth and folk echoes certainly invite readerly speculation.

Indeed, the most intriguing thing about this book, perhaps, is its interpretive openness—though that is arguably also its most disturbing characteristic. In an afterword, Bunjevac offers a personal account of two sexual assaults she suffered, inviting readers to contextualize what they have read in light of real-world sex crimes. However, the book is far from a dogmatic or polemical critique of rape culture, Instead, it raises troubling questions about desire and gender. What one is to make of the fact that the putative rapist/murderer is represented as being the spirit of a female in a male body remains open. How one is to read White Betty—a virginal victim, a temptress who takes pleasure in the transgressive sex imaged in her sketchbook, a femme fatal who leads Benny to his doom—remains open. How we are to read Benny—victim of primal urges he cannot control, monster, victim of external manipulation and scapegoat for crimes he has not really committed (facing certain conviction for his crimes, Benny hangs himself and finds himself back in the priestess’s body)—remains open. The book is simultaneously intriguing and disturbing. It is an exceptional achievement, refusing to offer pat or even palatable answers to the questions it raises. It could engender fruitful discussions about several different discussions, but students would need to be warned in advance about what they were being asked to read.