Nonfiction Reviews

Review of Rendezvous with Arthur C. Clarke: Centenary Essays

Jerome Winter

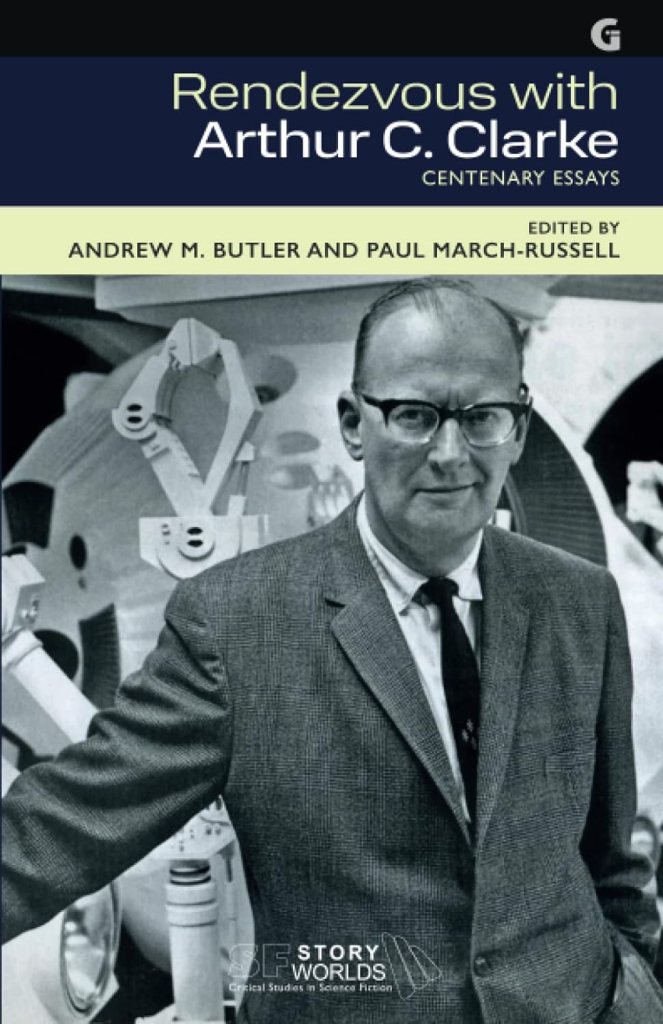

Andrew M. Butler and Paul March-Russell, eds. Rendezvous with Arthur C. Clarke: Centenary Essays. Gylphi Limited, 2022. SF Storyworlds: Critical Studies in Science Fiction Series. Paperback. 306 pg. $40.00. ISBN 9781780241081.

Andrew M. Butler and Paul March-Russell, the editors of this new collection by leading scholars of Arthur C. Clarke, begin with a riposte to the still pervasive marginalization of genre work in literary studies and culture at large. In a 1998 article for The Village Voice, Jonathan Lethem, a supremely genre-savvy writer, famously offered a broadside in which he characterized Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendezvous with Rama as “reactionary SF as artistically dire as it was comfortingly familiar” (qtd. in Butler and Russell 1). If Rendezvous with Rama had lost its Nebula Award to Thomas Pynchon’s also-nominated Gravity’s Rainbow in 1973,Lethem facetiously conjectures that, then, the New Wave experiments of the SF genre would have at last escaped their commercial straitjackets, and the SF genre as a basic category of fiction would have evaporated with a collective sigh of “good riddance.”

Butler and March-Russell bristle at Lethem’s tendentious dismissal of Clarke’s brand of hard-SF fiction, but, more substantively, they challenge the equally unquestioned conventional binary that seeks to oppose a virtuosic genre-hybridizing and postmodern writer such as Thomas Pynchon to a less flamboyant innovator like Arthur C. Clarke who wrote, at least superficially, from within genre constraints. Indeed, with this impressively informed and diverse collection of essays that began at a 2017 centenary conference memorializing Clarke’s birth in 1917, Butler and March-Russell make a convincing case that the broad range and intricate subtlety of Clarke’s deep veins of literary-SF ore have yet to be critically assayed, let alone sufficiently mined. In their introduction, Butler and March-Russell argue that it is impossible not to read Clarke as a “homo duplex, a perpetually two-sided and enigmatic figure” (7). Indeed, the deeper and more carefully a reader looks, the more the lucid simplicity of Clarke’s career concerns seems to be, on closer reflection, a mysterious bundle of contradictions.

One of the overlooked ways in which Pynchon and Clarke are surprisingly likeminded is their obsession with fictively overcoming the inexorable laws of physics, such as gravity or entropy. Noting that the Overlords in Childhood’s End (1953) both fly and manipulate gravity, Thore Bjørnvig traces Clarke’s literary pedigree to the long tradition of eschatological and apocalyptic writing that levitates the future of humanity upward to disruptive visions of radical progress. Jim Clarke then picks up this fundamental paradox of Clarke’s rational-fantastic fiction to explore Clarke’s debt to what Clarke himself called his own unique blend of “crypto-Buddhist” metaphysics. Likewise, in “Clarkaeology,” Patrick Parrinder argues that even though Clarke’s fiction seems to be “strikingly forward-looking” (35), it also evinces a powerful sense of “belatedness,” betraying a keen interest in archeological theories about the diffusion of cultures, especially in the fascination with megaliths and obelisks.

Developing this critical analysis of Clarke’s unique twists on future histories, co-editor Paul March-Russell, in his own contribution to the collection, performs a close reading of The City and the Stars (1956) to argue that Lee Edelman’s notion of queer futurity can help readers understand how Clarke subtly subverts the common assumption that this prototypically hard-SF writer implicitly champions technological and imperial (galactic) progress. Similarly, connecting Clarke to Robert Heinlein’s movie tie-in Destination Moon (1950), the Russian SF writer Pavel Klushantsev, and the British SF writer E.C. Tubb, Andy Sawyer’s chapter argues that Clarke avoids straightforward propagandizing for Cold War ideology. Sawyer, though, cautions that Clarke wrote for an audience composed largely of technocrats and fans, and Clarke therefore soberly appeals to the power of scientific explanations and regularly evokes the sublimity of the cosmos, even if he also undercuts these semi-heroic gestures.

Another chapter that concerns itself with excavating the queerness in Clarke’s oeuvre would be Mike Stack’s “Clarke Dare Speak Not Its Name,” which explores the futuristic normative bisexuality of Imperial Earth (1975) against the illuminating historical backdrop of the partial decriminalization of homosexuality in the UK. In an essay that is equally attentive to textual details, co-editor Andrew Butler, drawing on theories of Freud, Heidegger, Haraway, and Derrida, explicates Clarke’s representations of tools in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and 2010: Odyssey Two (1982)as not only empowering prosthetic enhancements but also as unsettling posthuman transformations. With an emphasis on Clarke’s uncertain mixture of skeptical deflation and heady enthusiasm entirely in keeping with this nuanced volume, Helen M. Rozwadowski discusses Clarke’s writings and life of active undersea diving to show how Clarke probes the limits the frontier analogy for both sea and space.

This collection also incisively focuses on Clarke’s legacy with one chapter by Lyu Guangzhao on Clarke’s influence on Liu Cixin and contemporary Chinese SF, and one chapter by Joseph S. Norman on Clarke’s influence on Iain M. Banks and New Space Opera. Nick Hubble’s final chapter on the history of the Clarke Award and how the award has become more controversially unpredictable and less narrowly restrictive in its selective criteria over the years suggests the more or less consensus view today, in China Mieville’s clever pronouncement, that “any sufficiently advanced science fiction is indistinguishable from literature” (qtd. in Hubble 236). This chapter is a fitting conclusion to the volume as it revisits the dismantling of the problematic binary between SF and mimetic literature that the other important contributions to Clarke scholarship contained in this collection also consistently upend. This wide-ranging, insightful, and often scrupulously evenhanded collection would serve equally well SF novitiates, veteran Clarke scholars, and those interested more broadly in the contested boundaries between genre and mainstream fiction.

Jerome Winter is an SF scholar who studies literary space opera, citizen science, and pedagogy. His most recent published book is a critical introduction to the Mass Effect videogame series as an innovative iteration of space-opera narrative.