⮌ SFRA Review, vol. 50, no. 2-3

Nonfiction Reviews

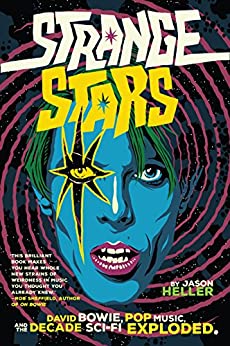

Review of Strange Stars: David Bowie, Pop Music, and the Decade Sci-Fi Exploded by Jason Heller

Nathaniel Williams

Jason Heller. Strange Stars: David Bowie, Pop Music, and the Decade Sci-Fi Exploded. Melville House, 2018. Hardcover. 254 pp. $26.99. ISBN 9781612196978.

Jason Heller’s Strange Stars: David Bowie, Pop Music, and the Decade Sci-Fi Exploded covers the synergy between science fiction and popular music during the 1970s, and it comes at an important point in SF history. More on that last bit later. First, let me cover a few representative factoids the book presents:

- David Jones—before changing his last name to Bowie and penning the song “Starman”—read Robert Heinlein voraciously, including the author’s 1953 juvenile novel coincidentally(?) titled Starman Jones.

- Pre-teen Jimi Hendrix was such an SF-media fan he insisted on being called “Buster,” after Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon serial star, Buster Crabbe.

- The Byrds loved Arthur C. Clarke and composed their song “Space Odyssey” when they learned that would be the title of a film adaptation of Clarke’s “The Sentinel.”

- A 1968 song mocking American astronauts, Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band’s “I’m the Urban Spaceman,” was produced by “Apollo C. Vermouth,” a pseudonym that hid its actual producers–the Beatles’ Paul McCartney and Gus Dudgeon, who went on to produce Bowie’s “Space Oddity.”

These insights are from just the first 14 pages of Strange Stars, and it’s a fair accounting of the rest of the book’s contents. About every third page offers some remarkable, obscure fact about science fiction touching rock history or vice versa. Readers fascinated by such moments will have a blast reading Strange Stars.

But Heller’s book is more than just a cornucopia of hipster trivia. It’s a compelling, comprehensive work that invites us rethink two of the twentieth century’s most influential pop cultural creations. Heller skillfully uses David Bowie’s career as a through line, which prevents the book from simply becoming a list of neat coincidences. Moreover, he focuses exclusively on the 1970s, which may disappoint readers interested in more recent SF/pop artists, but nevertheless provides the book a much-needed focus. The 1970s gave us both Devo’s Island of Dr. Moreau (1896)-inspired album Are We Not Men? and Meco’s Star Wars-inspired disco music; Heller joins these dissimilar stories into an intelligent whole.

The highlights you’d expect are here: Michael Moorcock collaborates with the band Hawkwind; Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land (1961) inspires David Crosby’s ode to threesomes, “Triad”; Paul Kantner and Jefferson Starship get a 1971 Hugo nomination for their concept album Blows Against the Empire; etc. Heller, however, also covers many lesser-known acts, such as the synth band Lem (named for Solaris author Stanislaw) and French group Heldon, who composed an entire album inspired by Frank Herbert’s Dune (1965). Heller also recognizes heroines like Nona Hendryx, who used her interest in SF to influence the song content and fashion design of funk band Labelle.

Bowie—who inspired many SF-related bands, praised them in the press, and hired their members as backing musicians—ties to the book’s chronological structure and its thesis. He enters the 1970s known primarily for “Space Oddity,” the quintessential SF subject-matter song. He quickly assumes his Ziggy Stardust persona, embodying the science-fiction character on his eponymous album. He ends the 1970s having left behind Ziggy’s overtly sf narrative lyrics (“I’m a space invader”!) in favor of synthesizer-driven, atmospheric albums like Low (1977), a whole different kind of otherworldliness. Heller states, “Like his new friends in Kraftwerk, [Bowie] had come to eschew singing about science fiction. Instead he was science fiction” (148). This figures into Heller’s argument that there are really several strains of science fiction music. One is primarily narrative (think Rush’s 1976 album 2112). Another appropriates SF’s imagery (think guitar/starships on Boston’s album covers). Artists who encompass all those strains—like Bowie, Gary Numan, and P-Funk’s George Clinton, who built from Sun Ra’s Afrofuturist template—deservedly get the most coverage from Heller.

It’s not perfect. Direct artistic influences can be notoriously hard to prove. Heller relies on “likely inspired,” “plausibly,” and similar phrases a little too often, although he’s admirably honest when a perceived influence isn’t 100% verifiable. His consistent use of “sci-fi” rather than SF may frustrate grumpier scholars. My only other quibble is the book’s index; a work that drops this many names needs a more complete one.

Strange Stars offers a canon of SF music and also beckons readers to seek out older SF that influenced musicians. Heller includes a discography of major SF-related songs at the book’s end that will satisfy audiophiles. Just as interesting, however, are moments when specific works pop up more than once. Heller reveals that Moorcook’s novel The Fireclown (1965) inspired musical tributes by both Pink Floyd and Blue Öyster Cult. Maybe it’s time to (re)read The Fireclown? Similarly, Heller recounts how Philp José Farmer’s 1957 novel Night of Light brought the term “purplish haze” to Jimi Hendrix’s attention, and how Kantner used Eric Frank Russell’s The Wasp (1957) for inspiration. There’s a whole, neglected sub-canon of 50s and 60s SF that inspired musicians. Instructors who regularly teach New Wave-era SF could conceivably look to Strange Stars for new syllabus material.

Finally, the SF community needed a book like Strange Stars. In 2013, we lost Paul Williams, the Philip K. Dick scholar and founder/editor of Crawdaddy!, one of rock journalism’s earliest major periodicals. David Hartwell (to whom the book is dedicated) began his career writing for Crawdaddy! and became one of SF’s leading editors before his death in 2016. The individuals who were at Ground Zero for the SF/rock ‘n’ roll explosion—who loved both phenomena and understood their interconnectedness at a cellular level—are leaving us. Spurred on by those deaths, as well as Bowie’s in 2016, Heller understands that these stories needed to be documented while their sources still live. Some of the book’s more rushed moments seem attributable to this sense of urgency. Strange Stars probably isn’t for every science fiction scholar or fan, but for anyone who cares about SF’s conversation with twentieth-century pop culture, it’s indispensable.