Features

Thirty Years Later: Sacred Scripture, Ghost in The Shell, and Our Lady of Perpetual Cyberpunk

Despite its initial commercial underperformance and lukewarm critical reception, Mamoru Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell (1995) experienced a cult renaissance in the years following its release due to home video sales. It made a hard connection with a highly influential group of filmmakers such as the Wachowski Sisters, Steven Spielberg, and James Cameron, who publicly described Oshii’s film in The Guardian as “a stunning work of speculative fiction . . . the first to reach a level of literary excellence” (Rose). The interest in Oshii’s film has not waned as a live-action remake of Ghost in the Shell was released in 2017, and a 4K limited rerelease ran in select IMAX theaters in the U.S. in 2021. In addition to its paradoxical use of cyberpunk trappings to tell a story that resists the usually grim outlook of technological proliferation within the genre, Oshii makes use of uniquely Western Christian archetypes for meaning and metaphor rather than spectacle, as is the usual norm in anime. Oshii’s visual symbols are often religious and distinct from the use of Christian symbols in contemporary works such as Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995–96, Shinseiki Evangerion) which serves no authentic story-telling purpose as Brian Ruh argues in Stray Dog of Anime (54-55). However, the usual interpretation of the film, and perhaps even an interpretation through a Christian framework, falls short of describing the fullness of Oshii’s use of the Christian mythos in Ghost in the Shell. To interpret Oshii’s symbolism as solely Christian is too broad a description for there is a denominational distinction becausewithin that overarching Christian framework, exist older and more telling motifs, the severity and specificity of which can only be described as uniquely Catholic. Oshii employs these Christian and specifically Catholic symbols, as this paper will how, to explore the near-universal desire for evolution, transcendence, and, ultimately, some semblance of an answer to the eternal questions.

Neon Genesis Evangelion is a contemporary to Ghost in the Shell due to its release date and overlap in genre. Neon Genesis Evangelion also uses Christian symbolism, biblical allusions, elements of Shintoism, Judaism, and even creature names such as “Adam” as parts of a universe in order to create an entertaining, high-fantasy mythos. Ghost in the Shell goes much further in developing these motifs by embracing a singular Catholic vision as the central theme and metaphor in a speculative cyberpunk universe. This metaphor serves to sustain Oshii’s argument for the redemptive and even divine qualities of technology as a forceful contrast to the fundamental cynicism of the cyberpunk and tech-noire genres.

Certain Catholic rather than simply Christian clues emerge from Oshii’s life that bring clarity to the director’s enigmatic use of religious tools of expression. Richard Suchenski writes in Senses of Cinema that Oshii at one point seriously considered entering a seminary to become a priest. Brian Ruh, meanwhile, maintains that Oshii’s consideration of seminary was only to study religion (8). Oshii himself stated in a 2004 interview: “When I was in college, I was always interested in Christianity and religion… I even thought of transferring to a Christian seminary… It’s really the phenomena created by religion that I’m most interested in, rather than religion itself” (Mays). This fascination permeates Oshii’s body of work. However, a merely Christian reading of a work is too easily perceived as a default Protestant reading to a Western audience whereas one must take into account the flavor of the Christian framework from Oshii, the would-be priest. While the tiny percentage of Japan’s population identifying as Christian is approximately evenly divided between those identifying as Protestant or Catholic, to a Japanese audience, the difference between the two sub-categories is an irrelevancy, argues Ishikawa Akito, Professor of Religion at Momoyama Gakuin University. In the West, however, the distinction between Catholic and Protestant is of grave importance, and the Catholic distinction is critical in Oshii’s Christian framework, especially to an American audience. In the case of Ghost in the Shell, Oshii’s use of Christianity is founded upon a Catholic rather than Protestant reading of the Christian mythos and is employed accordingly in his filmography—a non-distinction for a Japanese audience, as Akito argues, but a serious one for the Western viewer.

The hardboiled skepticism from other 80s and 90s tech-noir media conveys a general caution about humanity’s relationship with technology, but Oshii resists this trend by elevating technology to a divine position through interlacing technology’s place within the Holy Family of Catholic teaching: Jesus, Joseph, and Mary. Oshii employs this trinity of the Holy Family to affirm humanity’s push towards technological advancement and hybridization, as opposed to the “criticism of the extreme enthusiasm of mankind about science and technology” found in Neon Genesis Evangelion and other tech-noir/cyberpunk media (Napier 89). The Catholicism of Ghost in the Shell, therefore, becomes a sustaining metaphor throughout instead of an avant-garde ambiguity; it is not an undeveloped, cross-shaped explosion as spectacle, or a high-fantasy original creature casually named “Adam.” Instead, Oshii uses the Holy Family metaphor to describe the potential divinity of technology in Ghost in the Shell, with Batou as the chaste St. Joseph the Protector, Major Kusanagi as the Virgin Mary, and the Puppetmaster-Kusinagi hybrid as the newborn Messiah. The Messiah’s body serves not only as a representation but is, within the universe of Ghost in the Shell, the nexus of humanity and divinity, the higher order of technology as humanity’s saving grace. Oshii uses the tools of Catholicism in a secular though highly spiritual manner to perpetuate his tradition of “[alluding] to religion to say something deeper about the human condition” (Ruh 55). Ghost in the Shell can be seen as an example of how Japanese content producers use the images and writings of Christianity; for instance, Kusanagi and the Puppetmaster repeat, almost verbatim, in two separate points in the film, the language of Paul the Apostle in 1 Corinthians 13:11-12: “When I was a child, I talked like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child. When I became a man, I put the ways of childhood behind me. For now, we see only a reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face.” But it is also a distinctly Catholic work which makes use of the Holy Family of Catholic doctrine and iconography to offer a secular yethopeful image of the future using metaphors typically reserved for the spiritual realm. Despite all the blood and violence (in the film and in the history of Catholicism), the image Oshii produces is an optimistic theory and suggested map of the next stage of human evolution where technology is not only a boon to ease humanity’s temporal suffering but, from the images of descending angels and mysterious recitations of the Epistles, a divine path forward towards apotheosis.

The trinity of the Holy Family of Catholicism is manifest in the three major characters of Ghost in the Shell. First, Major Kusanagi’s chaste nakedness recalls the Virgin Mary, the mother of Christ. Second, Batou fills the role of St. Joseph the Protector in his platonic relationship with Kusanagi. Third, the Christ child at the end of the film, conceived from this higher power, is preceded by the visiting angel, Gabriel (see Fig. 1). It is not the conventional Christian symbolism employed by typical directors; it is instead the intensely violent and bloody Catholic imagery that unlocks these ancient archetypes and makes Ghost in the Shell a counterclaim for the transcendent potential of technology super-imposed upon a grim tech-noir, cyberpunk context.

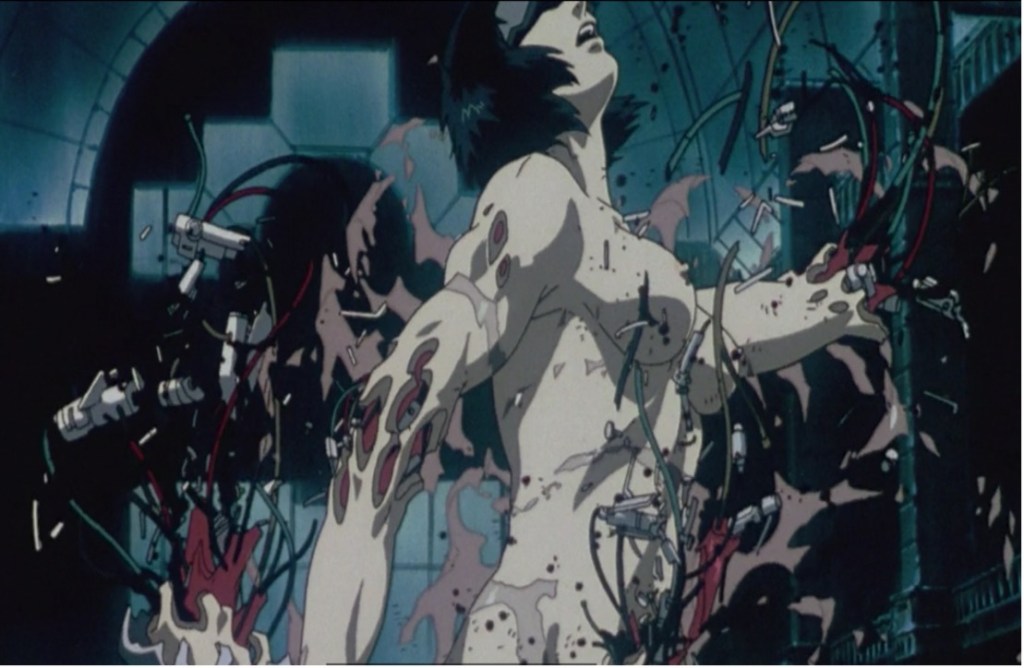

Major Kusanagi’s nakedness functions as fan service on one level, but more importantly, Oshii emphasizes the nudity to convey a statement on sexuality or, in this case, the lack thereof; the Major has no sex organs. The cyborg is drawn seamlessly around the hips. This is not a loophole to bypass Japanese censors. Oshii chooses to make a point of slamming the viewer in the face for the first ten minutes of the movie with a torso with no visible sex organs. However, despite this lack of an opening, and despite the fact that Kusanagi herself states, “I cannot bear children” (1:11:43-44), she is given a full set of breasts. Due to the lack of sex organs, it is reasonable to conclude that the Major is a virgin. One could argue that, if the Major had once been human before receiving her cybernetic body, perhaps she was not a virgin; however, that objection is irrelevant since, in keeping with a Catholic reading, the Major immaculately receives a new body as demonstrated at the beginning of the film (see Fig. 2). A tension also exists within the popular consensus, as reported by fan wikis, that the Major may, in fact, be solely cyborg, her memories of an original body as artificially constructed as the poor ghost-hacked truck driver in the first half of the film. At one point in the film, she even speculates, “Maybe there never was a real me in the first place, and I’m completely synthetic like that thing” (0:42:36-41). The Major’s chaste nakedness in the film contrasts with the almost hyper-sexuality of the Kusanagi of the manga source material, but this departure from source material is a matter of course for Oshii.

The presence of breasts, the means of nursing, in the assassination scene before the beginning credits, contrasted with the lack of exposed sex organs, indicates a being not of carnal sexuality but rather of sexless motherhood like the Virgin Mary; the Major bears the means of nursing but not the gifts of sexual pleasure, sexual union, or procreation in any typical sense. Oshii denies Major Kusanagi even the chance of traditional sexual agency, thus maintaining her virginity. Like Mary, Major’s motherhood is a gift from a higher force; she is meant for union with this higher force of technological divinity because carnal or human sexuality is too base to give birth to the new creature who emerges at the end of the film. Therefore, Kusanagi is equipped with neither the urge nor the ability for sensual pleasure or physical reproduction but a far more substantial motherhood—a divine motherhood explained through the metaphor of high technology.

Major’s consent to the Puppetmaster for a generative union is a parallel to Mary’s Fiat in Luke 1:38: “May it be done to me according to your word.” Susan Napier states that “it is [Kusanagi’s] body, standing at the nexus between the technological and the human, that can best interrogate the issues of the spirit” (107). The vision of technology as not only good but divine in Ghost in the Shell takes up residence in the womb of a cyborg, for in such an affirmation of technology Kusanagi is already connected to this world as Napier’s nexus. This conception manifests the Catholic teaching that the Virgin Mary was without sin before, during, and after the conception of the Messiah through the Marian dogma of the Immaculate Conception. As the nexus, Kusanagi already has a foot in the world of the divine/technological, but this important presence in the world of sinlessness loses meaning for a Protestant Christian framework which is either hostile to or unconcerned with the Marian doctrine of Immaculate Conception and her perpetual virginity: however, it gains momentum when seen from the Catholic perspective. The doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, as promulgated in the 1854 Ineffabilis Deus states that Mary was free from original sin, a teaching rejected by Protestants (Elwell 595-596). Just as Mary was without sin, the Major is “full of grace” and, as Napier’s nexus, simultaneously occupies the divine space of the technological, manifested in the image of the descending angel, as well as the familiar physical space of flesh and blood; Batou says to Kusanagi, “You’ve got human brain cells in that titanium shell of yours” (42:42-45). She is thus uniquely worthy to participate in the birth of the Messiah.

Kusanagi’s own Immaculate Conception at the beginning of the film shows the Major receiving her new body. The Major assumes a fetal position (Fig. 2) within the water-filled womb from which she emerges, taking on the divine technology within and upon her ghost so that she may be ready to accept the gift from on high. Though born into the baseness of flesh, both Major and Mary’s bodies are literally reconstructed in the image of the divine, a technological Imago Dei and, most importantly, without the essential sin that comes with a humanity bound to its flesh. The Major is reborn through the technologically divine intervention of Oshii’s Immaculate Conception—in this case a divinely digital one, and Kusanagi, the nexus, is now ready to carry the seed within her redeemed womb of sacred wires, holy circuits, and metal (Fig. 2).

Batou has a sexual tension with the Major that he does not indulge, even internally. For example, Batou struggles with this tension on screen, as he winces when he sees the Major unzip her dive-suit in the boat (Fig. 3). He turns away in embarrassment while gritting his teeth (Fig. 4), for he is ashamed that he, as St. Joseph, would even consider the Major in a manner outside of her divinely appointed role; even Batou’s eyes are unequipped for carnal desire, being artificial inserts with a range of tactical filters.

Batou is the chaste St. Joseph, the adoptive father of Christ and the protector of the Holy Family in Catholic doctrine. It is Batou, who later arrives with his self-described “standard-issue big gun” (1:06:12-14), who saves the Major from being crushed by a tank. Though this dynamic may appear to be a muted sexism where the damsel must be rescued, it is vital that Batou fulfill this role within the Holy Family as St. Joseph, the Protector. It is Batou who takes the bullet into his own flesh for the Major in the ending scene, giving her more time to do her great work. It is Batou who cares for the new child at the end of the movie, even though the child is not his biological offspring. It is Batou who covers Major Kusanagi’s nakedness when she must shed her clothing during the employment of thermo-optic camouflage (Fig. 5). This chaste feature of Batou parallels St. Joseph’s own story within the Holy Family. St. Joseph’s relationship with Mary and Batou’s relationship with the Major are chaste ones; a feature that separates the Catholic vision of the Holy Family from a Protestant one.

“The Protector” has been St. Joseph’s role in Catholic tradition since the beginning but became official in 1882 when Pope Leo XIII declared him so. In the Bible, when Herod searches out the children to be killed, Joseph takes Mary and the newborn Christ to Egypt (Mathew 2:16–18); when the Major, the Puppet Master, and the new being they create are likewise ordered to be killed, Batou protects them with his own body (1:13:39), and he leads them away to his hiding place. When Batou has hidden away the Major (and the new child of whom she is part) in his own safe house, it parallels St. Joseph the Protector who “…did as the angel of the Lord had commanded him and took his wife into his home” without hesitation or objection (Matthew 1:20). Batou takes his place within the Holy Family, acting with an uneasy obedience to this higher force and in agreement with the Fiat of the Major. It is his role to stand by, keep watch, and protect while the Major and this entity from beyond work to redeem the world.

Even more overt than Oshii’s interjection of scriptures is the robed, glowing angel with feathered wings descending from the light near the end of the film (Fig. 1). The vision of the angel in question functions on three levels, but only one of these is complementary to the Holy Family of Roman Catholic doctrine. The first interpretation of the angel’s descent and the accompanying cascade of feathers fits Oshii’s use of Catholic teaching: this otherworldly creature, as a Christian figure, serves effectively as a secular symbol to represent a being of higher order. Its appearance communicates to the audience and to Kusanagi that she is about to make contact with this higher order, and some kind of transcendence is about to occur. A second interpretation, and the one which explains the presence of the child at the end, is that the angel is Gabriel, the messenger angel (Luke 1:26–35). The angel is descending to announce to the Major that she is to conceive a child with the help of a great and otherworldly force. Then, in the following scene, in a hailstorm of bullets, bodies are destroyed and ripped apart in the throes of the labor pangs (Fig. 7). Despite even Batou’s best efforts to shield her (Fig. 8), Major’s body is eventually pierced by the bullets from the helicopters above, just as Mary’s soul was pierced as foretold by St. Simeon in Luke 2:35: “And a sword will pierce your very soul”The helicopters approach bearing modified snipers; when they come into position, the vehicles unfurl the segmented wings of a dragon with glowing red eyes (Fig. 6), the same dragon from Revelation who follows the pregnant virgin into the desert waiting to devour the child at its moment of birth (Revelation 12:2–4).

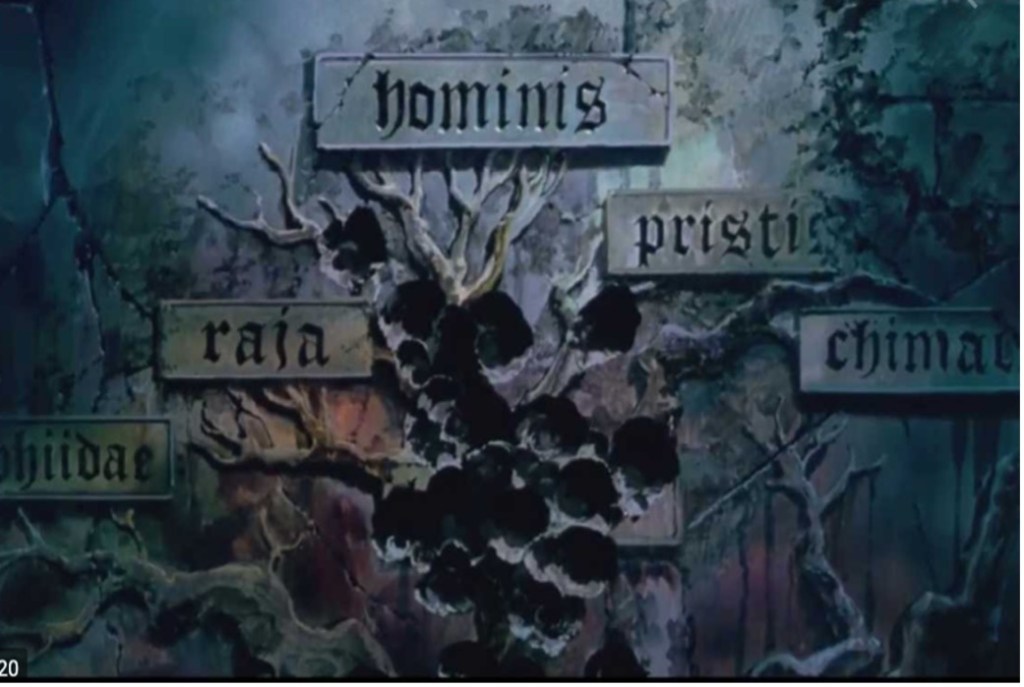

Nearby, the entire hierarchy of evolution leading to “hominis” as the pinnacle form of natural selection is shown on the engraving of the tree (see Fig. 10). It is a tree similar to the one found in Oshii’s Angel’s Egg (1985) with its cross-carrying soldier and retelling of Noah’s Ark, but this tree is riddled with bullet holes from the tank’s auto-cannons, foreshadowing the disturbance of the natural order that must occur, for this next step will not be a linear and incremental natural selection; it is a disruptive leap into the unknown.

Batou takes the Major away, sparing her the indignity of the incoming soldiers out to fulfill their orders from King Herod. In the following scene, we see the child. This child bears the face of the Major, for indeed, it is appropriate that the savior carries one half of its mother’s DNA. This is the savior with a foot firmly planted in both worlds. It is the Emmanuel whose arrival has been foretold by the descending angel in the film. It is totally singular and made substantial only through the Major’s Fiat; therefore, it bears her face and her voice.

Through these Catholic archetypes, Oshii does not anticipate a slow incrementalism, for his view of the next step of human evolution involves violent, painful birth and perhaps even a savior to emerge in the divine light of unhindered technological pursuit. His bloody and Catholic symbolism is fulfilled and sustained far more than the casual Christian imagery of a Protestant nature. However, Oshii’s Catholic framework does not serve as one-to-one allegory for the purpose of religious evangelism. Rather, its purpose is that of technological evangelism; the film makes use of the deeply held preexisting Catholic archetypes to convey the image of the next stage of human evolution. It will happen all at once, and it will be the most destructive force of our creative potential. Oshii affirms this new creation, despite the death and pain of metamorphosis, as the new creature asks aloud to itself, “And where does the newborn go from here? The net is vast and infinite” (1:17:35–42).

Oshii does not draw a traditionally Catholic conclusion in his Platonic journey from the Cave; this “net” is not Heaven. As Napier argues, it is “a reference not only to cyberspace but to a kind of non-material Overmind . . . which does not offer much hope for [the] organic human body” (105). Ultimately, Ghost in the Shell suggests “that a union between technology and the spirit can ultimately succeed” (114), and in Oshii’s universe, technology has taken on divine status. To communicate this prophetic statement, Oshii adopts the Catholic metaphor of the Holy Family. The nexus cyborg Major Kusanagi, who is full of grace due to the wires and microchips embedded in her flesh, gives birth to the new creature that is half of Kusanagi but also half of something else so much more. In Ghost in the Shell, Oshii has appropriated the symbols of Catholic theology to state his hypothesis of a secular transcendence. This transcendence is an alternative answer to the visions of heaven and salvation promised by the Abrahamic faith traditions and an alternative to the dire warnings of the cyberpunk genre where technology becomes the means of humanity’s salvation rather than destruction.

WORKS CITED

Akito, Ishikawa. “A Little Faith: Christianity and the Japanese.” nippon.com, May 30, 2020. https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-topics/g00769/a-little-faith-christianity-and-the-japanese.html

Catholic Church. Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd ed. Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2019.

Elwell, Walter A. Evangelical Dictionary of Theology. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2001.

Faxneld, Per. “Blavatsky the Satanist: Luciferianism in Theosophy, and its Feminist Implications.” Temenos 48, no. 2 (2012): 203–30.

Ishikawa Akito, “A Little Faith: Christianity and the Japanese,” nippon.com, May 30, 2020.

Leo XIII. “Pope Leo XIII: Prayer to Saint Joseph.” udayton.edu. University of Dayton, 2022. https://udayton.edu/imri/mary/p/pope-leo-xiii-prayer-to-saint-joseph.php#:~:text=Blessed%20Joseph%2C%20husband%20of%20Mary,him%20from%20danger%20of%20death

Mays, Mark. Machine Dreams A talk with visionary Japanese animator Mamoru Oshii about his new film Ghost in the Shell 2. Other. Nashvillescene.com. Nashville Scene, September 16, 2004. https://www.nashvillescene.com/arts_culture/machine-dreams/article_b50d24f8-5092-55ff-a567-6c1bc6c243ac.html

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. Burnaby, BC: Simon Fraser University Library, 2018.

Meehan, Paul. Tech-Noir: The Fusion of Science Fiction and Film Noir. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2018.

“Motoko Kusanagi: Ghost in the Shell Wiki.” Fandom. Last modified June 2, 2021. https://ghostintheshell.fandom.com/wiki/Motoko_Kusanagi.

Napier, Susan. Anime from “Akira” to “Princess Mononoke”: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation. New York: Palgrave, 2001.

Oshii, Mamoru. Ghost in the Shell. 1995; Beverly Hills, CA: Anchor Bay Entertainment, 1998. DVD, 82 min.

Rayhert, Konstantin. “The Postmodern Theology of ‘Neon Genesis Evangelion’ as a Criticism.” Doxa no. 2 (30) (2018): 161–70. doi:10.18524/2410-2601.2018.2(30).146569.

Rose, Steve. “Hollywood is haunted by Ghost in the Shell.” The Guardian, October 19, 2009. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2009/oct/19/hollywood-ghost-in-the-shell.

Ruh, Brian. Stray Dog of Anime: The Films of Mamoru Oshii. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Palgrave, 2013.

Suchenski, Richard. “Oshii, Mamoru.” Senses of Cinema, July 2004. https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2004/great-directors/oshii/.

Brian DeLoach, PhD, is an instructor of composition and independent researcher. He has been published in various political publications, outdoor magazines, journals of education, and has been a contributor to the best-selling Teacher Misery series of books. He lives in Cleveland, Tennessee.

Savannah Welch is an artist and student at Polk State College, where she tutors her peers in writing at the Teaching and Learning Center on campus.