Non-Fiction Reviews

Review of Black Utopias: Speculative Life and the Music of Other Worlds

John Rieder

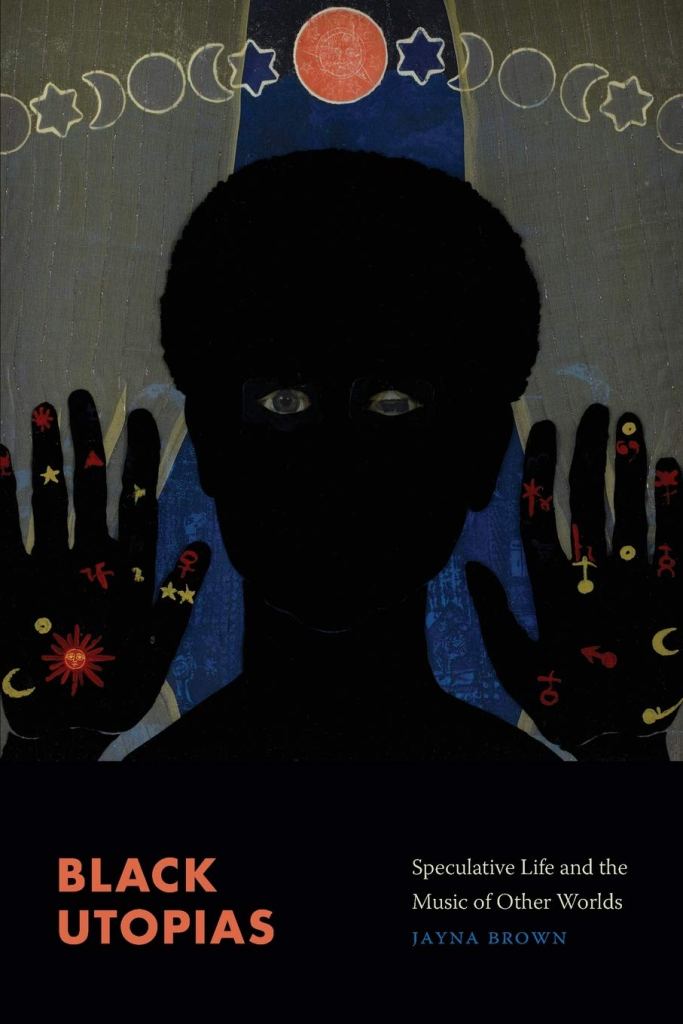

Jayna Brown. Black Utopias: Speculative Life and the Music of Other Worlds. Duke UP, 2021. Paperback. 224 pg. $25.95. ISBN 9781478011675. Ebook ISBN 9781478021230

Jayna Brown introduces her argument in Black Utopias with a short, moving section about her father, who was a poet, a Black Panther, a political exile, then a prisoner in the US, and finally, after his release, a self-proclaimed prophet in communication about the coming final days with a spirit named Golden Ray. Brown writes that struggling with what she considered her fatherʻs psychosis led her to ask questions about where one can draw the line betwen vision and madness. Perhaps, she wondered, one ought to listen more carefully to “mad souls.” The project of Black Utopias “is a way of residing in spaces of ambiguity” where the line between madness and prophetic vision cannot be confidently drawn (5). It is very worthwhile to follow her lead into exploring that uncanny space in this innovative, well-researched piece of scholarship.

Brown “use[s] the term utopia to signal the (im)possibilities for forms of subjectivity outside a recognizable ontological framework, and modes of existence conceived of in unfamiliar epistemes” (6). This is a very particular, narrow sense of what Lyman Tower Sargent, in one of the most widely cited essays in utopian studies, calls “the broad, general phenomenon of utopianism.” Sargent defines utopianism as “social dreaming—the dreams and nightmares that concern the ways in which groups of people arrange their lives and which usually envision a radically different society than the one in which the dreamers live” (Sargent 4). But the envisioning of radically different societies in, for example, the Back to Africa movement or Martin Luther Kingʻs non-violent protest, or implied by the critical dystopian features of Ralph Waldo Ellisonʻs Invisible Man (1952) or George Schuylerʻs Black No More (1931), are not part of the genealogy of black radicalism Brown constructs in this volume. Indeed the Harlem Renaissance is completely absent from Brownʻs essay, and Black nationalism is explicitly excluded from Brownʻs notion of utopianism because it seeks for recognition within the political and epistemological framework of white hegemony. Instead, says Brown, “the art and practices I consider involve a radical refusal of the terms by which selfhood and subjectivity are widely used and understood” (8). Brown wants to “redefine what the very term radical means” (26).

The version of radicalism that Brown delineates is indeed a stark departure from most received leftist, and especially Marxist, notions. She rejects dialectical thinking, which according to her remains inscribed within hierarchical practices that exclude black subjects from full participation in the category of the human. Nor are her radicals materialists in the scientific sense common to Enlightenment thought in general and most leftist critical theory in particular. Instead they embrace spiritualism and mysticism. Rather than rejecting life after death as an ideological soporific, they discover “radical forms of selfhood . . . produced in dream states, spirit, and temporal impulses not fettered by the cycle of life and death” (25). For the nineteenth century black woman preachers whose careers Brown describes, “The claim to life after death, while coded in the language of Christian belief, is a profoundly political claim by the living that they cannot ever truly be killed, enabling them to claim the space between life and death as another dimension of consciousness” (51). For jazz musician and poet Sun Ra, the subject of Brownʻs final chapter, civil rights activism was an illusory project because the only way to achieve peace and equality was to be dead. Therefore Ra often enjoined members of his audiences to “give up your death for me.”

The key category for Brownʻs redefinition of radicalism is the human. Her version of radicalism does not follow Marxist tradition or black nationalism in defining the goal of revolutionary activism as the seizure of state power, and it equally rejects civil rights protest’s goal of attaining equal treatment within the legal structure of state power. Brown’s radicals instead pursue something rooted in being itself, a sense of selfhood attainable only through “a complete break with time as we know it—an entirely new paradigm” (8). She argues that “black people’s existence is mythological in the first place. We don’t really exist, according the the logic of the human” (4). Readers familiar with the 1974 film Space Is the Place starring Sun Ra will surely hear echoes here of Raʻs film-opening declaration that time has officially ended, and of the speech Ra makes to a group of Oakland teenagers who challenge the outlandishly costumed musician whether he is for real. Ra replies: “I’m not real. I’m just like you. You don’t exist in this society. . . . I do not come to you as a reality; I come to you as a myth. Because that’s what black people are, myths.” What Brown adds to Raʻs position is an argument “that because black people have been excluded from the category human, we have a particular epistemic and ontological mobility” (7). There is “real power to be found in such an untethered state” because “those of us who are dislocated on the planet are perfectly positioned to break open the stubborn epistemological logics of human domination” (7). Brown accordingly places Sun Ra within a genealogy of black visionary radicalism that stretches back to the nineteenth century preachers Sojourner Truth, Rebecca Cox Jackson, Jarena Lee, and Zilpha Elaw, includes fellow mystic and jazz artist Alice Coltrane, and looks forward from them to the science fictional writing of Samuel R. Delany and Octavia E. Butler.

As the inclusion of preachers at one end of this history and writers of fiction at the other indicates, it is not music or any other sort of artistic form that unites these figures, but rather notions of the self and practices of community. It is the ritualistic, immersive character of Alice Coltraneʻs and Sun Raʻs performances that primarily attracts Brownʻs attention, rather than their innovations in the form of jazz (and both musicians could certainly afford rich material for a more formal approach). Brown says of Coltrane that her “mix of praise singing from the black Christian church, jazz, and Hindu worship songs” adds up to “a utopian practice of attunement with an infinite universe of aural vibratory phenomena” (60). Tellingly, Brown refers not to Coltraneʻs audience here but to her “congregation.” Brownʻs emphasis in the chapter on the four women preachers is less on any doctrinal position or rhetorical strategy than on their common investment and participation in alternative, non-heteronormative forms of community. Brown insists that the apolitical, otherworldly turn of the preachers and the musicians “also includes the concrete: the creation of community. Like Rebecca Cox Jacksonʻs Shaker community, Aliceʻs model could be considered escapist. But escape is an important trope in African American culture” (80). (Cf. Sun Ra: “If you find earth boring / Just the same old same thing / Come on and join us / At Outerspaceways Incorporated.”)

Brownʻs chapters on Octavia E. Butler and Samuel R. Delany are similarly focused on the way some of their fiction envisions forms of community. Her approach to Butlerʻs Parable series and Delanyʻs Triton (1976) shows little or no interest in literary devices such as plot or point of view or style. The focus in the Butler chapter is on the protagonist Olaminaʻs religious ideas for their own sake, not for the way they function within a literary fiction, and the same is mostly true for her attention to the setting of Delanyʻs Triton. For scholars of science fiction, perhaps the most pertinent aspect of her reading of Butler is her insistance, against what she calls a hagiographic tendency in Butler scholarship, on the “complexities and contradictions” introduced into Butlerʻs work “by a particularly grim version of Darwinism” that jostles uncomfortably alongside “biological forms of cooperation, symbiosis, and commensality” (84). For Brown, the utopian experiment that Olamina launches in the Parable novels remains heteronormative and deeply humanist—which are not, for Brown, good things. Finally, “the extent to which the texts can imagine evolutionary possibility is held back by a concept of change beholden to heteronormative ideas of a biological imperative” (107). Brownʻs argument has the considerable merit of emphasizing a set of issues within Butlerʻs work that is perhaps too often skirted or treated apologetically.

The pages Brown devotes to the nonfictional utopian writing of H. G. Wells are even more firmly set against critical evasion of what is problematic and disturbing in Wellsʻs writing. Brown argues that Wells “is revered as a foundational figure in science fiction while his frightening and horrific eugenicist ideas are ignored or minimized” (116). Within the structure of Brownʻs argument, Wells acts mostly as a foil to help introduce an analysis of the way Delany “explores the malleability of biological matter and frees it from normative determination” (127) in Babel-17 (1966) and The Einstein Intersection (1967). One of the main foci of Brownʻs reading of Delany is his treatment of desire, which, she says, Delany does not take in a Hegelian or Lacanian sense as something rooted in negation or lack, but rather in Deleuzean terms as “a productive and generative activity” (138). The point is the way this alters conceptions of the subject and the dependence of subject formation on relationality. This is the place in Brownʻs argument that relies most strongly and productively on queer theory, asserting that “transgender and transsexuality theories” show the way to “relaxation of the need for set and fixed gender and sexual identities and the embrace of fluid and expansive modes of being” (138).

Brownʻs final chapter is devoted to the person who seems to me to preside over the entire argument, Sun Ra. True to her approach to Butler, Brown avoids turning her analysis into a hagiography, facing squarely up to the authoritarianism of Raʻs band leadership. But she is more interested—and rightly so—in the way that “the homosocial space of the Ra houses was not modeled on that of a heterosexual family or compound of families. While they were based in discipline, they were not based in hierarchical rank or competition” (162). This kind of noncompetitive, nonmasculinist organization of the jazz orchestra runs counter to dominant practices of the music then and now, but for Brown it is more important that it is based on challenging the notion of the possessive individual and all that comes with it. In her reading of Sun Ra, Brown achieves the clearest enunciation of her profoundly non-Althusserian version of antihumanism. “For Ra,” she says, “being human is a state of ignorance and not a status we should be fighting for. . . . Black people have to let go of the idea of the human, which Ra sees as inseparable from the liberal terms that have defined it. . . . Raʻs call is not for a new genre of the human but a new genre of existence” (172-73).

Whether Brownʻs intervention into utopianism, black intellectual history, and the genealogy and significance of Afrofuturism will end up being judged boldly iconoclastic or merely interestingly idiosyncratic I do not presume to be able to say. But I can say with absolute certainty that I learned a lot from this book, and that I found it a fascinating and pleasurable read.

WORKS CITED

Sargent, Lyman Tower. “The Three Faces of Utopia Revisitied.” Utopian Studies, Vol. 5, No. 1 (1994), pp. 1-37.

John Rieder, an emeritus professor of English at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, was the recipient of the SFRA Innovative Research Award in 2011 and the SFRA Lifetime Achievement Award in 2019. He is the author of Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction (Wesleyan UP, 2008), Science Fiction and the Mass Cultural Genre System (Wesleyan UP, 2017), and Speculative Epistemologies: An Eccentric Account of SF from the 1960s to the Present (Liverpool UP, 2021). He has served on the editorial board of Extrapolation since 2010.