Symposium: The CyberPunk Culture Conference

Pants Scientists and Bona Fide Cyber Ninjas: Tracing the Poetics of Cyberpunk Menswear

Esko Suoranta

A translucent plastic raincoat on the streets of a futuristic Los Angeles. A long leather jacket, swinging into an austere foyer just before a gunfight. Mirrorshades. Spiky hair, colored neon green. Chrome. The tropes of cyberpunk fashion are well established, and it is easy to see how the mode’s general aesthetic has always influenced and been influenced by personal expression in various subcultures through clothing and accessories. The tokens of anarchist self-images, like piercings and leather clothes, readily lent themselves for cyberpunk at its inception as a new movement in SF, where a dystopian, unevenly distributed future would be played out not on spaceships or distant planets but in the urban realm, the streets of the sprawl, the megalopolis. For that struggle, the cyberpunk (anti-)hero needed the clothes to boot.

In this paper, based on my presentation at the Cyberpunk Culture 2020 conference, I provide a sporadic tour of men’s fashion in cyberpunk art, from literature to film to games, and read it in relation to examples of real-life cyberpunk-inspired menswear. I argue, somewhat uncontroversially, that changes in dress as part of a mode’s poetics reflect changes in its politics over time and between works. I focus on menswear, rather than cyberpunk fashion in general, in the interest of uncovering a specifically male-coded, and cis-heteronormative, relationship with fashion: as I hope will become clear, much of cyberpunk-influenced menswear justifies itself with function and utility as if such features were necessary for men to participate in fashion movements. I detect a change from the lone-wolf outlaws of original cyberpunk to militarized super-hero enforcers of the current mainstream, but also present a counterpoint to both in the guise of the cool, gray cyberpunk man: a “pants science” enthusiast who combines the fantasies of individualism and a low-key presentation to the hidden, almost science-fictional, functionalities of his clothing.

These three figures emerge as male cyberpunk archetypes with their distinct looks and politics with counterparts both in fiction and on the streets today. Where the original cyberpunk man wanted his aesthetic to scream counter-culture and opposition to “the man” of Reagan’s United States, the futuristic cyber-superhero needs form and function to aid him in militarized quests on mean, dystopian streets. Finally, the contemporary, unobtrusive cyberpunk wants his outfits to be techwear of the highest quality, but without drawing too much attention to himself. As such, all three point toward what Stina Attebery calls “fashion [as] a speculative practice: a future-oriented, constantly shifting set of speculative assumptions about the future of social expression and posthuman embodiment” (“Chrome and Matte Black,” see also “Fashion” in The Routledge Companion to Cyberpunk Culture). Cyberpunk menswear experiments with expanding the scope of masculine self-expression and does in ways that can be both problematic and emancipatory, as I hope becomes clear from the examples addressed below.

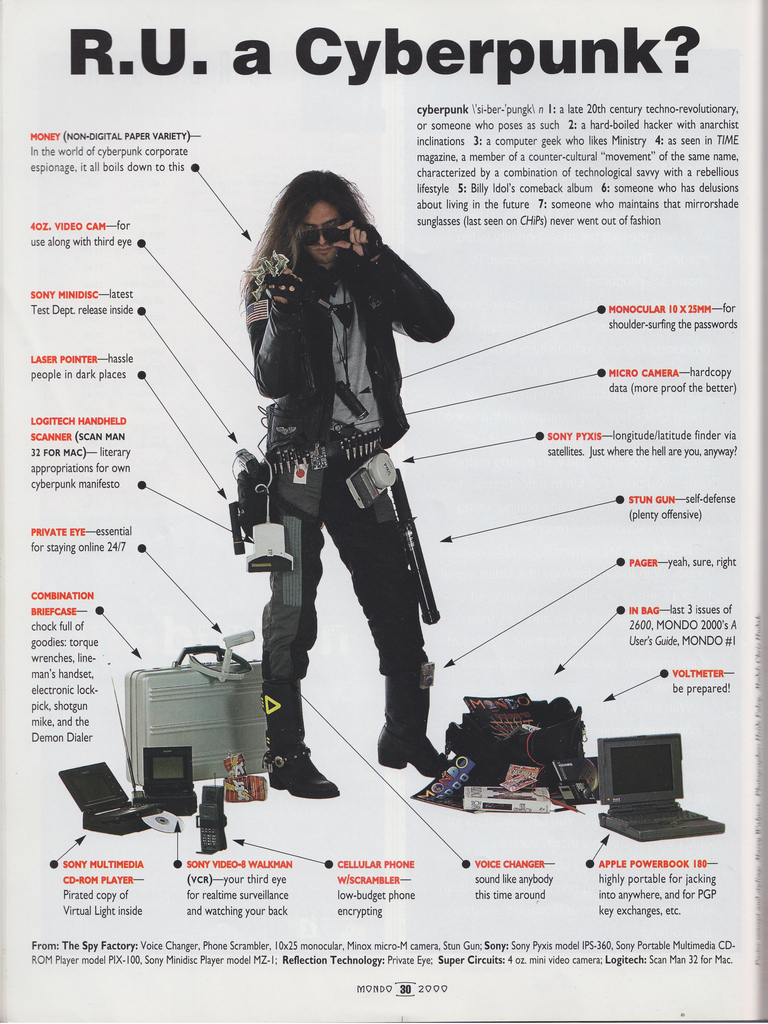

To get started, let us consider a spoof image from Mondo 2000, the cyberpunk culture magazine (figure 1.). With the tongue-in-cheek query “R.U. a Cyberpunk” it showcases many of the features of classic cyberpunk menswear, providing an itemized list of what a stereotypical cyberpunk should have in his inventory from spy equipment to 1990s computer paraphernalia and media devices. The model is clad in all-black-everything, wears heeled leather boots and a pilot jacket, but notably the items of clothing are not on the numbered list of essential gear. They are to be read as incidental details, as self-evident, but they naturally betray the debt cyberpunk owes to punk and heavy metal cultures. In addition, the clothes ossify the look of a cyberpunk beyond his gadgets.

Despite being a parody image, the figure of the model is aspirational: standing out and standing up against abstract control and oppression is possible if one projects an in-your-face attitude, possesses everything in gadgetry the early 1990s have to offer, and makes that clear to everyone who dares look into the cold reflection of mirrored shades.

Importantly, the shades are the one exception where a fashion accessory is marked as part of the cyberpunk’s essential gear. They are mentioned in entry number seven, where one meaning of “cyberpunk” is given as “someone who maintains mirrorshades never went out of fashion.” It is indeed mirrored sunglasses to which the bad-ass counterculture ethos of cyberpunk fashion can be traced. Their significance is summarized by Bruce Sterling in his preface to the Mirrorshades (1986) anthology of cyberpunk stories: “By hiding the eyes, mirrorshades prevent the forces of normalcy from realizing that one is crazed and possibly dangerous. They are the symbol of the sunstaring visionary, the biker, the rocker, the policeman, and similar outlaws” (38). It is clear in retrospect that Sterling should have problematized this vision of visionaries outside the law as history keeps revealing how the lone rebel is rarely a force for progress or good, but the visionary individual against the “forces of normalcy” is central to the popular understanding of the cyberpunk hero. To look like a cyberpunk is to tell onlookers that one is a misfit, a potential threat to the status quo.

One later example emerges in The Matrix (1999), arguably the most successful cyberpunk movie to date. The outlaws of Nebuchadnessar face a force of totalizing normalcy, as machines seek to keep humanity lulled in virtual battery-acid dreams. The thematic resonance of the mirrorshades is clear in figure 2. Neo, making his choice between the red and blue pill, sees his possible futures and potential reflected back at him from the outlaw guru Morpheus’s lenses. As such, the Stoic, mysterious, black-clad counterculture man with shades to hide his dangerousness remains a cyberpunk archetype.

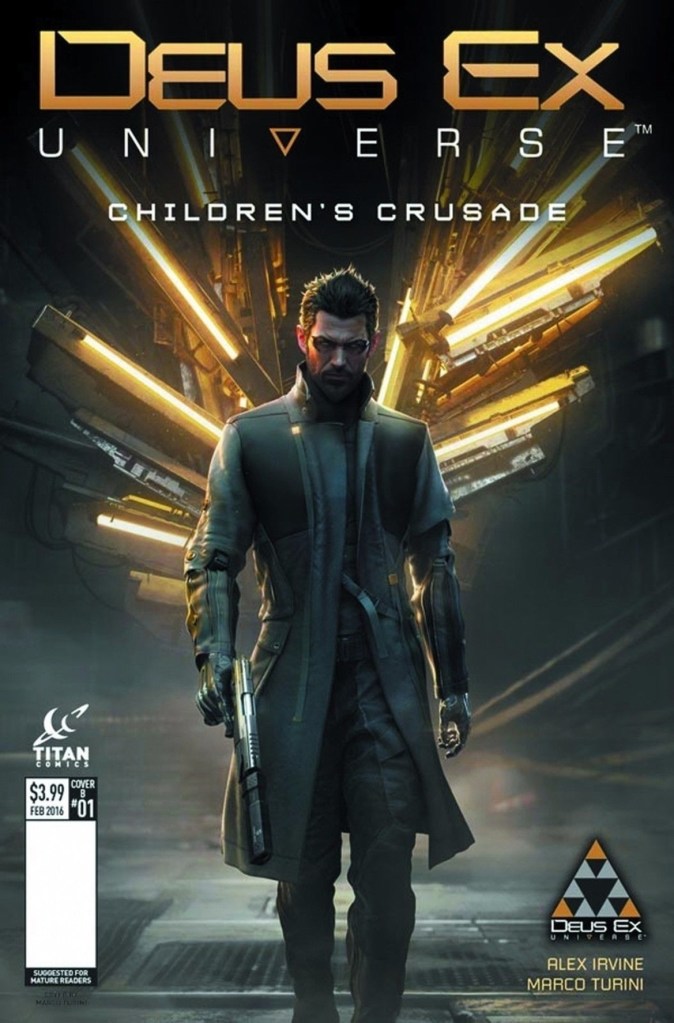

It is no surprise that the fringe-character Sterling describes, and, in a sense, Morpheus epitomizes is easy to co-opt for militant power-fantasies. Adam Jensen, the hero of the Deus Ex franchise of games and related products, is a case in point (figure 3.). Starting out as a security officer, he is ripped apart by explosions and gunfire and fitted with a fully cybernetic body by his employer Sarif Industries, becoming a RoboCop with free will in a dystopian near future. In the games of the franchise, he works for Sarif Inudstries, gray-ops counter-terrorism units, and seeks to uncover actions of the Illuminati. His cybernetic augmentations allow him to see and punch through walls, employ hyper-reflexes, blades in his forearms, and invisibility, making him a Swiss-army-cyber-knife with only the most dangerous villains able to oppose him. Jensen is thus the cyberpunk as superhero, a vigilante fighting against terrorism with his incredible augmentations. He is part of the militarized world of enforcers, embodying extra-legal justice and distributing it through degrees of violence (it is possible to complete the games almost completely without killing, but Jensen still remains very much embedded in networks of violence).

In such a line of work, clothing and a functional style are essential. Jensen has sunglass implants in the style of William Gibson’s Molly Millions from Neuromancer (1984), he speaks with a low growl, and wears a long dark coat worthy of any character from The Matrix. His trench-coat is adapted to stay out his way: his sleeves retract to make room for hand-cannons and arm-blades and the design is no haphazard accident. The launch trailer for Deus Ex: Mankind Divided (2016) shows, in a sequence lasting some two seconds, that Jensen has an ACRONYM coat (figure 4.). ACRONYM is a real urban techwear brand, based in Berlin, expensive, and aiming for the highest degree of functionality possible for clothing. Its founder and head designer Errolson Hugh (figure 5.) appears at times almost indistinguishable from cybersuperhero Jensen.

Speaking of the design process for Jensen’s coat for Gameinformer, Hugh said ACRONYM approached the project like any other, asking who is using the garment, for what purposes, and what specific challenges they might encounter (Cork). Focusing on function is a departure from the more detached aesthetic of mirrorshades and leather in classic cyberpunk discussed above. Jacked into the matrix, one’s success is not dependent on what one wears, and virtual avatars can look like anything at all. Meatspace is thus always secondary to cyberspace and the leather-clad look mainly transfers a counter-cultural message rather than responds to functional needs. For the futuristic cyberninja, like Jensen, however, the street is his primary haunt and fashion choices must reflect that.

The ultra-functional cyberpunk like Adam Jensen remains, for most intents and purposes, a fictional character, but the influence of the archetype leaks into the everyday. It should not come as a surprise, then, to find William Gibson and Errolson Hugh side by side in near-identical outfits (figure 6). Gibson is a self-proclaimed ACRONYM fan and his fiction from Pattern Recognition (2003) onward is laden with the author’s fascination with brands, fashion, and techwear. The novel even prompted Buzz Rickson’s to launch a product line in his name, inspired by a fictional jacket of theirs appearing in it (figure 7.). In an interview for The Guardian’s “The look I love” column, Gibson wore an outfit comprised entirely of ACRONYM clothes. In the headline, he is quoted saying that he is always striving not to be noticed (Marriot). The statement follows one Gibson made for the lifestyle site Heddel’s, citing “gray man theory” as one inspiration for his choices in clothing. According to the theory, allegedly from the security industry, dressing in unremarkable clothes, like chinos, is a must for security personnel as anyone with combat pants will be shot first in any hostile encounter (Shuck).

Deb Chacra, professor of engineering at Olin College, makes a connection between Gibson’s attempt to remain unnoticed and the so-called Great Male Renunciation of late 18th-century Europe, during which flamboyant designs and bright colors stopped being features of men’s clothing (“Metafoundry 30”). The image of the dandy born then, seemingly uninterested in self-decoration and hence invested to black and white in his outfits, continues to inform much of men’s fashion even to a fault. Gray cyberpunk men can be seen as contemporary takes on the dandy ethos: Beau Brummel, the chief architect of the Great Male Renunciation, and Gibson both wear outfits that appear unmarked, but are never coincidental.

The continuum from Adam Jensen to Errolson Hugh to William Gibson shows the paring down of the cyberninja outfit to the more quotidian streets of today. While the classic leather-clad cyberpunk screams counterculture with his fashion choices and Adam Jensen needs his retractable function-sleeves to blast future terrorists, the gray cyberpunk man remains unobtrusive, but knows in his heart of hearts that he is donning the most functional, technical, and exclusive gear known to mankind.

To illustrate this further, let us take a look at some brand-writing from the Brooklyn-based clothing company Outlier. Consider the following quotes and figure 8.:

Ultrafine Merino T-Shirt

A near perfect t-shirt made with a Mackenzie 17.5 micron Merino Jersey, nature’s finest performance fabric. Beautifully soft and remarkably dry to the touch, merino’s hygroscopic properties help cool you in the heat and insulate you in the cool.

Injected Linen Blazer

An unlined blazer that wears like air. The Injected Linen fabric combines industrial warp-knit weft-insertion techniques with natural linen to create a material that is incredibly open and breathable while holding an elegant opacity.

To me, that is the sound of science fiction and, more precisely, the poetics of estrangement applied to clothing. Outlier garments give a very ordinary impression and they are without visible logos or texts that would reveal their brand identity, but they are described so as to make them unique and strange, to have consumers know there is more than meets the eye. They thus combine the cyber-ninja ethos of functionality, hidden in patterns and materials, to the gray man aesthetic of unobtrusiveness.

There is a connection to be made between the Outlier product descriptions and Gibson’s Bigend trilogy of contemporary novels. Specifically, the poetics of Outlier can be read as what Jaak Tomberg calls the “double vision of SF” where text registers as realism and science fiction not side by side or a passage after the other, but at the same time, “both plausibly everyday and plausibly cognitively estranging” (263). Tomberg’s principal example is the following description of protagonist Cayce Pollard’s outfit in Pattern Recognition:

[…] for the meeting, reflected in the window of a Soho specialist in mod paraphernalia, are a Fresh Fruit T-shirt, her black Buzz Rickson’s MA-1, anonymous black skirt from a Tulsa thrift, the black leggings she’d worn for Pilates, black Harajuku schoolgirl shoes. Her purse-analog is an envelope of black East German laminate, purchased on eBay—if not actual Stasi-issue then well in the ballpark.

8

In addition to the information-laden nominalization of articles of clothing, it should be noted that Cayce shares in the novel Gibson’s attempts to be unnoticed, clipping logos and other brand-markers off her clothes, favoring black, simple garments. As a result, she emerges as the fictional counterpart to the cool, gray man in favor of Outlier. Lee Konstantinou discusses her as an archetypal cool character (Cool Characters 240–269) and finds in Pattern Recognition’s “coolhunting aesthetics” an attempt to “reconnect the free-floating brand to the hidden supply chains that make brands profitable in the first place” (“The Brand as a Cognitive Map” 95). As such, Cayce appears as a central inspiration for the gray cyberpunk man aesthetic (and it should be noted that much of what she wears can be construed as gender-neutral). Both are less interested in instant recognition of the excellence of their garments through brand semiotics, but rather in an insider knowledge of fabrics, technologies, and details of production.

The science-fictional poetics of a brand like Outlier coincide with the latest developments in cyberpunk literature that is not all too keen to focus on superheroes like Adam Jensen, but rather concerns itself with more naturalistic struggles under accelerating digital capitalism – a theme I deal with in my dissertation in preparation. Such fiction questions the possibility of fighting and winning against the powers that be, showing that, under contemporary capitalism, different means of resistance than those of the superhero vigilante are needed (for examples of analyses pointing to this direction, see Suoranta 2014 and 2020). The realization that transhumanist augmentation or the vigilantism of loners does not guarantee progress or resilience of any kind can be seen in the fairly toned-down characters of authors like Malka Older, Annalee Newitz, and Tim Maughan, among others.

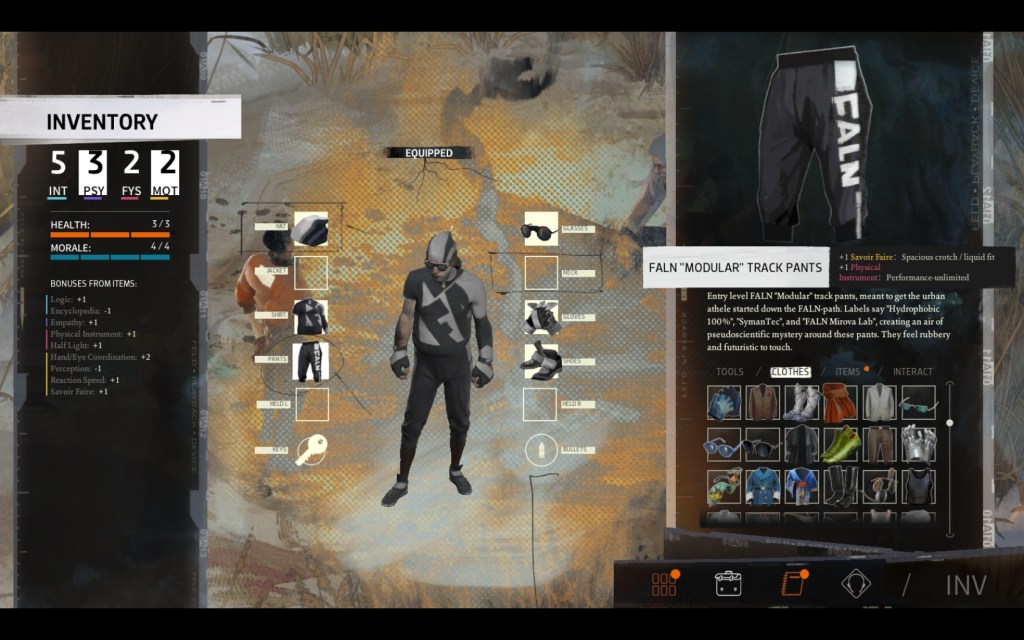

To conclude, I want to point out how the techwear enthusiast who is into brands like ACRONYM or Outlier has already reached the archetypal, stock-figure status of the mirrorshaded hacker, emerging as an object of parody, specifically in the 2019 CRPG Disco Elysium. Here is an exchange between Cuno, a street kid, and the amnesiac cop protagonist. Consider the following, keeping the Outlier blurbs in mind:

“YOU — ‘Alright, entertain me — what’s so great about these pants?’

CUNO — ‘Pig, these are FALN *Modulars*! Liquid fit, performance crotch, urban survival shit! Made in Mirova… by scientists. *Pants* scientists.

‘Believe it, you *need* this shit…’ He unzips his jacket to give you a quick peek at the plastic-wrapped pants. They are graphite-black and look brand new.’’

In Disco Elysium, players can naturally collect a whole FALN outfit in the course of the game, ironically role-playing the pants scientist aficionado, functioning optimally in his tactical urban environment with the clothes giving various bonuses and penalties to different skills. In fact, the skills of the player-character comment what goes on in the game as various inner voices, provided the relevant skill checks are successful:

SAVOIR FAIRE [Trivial: Success] — These could drastically improve your chances of survival in the urban wilderness.

PHYSICAL INSTRUMENT [Easy: Success] — Coach Physical Instrument endorses these pants. […]

CONCEPTUALIZATION [Medium: Success] — They will also make you look like an idiot.

The FALN aesthetic hinges on as-visible-as-possible branding on the products themselves and the designs hark to ACRONYM’s futuristic gear (figure 9.). At the same time, the language of “pants science” aligns them with Outlier’s SF poetics. Teenage Cuno’s enthusiasm and Conceptualization’s judgment take a gentle piss out of the speculative promises cyberpunk menswear can be seen to make. They let slip that, in fact, leather jackets do not make one a visionary, ACRONYM performance clothes do not make one a superhero, and wearing the results of Outlier’s pants science does not make a man special. Or further, whatever aesthetic or functional effects these clothes might endow one with, they are easily overshadowed by disproportionate hype or aggrandizement. Still, like Attebery points out, the expression they afford does the speculative work of fashion, hinged on cyberpunk ideas.

I hope this smörgåsbord of pants, coats, and people real and fictional has shown that cyberpunk menswear flows in and out of fiction in various interesting ways and that its changing poetics are connected to the mode’s politics over time and between works in different media. My examples chart a shift from Sterling’s visionary outlaws to superhero fashionistas, and, finally, to the toned-down protagonists of contemporary cyberpunk literature and, in a natural dynamic, their parodies. Further explorations could be done with the help of the impressively curated Cyberpunk Clothing wiki on Reddit, where the brands featured here appear alongside suits, cybergoth wear, milspec, and high fashion. In a sense, the wiki appears as a similar contemporary inventory of essentials as the Mondo 2000 parody image we started with, this time for the expanded, contemporary world of cyberpunk that we inhabit, for better and worse. As with all aesthetic choices, cyberpunk fashion also engenders both toxic and wholesome politics from militarized looks that border on fascist insignia to unobtrusive normcore ideals home at a cozy startup. Both designers and consumers employ its semiotics and design ideals to strive toward the various potentials of expression associated with cyberpunk. It thus appears clear that of all science-fictional modes, cyberpunk is well on its way of influencing fashion and aesthetics.

WORKS CITED

Attebery, Stina. “Chrome and Matte Black: Cyberpunk’s Speculative Posthuman Fashions.” Cyberpunk Culture 2020, 10 July 2020, Virtual Conference. Conference Presentation. cyberpunkculture.com/cpcc20/program-friday/%C2%A732-stina-attebery/. Accessed 5 Nov. 2020.

Cork, Jeff. “Haute Future: How Fashion Designers Improved Deus Ex.” Gameinformer, 24 Apr. 2015. http://www.gameinformer.com/b/features/archive/2015/04/24/haute-future-how-fashion-designers-improved-adam-jensen-s-deus-ex-coat.aspx. Accessed 5 Nov. 2020.

Chachra, Deb. “Metafoundry 30: Confusion Matrices.” 29 March 2015. tinyletter.com/metafoundry/letters/metafoundry-30-confusion-matrices. Accessed 29 Oct. 2020.

“Cyberpunk Clothing.” Reddit Inc, 27 May 2008, http://www.reddit.com/r/Cyberpunk/wiki/clothing. Accessed 29 Oct. 2020.

“Deus Ex: Mankind Divided – Announcement Trailer PS 4.” YouTube, uploaded by Playstation, 8 April 2015, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uvSs5b6y-YM.

Disco Elysium. Written by Robert Kurvitz, ZA/UM, 2019.

@ersln. “THE MOST KNOWN UNKNOWN™ … ΛCRИM … J1A-GT … Now … https://acrnm.com/products/J1A-GT_NA #acrnm.” Twitter, 13 Dec. 2015, 3:42 a.m., twitter.com/erlsn/status/675853241482129408. Accessed 9 Nov. 2020.

@ersln. “Uncle Bill. https://instagram.com/p/BQ6ydbyldrR/.” Twitter, 25 Feb. 2017, 7:45 p.m., twitter.com/erlsn/status/835546317065707523. Accessed 9 Nov. 2020.

Gibson, William. Pattern Recognition. Viking, 2003.

“Buzz Rickson William Gibson MA-1 Flying Jacket, Tailored Cut.” History Preservation Associates, 2000, http://historypreser-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/ma1_wg_slim_mont.jpeg. Accessed 9 Nov. 2020.

Konstantinou, Lee. “The Brand as a Cognitive Map in William Gibson’s Pattern Recognition.” boundary 2, vol. 36, no. 2, 2009, pp. 67–97.

Konstantinou, Lee. Cool Characters: Irony and American Fiction. Harvard University Press, 2016.

Luo, Jiaqi. “Why Is Post-COVID China Embracing a Cyberpunk Aesthetic?” Jing Daily, 7 Oct. 2020, https://jingdaily.com/china-luxury-trends-cyberpunk-covid-louis-vuitton/. Accessed 6 Nov. 2020.

Marriot, Hannah. “William Gibson: ‘I’m always striving not to be noticed.’” The Guardian, 16 June 2020, http://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2020/jun/16/william-gibson-im-always-striving-not-to-be-noticed. Accessed 5 Nov. 2020.

Outlier Incorporated. OUTLIER Simple Innovation and Wild Experimentation in Clothing, 2008, outlier.nyc. Accessed 9 Nov. 2020.

Shuck, David. “William Gibson Interview: His Buzz Rickson Line, Tech Wear, and the Limits of Authenticity.” Heddel’s, 5 March 2015, http://www.heddels.com/2015/03/william-gibson-interview-buzz-rickson-line-tech-wear-limits-authenticity/. Accessed 5 Nov. 2020.

Sirius, R. U. “R.U. a Cyberpunk? Well? R.U? … Punk.” Mondo 2000, 30 Aug. 2017, http://www.mondo2000.com/2017/08/30/r-u-a-cyberpunk-well-r-u-punk/. Accessed 5 Nov. 2020.

Sterling, Bruce. “Preface to Mirrorshades.” Science Fiction Criticism, edited by Rob Latham, Bloomsbury, 2017, 37–42.

Suoranta, Esko. “Agents or Pawns? Power Relations in William Gibson’s Bigend Trilogy.” Fafnir – Nordic Journal of Science Fiction and Fantasy Research vol. 1, no. 1, 2014, 19–31.

Suoranta, Esko. “An Ever-Compromised Utopia: Virtual Reality in Thomas Pynchon’s Bleeding Edge.” New Perspectives on Dystopian Fiction in Literature and Other Media, edited by Saija Isomaa, Jyrki Korpua, and Jouni Teittinen, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2020, 101–18.

The Matrix. Directed by Lana Wachowski and Lilly Wachowski, Warner Brothers, 1999.

Tomberg, Jaak. “On the ‘Double Vision’ of Realism and SF Estrangement in William Gibson’s Bigend Trilogy.” Science Fiction Studies vol. 40, no. 2, 2013, 263–85.Verhaaf, Michaël. Deus Ex Universe: Children’s Crusade #1 Game Cover. 2016.