Media Reviews

Review of Starship Troopers: Extermination

Drew Adan

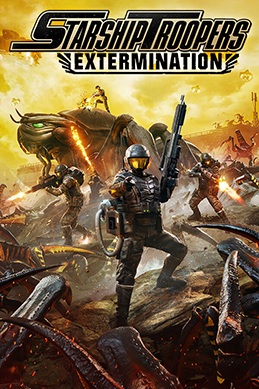

Starship Troopers: Extermination. Offworld Industries, 2024.

Starship Troopers: Extermination is a 2024 first person extraction shooter developed by Canadian studio Offworld Industries. An official entry in the Starship Troopers franchise, the game sees players assume the role of soldiers in the Mobile Infantry battling an insectoid, hostile alien species known as the Arachnids or “Bugs” across a series of planets. While based on Robert A. Heinlein’s 1959 novel, the game is set in the universe of the 1997 Paul Verhoeven film and adopts a similar jingoistic, satirical tone. While offering fleeting moments of fun, frenetic gameplay, Starship Troopers: Extermination largely misses its target as it fails to deliver on the rich world building of its source material or offer a compelling gameplay loop to keep players coming back for more.

As of January 2025, Starship Troopers: Extermination offers two gameplay modes. The first is a brief, single-player campaign across 25 missions that place the player in the boots of an elite special operations squad of the Mobile Infantry. These missions are narrated by the voice of Casper Van Dien who reprised his role as Juan “Johnny” Rico, the protagonist of Verhoeven’s 1997 cult classic sci-fi action film. These missions see the player and three NPC (non-player characters) squadmates traversing bland subterranean and planetary surface environments to complete singular, simplistic objectives such as eliminate specific enemies or hold key areas. There is little to no character development of these squadmates who only offer brief and banal exclamations. Before each mission, a static rendering of General Rico briefs the player on the upcoming mission with monologues that offer little narrative development or meaningful additions to the Starship Troopers cannon. These missions could have been strengthened in both narrative and gameplay if multiple objectives were combined into longer missions. This would provide an experience closer to a proper single-player campaign than an extended tutorial.

The other game mode, and the most compelling experience Starship Troopers: Extermination offers, is a cooperative, 16-player PvE (player versus environment) mission-based extraction shooter. Before the mission, players choose one of six trooper classes, each with their own weapon, equipment, and ability loadouts. So far, the six classes included in the base game are Sniper, Demolisher, Guardian, Engineer, Medic, and Ranger. Each mission starts with players deploying from a dropship and completing various objectives which typically culminate in tower-defense style gameplay as players collaboratively spend mission specific currency to build base fortifications, turrets, and ammo caches. After the base is successfully defended, players must make a hurried rush to the extraction point to complete the mission. This extraction sequence is one of the most engaging parts of the game as persistent enemy corpses litter the battlefield and transform the planet surface into a labyrinthian hellscape of explosions and green Arachnid blood. This leads to some truly cinematic moments as frenetic gameplay combines with visual spectacle and desperate cries from fellow squad members.

Unfortunately, Arachnids are not the only bugs one must battle while playing Starship Troopers: Extermination. Various technical issues have plagued the title through early access and 1.0 release. Performance issues persist on consoles and higher-end PC hardware as swarms of enemies on screen see frame rates plummeting. Hard crashes are frequent and odd textures or visual glitches are rampant. These issues contribute to a sense of Starship Troopers: Extermination being an underdeveloped project attempting to cash in on franchise affiliation. In 2022 players created a mod for Squad (also developed by Offworld Industries) called Squad Troopers. This mod introduced PvE gameplay and Starship Troopers skins for the Squad engine, gameplay, and weapons. It was well received by players, becoming one of the most popular and well-reviewed mods in the Squad community (Steam). It appears that Offworld Industries ran with this concept in their development of Starship Troopers: Extermination.

Starship Troopers: Extermination had the great misfortune of releasing the same year as another wildly popular squad-based, cooperative bug shooter inspired by the Starship Troopers universe. Arrowhead Studio’s Helldivers 2 was a massive and surprise hit for publisher Sony, breaking sales records and overwhelming game servers shortly after its release. In many ways, Helldivers 2 succeeds where Starship Troopers: Extermination fails as it actualizes a compelling game world and supportive community immersed in roleplaying dispensable “divers” who are fighting to spread “managed democracy” across the galaxy. Despite not having the rich lore of a storied franchise to draw on like Starship Troopers or Warhammer 40,000, Helldivers 2 offers players the opportunity to explore various worlds with scattered tidbits of environmental storytelling, and participate in a live service Galactic War moderated by dungeon master “Joel” who controls enemy tactics, in-game events, and the game’s metanarrative. The community has enthusiastically embraced the heavy-handed, tongue-in-cheek satire of Helldivers 2 producing videos, fan art, and other content that mimics the fascistic and jingoistic tone of in-game propaganda.

However, such satirical treatment of fascism, colonialism, and militarism as seen in Starship Troopers: Extermination and Helldivers 2 has created an online discourse around the public’s ability to differentiate satire from genuine endorsement (Rosenblatt). Even the richest man in the world, Elon Musk, was mocked for seemingly missing the satirical message of the Starship Troopers film (Greg). This disheartening lack of media literacy calls into question the efficacy of satire in video games for the purposes of social commentary. The concern is that satirical games may only serve to platform problematic ideologies as some players may relate acritically with the game’s toxic protagonists and themes.

This is further complicated by the unique nature of how satire is presented and interpreted in video games. It appears that satire works differently in video games than other forms of storytelling. Firstly, live-service games like Starship Trooper: Extermination or Helldivers 2 are intended to be played forever. Theylack a traditional narrative arc that offers a didactic resolution to punish the protagonist for their abhorrent behavior. Without the comeuppance of hedonistic, satirical novels and films like Fight Club or American Psycho, games generally lack true moral resolution as players are simply rewarded for their deviant behavior by progressing the game and earning greater abilities, weapons, and in-game cosmetics. Secondly, satire typically requires ridicule by the audience of a character or situation. Given the participatory and immersive nature of video games, the players actually become the intended object of ridicule and may lose the ability to critically view the characters as parodies of themselves. Video games, perhaps more than any other media, see the audience sympathizing with the protagonist whether or not they are the hero. Games don’t always prompt the player to wrestle with the question, “are we the baddies?” (Mitchell and Webb). Successful satire in games must adapt to the idiosyncrasies of the genre. A standout example of this adaptation is The Stanley Parable which cleverly satirizes interactive storytelling as a whole by subverting the conventions of narrator and player choice.

While Starship Troopers: Extermination was largely a commercial and critical flop, it serves to spark the same ideological debates as its original 1959 source material. Themes of militarism, fascism, and moral decline, are just as prevalent across the media landscape now as they were over sixty years ago. However, concerns about declining media literacy and video games’ unique ability to allow the player to inhabit, and sympathize with, the protagonist, call into question the efficacy of satire as a method of social commentary in video games.

WORKS CITED

Squad Troopers, created by xpe and Devlikeapro, 2022, Steam Workshop https://steamcommunity.com/sharedfiles/filedetails/?id=2830905314&searchtext=

Rosenblatt, Kalhan. “A video game has reinvigorated a long-running debate about fascism and satire.” NBC News. 28 Feb. 2024, https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/helldivers-2-fascism-satire-debate-rcna140653

Evans, Greg. “Elon Musk roasted after missing ‘painfully obvious’ message from 1990s sci-fi classic.” The Independent. 16 Nov. 2024, https://www.the-independent.com/arts-entertainment/films/news/elon-musk-trump-starship-troopers-meme-b2649528.html

Mitchell, David, and Robert Webb. That Mitchell and Webb Look, season 1, episode 1, BBC, 2006.

Drew Adan is an archivist with the M. Louis Salmon Library at The University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH). Before coming to UAH, Drew worked for ten years in the Yale University library system at the Lillian Goldman Law Library and Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. He holds an MLIS from Simmons School of Library and Information Science and a Master’s degree in History from UAH. In 2024 he published a book chapter entitled “Space City, USA: The Theme Park of the South that Failed to Launch” in NASA and the American South and has presented on various archival and history topics at national and international conferences.