⮌ SFRA Review, vol. 56 no. 1

Features

Jules Verne’s Vision of Green Cities for Today

Quentin R. Skrabec

In 2022, the French Embassy to China unveiled its annual Franco-Chinese Month of Environment, focusing on Jules Verne and “his advocacy, curiosity, passion, and care towards the environment, especially oceans. “Throughout November 2022, a series of educational and cultural events featuring Verne lectures and scientific activities was scheduled in approximately 20 Chinese cities to draw the public’s attention to the current environmental challenges through Jules Verne’s literature” (European Union News Letter, 2022).

Verne wove the environment into the very heart of the plot and themes of many of his novels. His stories often show the pollution, health concerns, and bleakness of industrial cities. Verne frequently lamented the plight of industrial workers and capitalistic slave labor, as in Verne’s The Mighty Orinoco in 1898, while being in awe of industrial progress. Verne’s books lacked the social directness and poignancy of Charles Dickens, but they still highlighted the problems that can come with industrialization. Unlike Dickens, Verne offered solutions as part of a lifelong quest for green energy and healthy living conditions.

In 1863, Jules Verne’s “first” novel, Paris in the Twentieth Century, envisioned a futuristic green city, albeit a dysfunctional urban center, that started a 60-year green literary and scientific journey that addresses numerous environmental issues and offers many lessons for us today. Verne’s novels often contrasted environmental extremes, and his characters were conflicted over the balance between scientific progress and environmental concerns. Verne excelled at framing the struggle. He hated the air and water pollution that scientific progress often brought, and many of his novels address green energy alternatives. Verne believed electricity and the hydrogen derived from it could replace coal as technology evolved. He proposed alternative green energies to generate electricity, such as wind energy, hydroelectric, super chemical batteries, rechargeable batteries, compressed air, solar power, tidal wave dams, electromagnetic “accumulators,” thermal energy from the oceans, and harvesting static electricity from the air. For the transition from coal, Verne explored new, efficient, and cleaner energy uses, such as clean coal technology, more efficient engines to replace steam engines, and efficient lighting systems. This article details and analyzes his extraordinary journeys in green urban engineering, highlighting the realization of some of his key insights.

The suggested iconic relationship between Verne and the coal-fired steam engine is far from true. He struggled with the relationship between technology and the environment, wishing they could coexist. In Verne’s futuristic Paris, Verne tried to warn and address urban pollution issues, technology versus the arts, and the limits of technology versus nature.

Like many of his readers, Verne found the root of both environmentalism and industrialism. Verne has inspired both naturalists and engineers. It was this common ground of the natural sciences that Verne found hope in creating unity with environmentalism and technology. Many engineers, even today, find their first love of science in grade school nature study. Verne believed that maybe there was a middle destination and that even industrialists could be environmentalists, although he feared that it might never be achieved. In Verne’s vision of the struggle, both sides might find a compromise. However, with age, he grew more pessimistic.

Verne’s “Carbonivorous” World

Verne had an ambiguous relationship with coal. Verne saw the dependency of Victorian society on coal as both an economic and environmental problem. While he envisioned lean energy inventions, such as hydrogen cars, steam engine replacements, clean coal-burning systems, compressed air-driven trains, wind power, hydroelectric power, and electric lights, he still saw a future of some limited coal-burning pollution in his futuristic vision of 1960 Paris (Verne, Paris in 20th Century, p. 157). He fully realized that replacing coal would be challenging even in the future. In Purchase of the North Pole (1889), Verne says, “The stomach of industry thrives on coal: it will not eat anything else. The industry is a carboniferous animal” (Verne, Purchase of the North Pole, p. 49). In his futuristic Paris, which he looked ahead 100 years, he still saw a smaller but stubborn dependency.

The age of Verne was dominated by coal. Victorians at first saw coal as a boundless energy source, albeit a dirty one. Verne framed an entire novel, The Underground City, in 1877 to discuss the coal mining industry. He highlighted the use of coal in steel and ironmaking in his novels Begum’s Millions (1879) and Mysterious Island (1875).

In his 1875 novel Mysterious Island, Verne correctly predicted the exponential nature of coal consumption. “With the increasing consumption of coal. . . it can be foreseen that the hundred thousand workmen will soon become two hundred thousand, and that the rate of extraction will be doubled” (Verne, Mysterious Island, p. 188). Verne saw this exponential doubling as being driven by the then-emerging use of coal in steelmaking, which, by the late 1880s, had become the primary sector of coal consumption. In the 1880s, coal usage in the steel industry was more prominent than its use as a heating fuel. Verne anticipated a massive future increase in the use of coal in steel and iron in Begum’s Millions (1879), which would occur in the twentieth century.

Like his fellow Victorians, Verne initially saw unlimited sources for their appetite for coal. In 1859, a traveling young Verne saw Scotland’s great coal mines, submarine coal veins, and the “sea coal” on the beaches, noting there was coal “enough to supply the world” (Verne, Backwards to Britain, 1859). Even if the exponential consumption continued, Verne believed there would be time for technology to find more coal deposits or replace coal, and he often noted this in his writings. Verne initially saw excess consumption as a problem for future centuries.

In his 1863 Journey to the Center of the Earth, a Verne character proclaimed, “Thus were formed those immense coalfields, which nevertheless are not inexhaustible, and which three centuries at the present accelerated rate of consumption will exhaust unless the industrial world will devise a remedy” (Verne, Journey to the Center of the Earth, p. 57). Like many Victorians, Verne believed that future coal reserves under the sea, as he noted in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1871), would significantly increase the coal supply. Verne believed that the discovery of new reserves and technological advancements would also grow exponentially to meet rising demand. Still, not everybody was optimistic about coal reserves.

Many Victorian scientists, upon witnessing the exponential growth in coal use in the late 1870s, became pessimistic and published articles about potential shortages. The British were extremely sensitive to fuel shortages since the early 1800s, which had led to an urban shift from wood to coal for heating. By the 1880s, much like the 1980s with oil, Victorians started to fear a future of coal shortages (Minchinton, 1990, pp. 212-226), and Verne’s writings began to reflect this. As with oil today, Verne saw an unhealthy need for more coal reserves in the 1800s, leading to global economic pressures, more exploration, and environmental pressures.

Verne, in 1889, novelized a fictional coal exploration project to tap into the vast coal reserves under the Arctic to meet this future demand in [Topsy Turvy,] Purchase of the North Pole (1889). In this novel, Verne foresaw competing international claims on Arctic mineral rights and the attempt to change nature for economic reasons. In Purchase of the North Pole, Verne foresees the possibility of capitalists needing to change the earth’s rotation axis to create a warming of the Arctic to mine its coal. Verne’s plan in that novel was to tap Arctic coal deposits, which he assumed were plentiful. While his methodology here was not his best science, Verne’s prediction of vast coal reserves in the Arctic turned out to be true. A 300-mile-long belt in Alaska has an estimated four trillion tons of coal, one-third of the United States reserves, and an eighth of the world’s coal resources. Verne had a simple plan, yet a grand scale to tap into such reserves. He used giant cannons of his Baltimore Gun Club from his earlier novel, From the Earth to the Moon, to try to shift the Earth’s axis. Noting, “The jolt of its recoil will remove the tilt of Earth’s axis. This shift will give the Arctic region a temperate climate, thus warming the globe” (Verne, Purchase of the North Pole, p. 57-58). His capitalists would then access the large coal deposits believed to be ready for the taking in the Arctic. In Verne’s novel, nature inhibits man from succeeding.

However, Verne’s primary concern with coal was not shortages but air pollution, water pollution, and social problems created by its use. Verne had a love/hate relationship with coal-fired Victorian-era icons such as coal heating, steam locomotives, and steam engines. Verne had noted these concerns early in his career. In his first writings, Verne highlighted the smoke and air pollution of the Industrial Revolution in his 1859 tour of Britain. In his The Will of an Eccentric (1899), Verne defines an even worse environment in industrialized America. His fictional cities, such as futuristic Paris in Paris in the 20th Century (1863), France-Ville in Begum’s Fortune (1879), Standard City in The Self-Propelled Island (1895), and Blackland in The Barsac Mission (1919), were designed to reduce or eliminate smoke and industrial dirt.

In his personal life, Verne sometimes had to balance his fascination with industrial progress and the beauty of nature. Verne loved the fresh air and the cleanliness of the countryside, as well as cruising on his yacht. In the 1880s, Verne ran and was elected to the Amiens city council. He was very active in this role, promoting laws to stop “locomotive smoke from polluting the town” and limiting “trolleybuses’ overhead wires in the public square” (Butcher, p.208). His final home in Amiens was, in many ways, a reflection of the clash between industry, culture, and nature that characterized the Industrial Revolution.

The Dark Side of the Vernian Industrial Revolution

While Verne believed in a possible green future, like Charles Dickens, he addressed the realities of the times. The industrial cities of Verne’s time were dark, smoky, and polluted. Verne’s polluted fictional steel city, Stahlstadt, in Begum’s Million (1879), represented Victorian industrial cities. It had all the literary darkness of a Dickens novel.

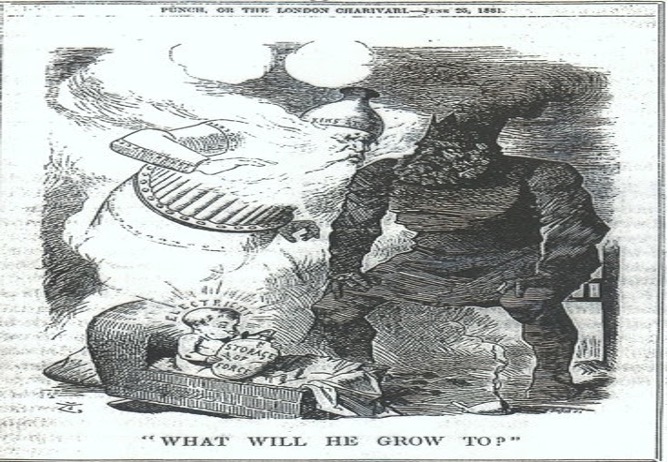

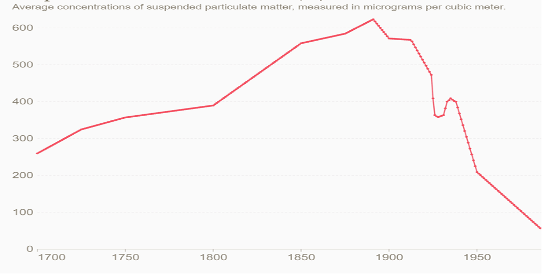

The years from 1820 to 1900 saw a rapid increase in British coal consumption. It rose from 20 million tons in 1820 to 160 million tons in 1900 (an eight-fold increase) (Fouquet, 2011, pp. 2380-2386). Severe timber shortages in the early 1800s drove a crisis-driven shift from wood to coal in home heating, cooking, iron production, and steam production. A half ton of coal produced four times as much energy as the same amount of wood and was cheaper to produce as timber became rare. Despite coal’s bulk, it was easier to distribute. The switch to coal averted an energy crisis but ushered in a pollution crisis. Figure 1 shows the dramatic rise in pollution in the 1800s.

Source: Fouquet, R. (2011). Ecological Economics 70(12), 2380–2389

Verne saw considerable air and water pollution when coal overtook wood for home heating, as in cities like Edinburgh in the 1850s, which he toured and wrote about in his Backwards to Britain (1859). Charles Dickens could have written chapters 15 and 20 of Backwards to Britain. Historians noted, “By the 1800s, more than a million London residents were burning soft coal, and winter ‘fogs’ became more than a nuisance” (Urbinato, 1994, summer) Verne describes industrial 1859 Liverpool as “gas lamps had to be lite by four in the afternoon” because of smoke, “smoke blackened yellow brick and grimy windows” (Verne, Backwards to Britain, p. 59). The streets were filled with coal dust, swarmed with children in rags that “flaunted the misery of England.” His description of Edinburgh was similar. He even described the air of a small French industrial city, Indret, in 1858 as “an atmosphere thick with the tarry emanations of coal” (Verne, Backwards to Britain, p.17). At Edinburgh, he noted the social aspects of pollution: “foul disease-ridden atmosphere” with children begging in rags. Verne would die at the peak of coal air pollution (1905) as new fuels and air quality standards started appearing. Verne hoped science would deliver a cleaner future, but even his futuristic vision of 1960 Paris still had some air pollution from coal usage and chemical plants.

Verne described London’s Thames River in 1859 as a “putrid overflow of sewage.” Coal, however, was the primary source of poisonous water pollution. In the 1850s and 1860s, Europe’s primary municipal industry was coal gas production for lighting and heating. Gas works were built on major rivers, reducing air pollution from coal burning at home, but the big problem with gasworks was that by-products such as tar and benzene chemicals were dumped into the rivers, eliminating fish. The other by-product of dense sulfur dioxide gas was less visible but killed vegetation around the gas works. This sulfur dioxide also attacked the beautiful stone architecture and statues, which Verne noted in his 1859 tour of Britain.

The main characteristic of the atmosphere of London in 1873 was a coal-smoke-saturated fog, thicker and more persistent than natural fog, that would hover over the city for days. Historians noted, “As we now know from subsequent epidemiological findings, the [1873] fog caused 268 deaths from bronchitis. Another fog 1879 lasted four long months with little sunshine from November to March” (Fouquet, 1990, p. 2384). London was typical of European cities. In building his fictional underground town in 1877 (Underground City/Child of the Cavern) to rival Edinburgh, Verne describes Edinburgh as having “an atmosphere poisoned by the smoke of factories” (Verne, Underground City, p. 122). Air pollution in Paris by the late 1870s was deemed equivalent to Edinburgh and London.

Verne’s industrial world only worsened in the following decades as iron production increased. Coal for iron and steel production had created most of the smoke and dust pollution in the late 1800s. In 1899, a Verne fictional train traveler in The Will of an Eccentric described the Iron City of Pittsburgh’s atmosphere as capable of making ink by placing a glass of water out overnight. Verne went further, describing the pollution and destruction of nature seen on a rail trip from Chicago to Pittsburgh, ironically, as “that is progress.” Steel production increased nearly 40-fold in Europe between 1870 and 1912 (and more than 90-fold in Germany for the same period), causing an explosion in coal-driven air pollution.

The rapid technological progress and its pollution had left Verne conflicted. He loved science and technology, but he saw the problems that Charles Dickens had seen. Verne’s novels often deal with stark contrasts, such as in Begum’s Millions (1879). In many stories, he highlights the inherent conflicts of Victorian times, such as industry versus the environment, distribution of wealth, misuse of technology for war, science versus the arts, totalitarianism versus democracy, technical versus liberal arts education, practical versus idealism, industry versus agriculture, and capitalism versus socialism. Verne chronicles his futuristic visions with solutions, hopes, warnings, inconvenient truths, and concerns. He was both an industrialist and an environmentalist, much like Henry Ford (Skrabec, 2010). He saw room for compromise but was pessimistic that it could be achieved. His characters, like his stories, are conflicted and full of contrasts.

Verne was not alone in his belief in a compromise between industry and the environment. William Armstrong, one of Britain’s great engineers and often noted by Verne, was an early advocate for renewable energy and even hypothesized about future solar power generation. Armstrong believed coal “was used wastefully and extravagantly in all its applications” (Cockburn, 2010). Verne would use many of Armstrong’s ideas in Paris in the 20th Century (1863). This novel became a type of game plan for the future of energy in Verne’s visions.

Verne’s energy predictions and insights in Paris in the 20th Century (1863) laid the foundation for the literary future of energy in Verne’s world and beyond. This 50-year literary history (1863 to 1919) of energy by Verne was at times indeed a series of green adventures extraordinaire. His literary series adventures (Voyages Extraordinaire) would cover and improve upon an array of futuristic energy predictions such as compressed air rapid transit, hydrogen-fueled vehicle engines, new efficient electrical and electromagnetic applications, more powerful sodium batteries, wind power, hydroelectric power, solar power, tidal power, static electricity air accumulators, x-rays, wireless communications, laser beams, petroleum fuels, and new electro-mechanical machines, and new types of efficient engines to replace the steam engine—even some unfilled dreams such as electrical generation from ocean thermal gradients.

Verne’s Green Futurist Paris of 1960

Born in the smoke, dust, and dirt of an Industrial Revolution driven by coal, Verne envisioned a new and cleaner world. Verne began his writing career with a green vision of a futuristic Paris of 1960, a hundred years into the future. It was this fictional green city on the hill whose vision was a muse for Verne’s writing career. Verne’s editor turned down this first novel, Paris in the 20th Century, in 1863. His editor saw it as “simply unbelievable” (Tavis, 1997). The manuscript would be found and published in 1996. It was not only entirely believable, but most of the engineering had been implemented or is being researched today. It also represented the blueprint for his next 50 years of literary journeys into future science.

Verne’s Paris in the 20th Century (1863)would have significantly restricted the use of coal, with green sources supplying the power grid, hydrogen home heating, electric home and street lighting, windmill compressed air factory power, and rail transportation. It would be fueled by high-tech battery electricity, dynamo-generated electricity, hydrogen and oxygen from electrolysis, windmills, compressed air, tidal wave energy, and even air electrical “accumulators.” But even in this futuristic green Paris, coal for chemicals, fertilizers, and public demands for coal gas lighting by shop owners continued to cause some pollution. He realized getting off coal would be long and difficult. Figure 2 is an artistic view of Verne’s Paris.

Verne’s futuristic green Paris was a complex mix of wind, water, compressed air, electrical power, hydro-power, hydrogen for heating, and hydrogen-fueled cars, trucks, and ships. Verne even frames his green city’s needed evolution and a retro historical timeline. He started with windmill-sourced compressed air, powering his initial construction projects, factory machines, and construction cranes. The construction projects included skyscrapers, asphalt roads, sea channels, and canal construction to open Paris and its transportation networks to the sea. Windmills compressed air and drove mechanical devices in factories, homes, and powered trains and railways (Taves, 1997).

The next phase was the electrical power grid. It would be an electrical city with lights, elevators, and other electrical devices such as fax machines and wireless communication. However, Verne does not fully define how massive amounts of electricity would be produced in detail. He notes that an electro-mechanical dynamo (gravity-fed) generated electricity and batteries for small devices. This futuristic Paris did have the potential infrastructure to generate electricity through electromechanical, wind, water, compressed-air, and chemical means. The literary years of Verne to follow were made up of electrical adventures to achieve the massive electrical power needed for his futuristic Paris.

Electrical power would be the basis for another ancillary power source of hydrogen. He foresaw the massive hydrogen production by electrolysis to power cars, ships, and home heating. And maybe to use hydrogen instead of coal to power steam engines. Verne predicted a technical fantasy of hydrogen fuel for cars and home heating, hydropower generation, new efficient carbonic acid (carbon dioxide) engines instead of steam, and replacing coal gas with electric lighting (Verne, Paris in the 20th Century, pp. 24-25).

Verne envisioned a fanciful array of green, efficient, and power-saving inventions, such as carbon dioxide engines, electrical lighting systems, magnetic friction reduction for trains, hydraulic lifting systems, compressed air storage, hydraulic cranes, water turbines, and hydrogen/oxygen/compressed air heating systems, which would augment his green energy sources, improve efficiency, and reduce demand. Verne’s Green New World would also address environment, health, and wildlife conservation in his city design as part of his holistic approach.

The heart of Verne’s green Paris was built on four pillars of green energy: Compressed air and Wind Power, Hydrogen fuel, and chemical electrical power. And a number of energy-saving inventions.

The Power of Wind and Compressed Air of 1960 Paris

You can estimate that Verne’s futuristic Paris was 60 percent electricity-based. The balance of power came from compressed air from windmills and some water power. Jules Verne and his son Michel believed that stored windmill-generated compressed air would be part of a green future. In Paris in the 20th Century, Verne proposed the use of stored compressed air to power railways, factory machines, construction cranes, pneumatic tube trains, moving bridges, and even regulate clocks in a future Paris of 1960. Verne drew inspiration from a 1861 pneumatic compressed air single-car train experiment in London and the use of compressed air technology for the Fréjus Rail Tunnel through Mt. Cenis in the European Alps in 1857.

Verne addressed the inconsistency of wind power by proposing an urban compressed air storage utility. In Verne’s futuristic Paris, compressed air would supply energy through a public utility called the Catacomb Company of Paris. Verne’s windmill compressed air was pumped into and stored in Paris’ catacombs by “1,853 windmills established on the plains of Montrogue” outside the city (Verne, Paris in the 20th Century, p.31). Stored compressed air solves an inconsistent supply of wind energy and solar, making it attractive today. Verne and his son proposed a bright future for compressed air applications in many of his future novels. In the novel Self-Propelled Island (1894), Verne had a compressed air city utility company on his floating island. Similarly, in his book The Barsac Mission (1919), Verne’s city in the Sahara Desert had a compressed air utility.

In Paris in the 20th Century, Verne envisioned high-speed compressed air tube trains for interurban transportation. In his 1888 novel, The Year 2889, Michel Verne, son of Jules Verne, suggested pneumatic trains traveling at 1000 mph (Verne, In the Year 2889, p. 51). This prediction of high-speed pneumatic trains is on the verge of becoming a reality.

In July 2017, Elon Musk’s startup, Hyperloop, successfully tested a full-scale system on its test track in Nevada and reached a top speed of 70 mph. Musk hopes to achieve 250 mph soon. The Hyperloop uses compressed air and magnetic force to reduce friction, as Verne did in his futuristic Paris. Magnetic cushioning was yet another necessary design application of Jules Verne (Verne, Paris in the 20th Century, p.23).

Michel Verne took the vision further with a transatlantic pneumatic tube train from Boston to Liverpool in two hours and 15 minutes. This story was published in English in Strand Magazine in 1895 and was incorrectly attributed to Jules Verne (Verne, Worlds Known and Unknown, p. 262). This pneumatic train could travel at 1000 to 1112 mph, much faster than Musk’s prototype.1

Recently, Popular Science suggested that a transatlantic tunnel is more feasible than previously thought and possible with today’s engineering. Researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences proposed a submarine rail project that would run at a theoretical speed of 1,240 mphclose to Verne’s prediction (Garfield, 2018). A pneumatic transatlantic system is compared favorably with transatlantic pipelines, cargo ships, planes, and cables; the proposed transatlantic system would still cost over 200 billion dollars. Of course, reducing carbon dioxide would help offset the project costs. Verne envisioned compressed air doing much more than trains.

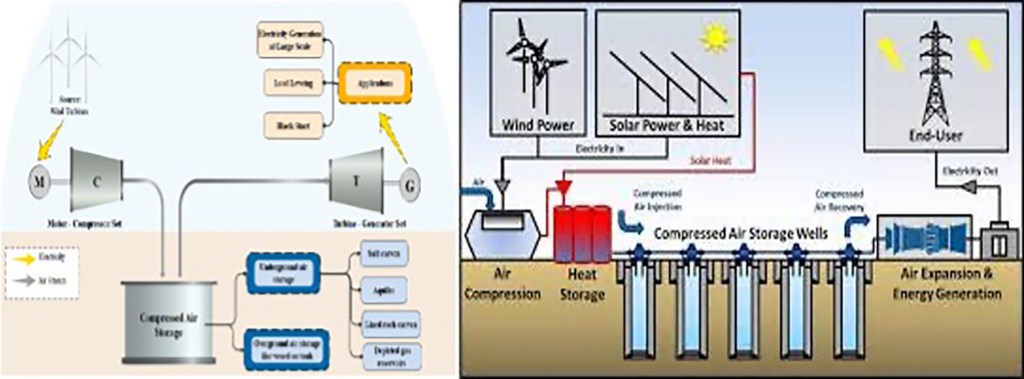

Today’s green energy movement has resurrected Verne’s vision of green compressed air. Compressed Air Energy Storage (CAES) is a potential renewable power grid because it can store power from clean energy sources such as wind turbines and solar panels. Like Verne’s futuristic Paris catacombs, CAES uses underground storage. At the urban utility scale, energy generated during periods of low demand can be released during peak demands. Many competitive thermodynamic designs are being researched, and pilot plants are being built. Of course, any power source can be used to compress air.

Jules and/or Michel in Barsac Mission (1919) used hydroelectric power to run electric compressors to compress air into a liquid. In the Barsac Mission, compressed liquid air was stored in tanks and powered an engine to propel his heliplanes. This air engine was a piston engine using the liquid-to-gas phase transition. In January 2024, the US government’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) awarded research contracts to use compressed liquid air in planes.

Several options are being considered today for manufacturing and applying compressed air. Figure 3 is schematic of the options.

In addition, Verne’s compressed liquid air engine in Barsac Mission is also getting new interest in car engines. All major car companies are doing serious research driven by the zero-emission green movement on compressed air engines. Compressed air cars are not yet very efficient in terms of net energy balance, although Ford and Jeep are improving their engines with an eye on the future.

Source: Kham, Imram. Renewable Energy and Sustainability, Elsevier, 2020

In addition, Verne’s compressed liquid air engine in Barsac Mission is also getting new interest in car engines. All major car companies are doing serious research driven by the zero-emission green movement on compressed air engines. Compressed air cars are not yet very efficient in terms of net energy balance, although Ford and Jeep are improving their engines with an eye on the future.

Electrically Generated Hydrogen For Cars, Trucks, and Home Heating

While Verne’s 1960 Paris had compressed air-driven commuter trains, he also envisioned green hydrogen individual transportation. Verne, in 1863, had no doubt that the future was hydrogen. Verne’s answer to carbon pollution was hydrogen, which would come from electricity. In Verne’s green Paris, hydrogen-fueled trucks, cars, and heated homes. Of course, hydrogen comes from the electrical breakdown of water (electrolysis) into hydrogen and oxygen. As we have discussed, coal in Verne’s time was used for home heating and was the primary source of air pollution. Verne used the method of water electrolysis, used for hydrogen gas heating, for altitude control in his Five Weeks in a Balloon (1863). Verne’s green Paris utilized a similar electrolysis-generated hydrogen for home heating via an engineering system that remixed hydrogen and oxygen fuel to heat compressed air and pipe it to apartments. The design was like his small-scale electrical electrolysis of water to hydrogen/oxygen, which was then remixed to heat the gas in the balloon to lift his balloon in Five Weeks in A Balloon.2 Generating a small amount of hydrogen from battery electrolysis, he was required to design a separate burner pipe to transfer heat safely to the explosive hydrogen gas in the balloon for flight control. It was an ingenious design but still risky, and after the famous explosions of the early twentieth century, non-flammable (but costly) helium replaced hydrogen in the 1920s in balloons and dirigibles.

Verne would later use electrolysis again, found recent fueling interest in hydrogen balloons. In Five Weeks in a Balloon, Verne produced hydrogen by transporting iron and sulfuric acid to the balloon launch site, but in future novels, Verne’s preferred method was water electrolysis. The Weather Service now uses local on-site electrolysis to fill hydrogen weather balloons. The 2023 switch from helium-filled balloons to launching hydrogen-filled balloons significantly reduced costs and carbon emissions (Rappe, 2023).

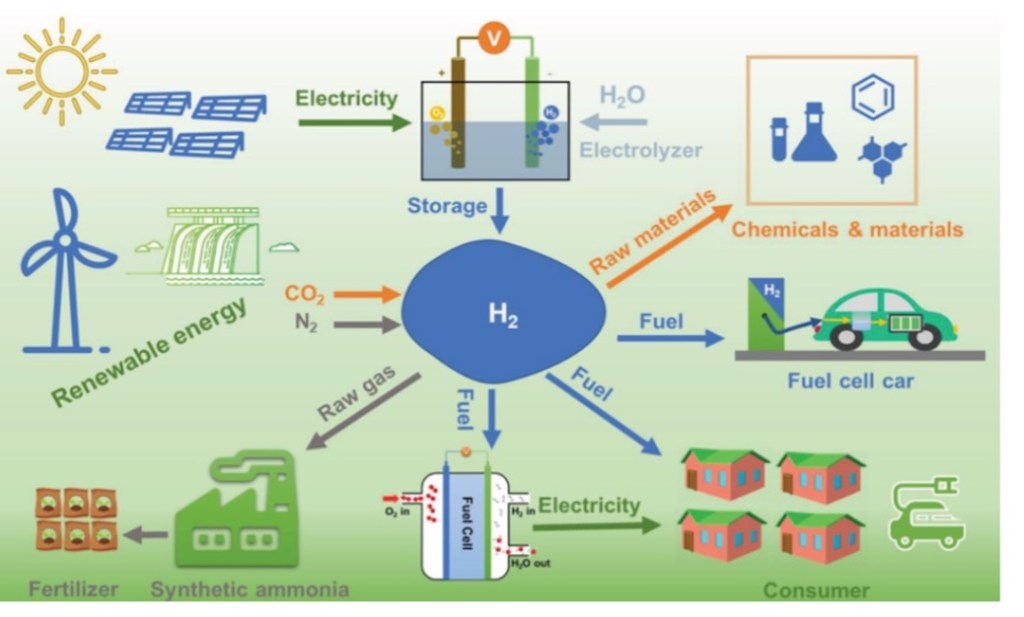

However, it was not hydrogen balloons that inspired Verne but hydrogen as a replacement for coal. Verne saw a much more significant role for hydrogen as a fuel in the future. In Jules Verne’s science fiction novel The Mysterious Island (1875), Verne imagines a world where “water will one day be employed as fuel, that the hydrogen and oxygen which constitute it…will furnish an inexhaustible source of heat and light, of an intensity of which coal is not capable” (Verne, Mysterious Island, p. 189). Verne’s vision of a hydrogen economy was not so much about smaller localized production but the mass production of hydrogen. In his sixty years, Verne evolved the mass production of hydrogen in his scientific and literary quest (Voyages Extraordinaire) from chemical production from iron and acid to battery-powered electrolysis to electromechanical electrolysis.

Verne predicted urban utilities for hydrogen production in Dr. Ox’s Experiment (1872)and Paris in the 20th Century (1863).In Paris in the 20th Century, Verne was unclear on how the electrical power needed for the massive hydrogen would be produced. Still, his futuristic Paris had many possibilities, from battery-powered electricity, electromechanical dynamos, wind, and hydroelectric power, as noted in the novel. In Dr. Ox’s Experiment, Verne used an extensive series of batteries. Like engineers today, Verne realized that batteries could not be a significant source of green hydrogen. It would take the electromechanical dynamo, which Michael Faraday had predicted and Verne was fascinated by. In the late 1850s, commercial dynamos were still evolving, but Verne quickly applied their future use. His last fictional city in The Self-Propelled Island (1897) was a total electric city using petroleum, steam, and electromechanical dynamos to generate electricity.

Some engineers of Verne’s time had envisioned a possible future for a hydrogen economy via commercial production via electrolysis with dynamos. Interestingly, Alliance Company, a hydrogen manufacturing company, made the first commercial electrical dynamos in 1859, originally to produce hydrogen fuel by electrolysis and sell it. Within a few years, the hydrogen proved too costly, difficult to transport safely, and impractical for an extensive fuel network. However, this failure did not alter Verne’s vision in 1863 of its future use. He followed the evolution of the electromechanical dynamo and applied its advance in his future novels. In his Underground City (1877), Verne used coal-powered dynamos, which again were not green. In The Barsac Mission (1919), he used hydroelectric dynamo generation, which was green but limited. By the twentieth century, electromechanical dynamos supplied the world’s electricity. Continued advances in technology have made a hydrogen economy possible.

Verne did augur the emerging green cities where hydrogen could supply heating and transportation. Verne’s use of electrolysis to mass-produce hydrogen is back on the table. These visions are being realized today by Toyota, which is building hydrogen plants using electrolysis that could meet the demands of Verne’s futuristic Paris (Collins,2024). Toyota’s hydrogen plants will power a city that is currently under construction, known as Woven City (Collins, 2024). Toyota’s Woven City will use green hydrogen based on these new engineering efficiencies of hydrogen generation via electrolysis. Toyota will use solar and wind-produced electricity to manufacture hydrogen. Like Verne’s Paris, Toyota’s city will use hydrogen to power trucks and cars, and like Verne, Toyota will use a city-wide network of hydrogen fueling stations. Woven City will supply hydrogen to passenger and commercial vehicles in the city via a pipeline.

Today’s engineering has overcome significant issues such as the cost/energy balance and the inefficiency of electrolysis in hydrogen production. Hysata, a New South Wales-based company that makes electrolyzers, has announced its latest breakthrough: Hysata can generate hydrogen with a whopping 95 percent efficiency. A hydrogen fuel cell electrolyzer/generator at the individual fueling stations will back up power during outages. Figure 4 shows the possible infrastructure of a future economy.

Source: Kham, Imram. Renewable Energy and Sustainability, Elsevier, 2020

Verne’s 1863 vision included hydrogen-powered engines. Verne used clean, burning internal combustion hydrogen cars, which he calls the “Lenoir Machine in his futuristic Paris” (Verne, Paris in the 20th Century, pp. 24-26). In 1858, Etienne Lenoir of France invented the 1-cylinder, 2-stroke engine that used gaseous fuel. The Lenoir Hippomobile in 1860 was fueled by electrolyzing water and running the hydrogen. Later, Lenoir adapted the engine for various gases, such as coal gas. The advantage of burning hydrogen is it exhausts water and no pollutants. Hydrogen cars are still being researched as a green solution for internal combustion. Verne realized the city needed a network of hydrogen gas stations, but he did not address today’s concern about handling highly explosive hydrogen.

Today, green hydrogen is achieved through electrolysis powered by renewable energies such as wind or solar energy coupled with improved process efficiencies even on a smaller scale, such as in fuel stations. Hysata makes electrolyzer units in many sizes and has built pilot plants to supply heavy-duty trucks in California. Amazingly, Verne used hydrogen in Paris in the 20th Century to power trucks.

Verne’s Electrical 1960 Paris—The City of Lights—But How to Power It?

Verne’s future Paris was an electricity-based city, and besides generating hydrogen, Verne’s green futurist Paris was electrical in many areas, much like Toyota’s Woven City of today. Verne applied electrical power for electrolysis to produce hydrogen fuel, power arc lighting, operate elevators, run cranes, open doors, and operate book lifts in library warehouses, as well as an array of time-saving electric devices. In his 1863 writing of his futuristic Paris, Verne’s problem was not the vision of an electrical Eden but how to supply the electricity needed for this Eden without the pollution of coal and steam. The electrical demands for Verne’s Paris skyscrapers needed lighting, powerful elevators, doors, and other electrical devices such as fax machines, copiers, calculators, and phones, which would be an enormous use of electricity. The primary electricity demand was street, business, and home lighting in Verne’s Paris.

In Paris in the 20th Century, Verne used the electric street lighting system known as the “Way Method” (after John Thomas Way), developed in 1860, which Verne referenced in Paris in the 20th Century (p. 24). The Way lighting system was an improved type of street lighting, a mix between straight arc and modern neon mercury lighting. Arc and mercury lighting brightness made it a poor system for room lighting. In Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1871), Verne noted that the harshness of early arc lighting had to be “softened and tempered by delicately painted [wall] designs” (Verne, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, p. 92). This harshness of the light was probably the reason some shopkeepers in Paris in the 20th Century rejected it and stuck with coal gas (p. 24). Brightness and feel remain a lighting problem and a source of green resistance even today. Verne used both arc and Edison’s softer incandescent lighting in his novel Underground City in 1877. Incandescent lighting became commercially available in the 1880s. Regardless of type, lighting requires a large amount of electrical power.

In Paris in the 20th Century, Verne was not clear on how massive amounts of electricity would be generated for urban use, but it would be the quest of his scientific novels to come. Still, Verne did not specifically name anyone one type of power source in his futuristic Paris, although he had noted many possibilities, which would be a life quest. Verne’s literary quest for mass-produced electricity took him over sixty novels and articles in four decades. Verne would explore improved batteries, solar, wind, hydroelectric, tidal, static electricity collection from the air, thermal gradients in oceans, and more efficient engines and motors.

Verne first looked to improve battery efficiency. When Verne wrote in 1863 of a futuristic Paris, unique and powerful chemical batteries for electricity were possible but far from feasible. In 1863, the only significant source of electricity was chemical batteries, but Verne’s Paris had twenty thousand street lights alone, which was beyond the scope of the chemical batteries of the 1860s.

Verne had followed the development of batteries from the 1840s, and Verne knew from the battery experiments of Davy and Faraday that batteries could not power a city of lights. Humphry Davy had established the cost of battery power, noting it in his arc lighting experiments in the 1820s. Davy required 2000 galvanic battery cells at six dollars per minute (about 200 dollars a minute today) to power one arc light. In 1848, two experimental arc streetlights in Paris were tried, which caused considerable excitement in Paris but was short-lived because of battery cost. Verne’s 20th-century Paris had 200,000 streetlights, and battery electricity would be cost-prohibitive. Verne would have realized that the future of electric cities would require mass production of electricity beyond the battery power of the 19th century, and this would be true even today with today’s powerful batteries.

Verne considered increasing the efficiency of batteries in his novels of the 1860s for more output. Verne tried to improve the common “Bunsen battery” in his 1863 novel Five Weeks in a Balloon. The Bunsen battery was a lead-carbon-acid battery.

Early in Verne’s Voyages Extraordinaire, Verne invented the most futuristic design of a sodium battery in Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea. Verne’s futuristic use of sodium was a hundred years ahead of its time and would significantly increase electrical output. This sodium battery has again taken Jules Verne into recent scientific headlines as a cheap replacement for lithium EV car batteries. However, Verne’s sodium battery would still require 500-1000 battery cells per single city street light in his futuristic Paris. Still in his Paris in the 20th Century, Verne applied smaller applications for batteries, such as powering musical instruments, but so much more power was needed.

Verne never wholly gave up on some role for batteries in his final fictional electrical city, Standard City in The Self-Propelled Island (1895); he sees our future of rechargeable batteries for electric cars, trains, boats, and small electrical devices.

Lighting homes, factories, shops, streets, and signs would require massive amounts of electricity. When Verne wrote Paris in the 20th Century, he did not specify how the enormous electrical power would be generated. Verne was sure that electrical generation would not be chemical-based but mechanical. In Faraday’s 1820s experiments, he generated electricity with cheaper mechanical magneto-electric generators (dynamos). Based on these early principles of electromagnetic induction, hand-cranked induction lanterns evolved in the 1840s, and Verne quickly realized its future potential. Verne used induction devices ( Ruhmkorff lamps) to generate electrical lighting in his novels Journey to the Center of the Earth (1870), From the Earth to the Moon (1865), and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1871). In his futurist Paris, he references the “Way Method,” which used a magneto-electric generator (a type of dynamo). Way used his system for a single lighthouse in 1858, but it was hand-cranked, hardly a system for urban lighting, yet Verne realized the potential for the future of a dynamo.

In 1858, the Alliance Company used a magneto-electric generator driven by a coal fueled steam engine to power arc lights and make hydrogen fuel through electrolysis; however, Verne’s own requirements in futuristic Paris was a very restrictive use of coal and steam. Eventually, in Verne’s novel The Underground City (1877), he applied the electro-mechanical dynamo generation for mass electricity. In Verne’s underground Coal City in The Underground City, Verne creates an electrical city using dynamos (“electromagnetic-mechanical machines”), and electricity is used for “all the needs of industrial and domestic life.”2 Coal City used electricity for lighting, ventilation, and heating. In one of his last books, The Self-Propelled Island, electro-mechanical dynamos would power urban needs. Verne was not as clear in Paris in the 20th Century, how massive amounts of electricity might be produced.

Power generation may have been generated by converting coal-fired steam power via a dynamo to electricity for Verne’s Paris. Of course, coal-powered dynamos were far from the green solution Verne wanted. Verne alludes to the green electromagnetic base by noting the Way Method. The Way Method dynamos were hand-cranked or gravity-based. Verne’s green Paris did have several other potential green power sources to drive a dynamo shaft or a magneto, such as wind, gas, compressed air, water power, chemical batteries, hydroelectric, and even hydrogen.

Verne had developed a vast windmill system in his futuristic Paris, which compressed air but could also turn a dynamo shaft (although he did not specify). Verne’s Paris had “1,853 windmills established on the plains of Montrogue” outside the city (Verne, Paris in the 20th Century, p. 24). Verne’s future Paris also had the potential for hydroelectric power, which Verne was using water turbines to replace waterwheel power in his green Paris. Since canals had connected Verne’s Paris to the ocean, there was even the potential to utilize tidal energy. His 1889 novel, The Purchase of the North Pole, notes the potential future of tidal power (p.16) France’s Rance Tidal Power Station was the world’s first large-scale tidal power plant, which became operational in 1966.

In the early 1900s, technology caught up with Verne’s imagination of clean electric cities. Verne would finally have a source for the massive electric needs of a city like his 20th-century Paris. Verne had long envisioned harnessing the power of Niagara Falls, which was achieved in the 1890s with hydroelectric power supplying factories in Buffalo, New York. In Jules and Michel’s novel, The Barsac Mission (1919), Verne’s imagination took these new power generation advances to build Blackland, a fictional city in the Sahara Desert. Verne had to evolve Blackland’s electrical power from wood-burning steam engines driving dynamos to green hydroelectric dynamos. Verne dammed the Niger River to generate electric power for his Blackland factories, city lighting, and irrigation system, declaring, “Smoke no longer gushes from the useless chimney.” This Vernian vision augured the 1930s Boulder Dam and Las Vegas system. Hydroelectricity is a significant electricity resource today, accounting for more than 16% of global electricity production.

Verne’s prediction of generating electricity from temperature gradients at different ocean depths is even more astonishing: “By establishing a circuit by wires at immersed at different depths, I will be able to generate electricity,” he wrote in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. Verne probably got the idea from Faraday’s thermocouple experiments, generating electricity from heat. Years later, in 1881, Jacques Arsene d’Arsonval, a French physicist, proposed Verne’s idea of tapping the ocean’s thermal energy. Still, this offered no solution to massive electricity production for a city; however, Verne might have been on to something. In 1970, the Tokyo Electric Power Company successfully built and deployed the first large-scale production using the principle.

Interestingly, Verne did not envision using solar energy to produce electricity and hydrogen, a recent area of significant research. Even though Jules and his son understood the principles of a photoelectric cell in 1888, it was a rarity that Verne so understood such a unique scientific discovery without extrapolating into the future.

Verne realized the issue was Victorian demand for heating, steam production, and industrial power produced from coal. Verne designed three great fictional electric-powered cities: Paris in Paris in the 20th Century, Standard City in The Self-Propelled Island , and Blackland in The Barsac Mission, which avoided or restricted coal-generated electricity. New Aberfoyle was an electric city but used coal to generate it (Underground City, 1877). Verne understood that the transition from coal would be measured in centuries, not decades.

Verne saw a 200-year struggle to reduce our dependency on coal and hydrocarbons. A reduction in coal smoke would be part of such a transition. Verne did not see a quick conversion from coal but looked to a gradual use of alternative energy, more efficiency, and even methods for the clean use of coal. As noted, coal gas production for home and street lighting was extremely popular because of its soft light. Coal gas production polluted the air, smoke, and rivers with benzene, chemicals, and tar. Verne also foresaw that there would be resistance to electric lighting and the green movement. He noted opposition to electric lighting in his future Paris by merchants who preferred the soft light of coal gas. Noting in his futuristic Paris, “Nonetheless a few old-fashioned shops remained faithful to the old means of hydro carbonated gas,” which necessitated “limited coal mining” (Verne, Paris in the 20th Century, p. 24).

Verne’s early writings noted that coal for heating and cooking was the primary source of Victorian air pollution. In his futuristic Paris, Verne used clean hydrogen for heating. In the same year, 1863, Verne used electricity for cooking in his Nautilus (Verne, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea).

Another possible interim reduction of coal pollution came in Verne’s Begun’s Millions, in which Verne envisions an environmental but dystopian city called France-Ville. As noted previously, Verne was concerned about unhealthy coal-burning air pollution. He feared government regulation would be needed in France-Ville. France-Ville used building regulations imposed on houses, and a unique subterranean scrubbing system was used to clean coal and wood-burning exhaust. The system took exhaust gases from the heating furnace via pipes to a “burner” used to strip it of carbon (Verne, Begum’s Millions, p. 124). While lacking the process details, it does augur today’s Clean Coal Technology.

Verne did look to cleaner petroleum as a possible fuel alternative. Verne foresaw petroleum’s potential, using it to fuel his floating island in The Self-Propelled Island. Verne compares petroleum to the “pollution” of coal-fired steam engines of the 1890s as “the difference being instead of black smoke, the chimneys emitted only light vapor that did not pollute the atmosphere” (Verne, The Self-Propelled Island, p. 41).

Figure 6 shows the original illustration from Verne’s novel Self-Propelled Island. Verne uses petroleum and/or petroleum biomass to heat steam boilers in place of coal which was then used to generate electrical power on his fictional floating island. In The Self-Propelled Island he describes the fuel as petroleum (p. 41) and “oil briquettes” (p. 55). Verne is using petroleum briquettes to replace coal to drive the steam engine dynamo and produce electricity. Verne predicts the future of petroleum briquettes based on some emerging technology and his imagination. Pressed palm oil briquettes were used in some countries in the 1890s for heating, but Verne used the word petroleum briquettes writing in 1895. Verne considered petroleum and/or petroleum products to be clean-burning fuels. Petroleum briquettes were just being experimented with in the 1890s but Verne recognized the potential.

Petroleum briquettes would have offered a deliverable product to Verne’s island in a world without oil tankers and a pipeline network. Verne states that petroleum briquettes are “less cumbersome, less dirty than coal, and have more heating power” (Verne, The Self-Propelled Island, p. 51). Amazingly, now 130 years later, petroleum briquettes are being looked at for the same attributes Verne noted. Research on petroleum and new patents for processing and chemical binders are emerging. The new look at petroleum briquettes lists similar advantages noted by Verne: ease of handling versus coal, its clean burning, heating power, and environmentally safe transportation. A recent study of biomass petroleum briquettes made from bitumen (raw petroleum), starch, and rice husks found that they are competitive in industrial heating (Ikell, 2014). A new patented process takes Canadian bitumen crude oil mixed with a polymer to form briquettes that can be transported without fear of spills or fires.

Petroleum oil, in general, emerged as a somewhat “cleaner” fuel by 1895; however, its refining was a significant pollutant by 1899. One of Verne’s fictional travelers in The Will of an Eccentric (1899) describes the oil refining atmosphere of Warren, Ohio, as a “sickening” atmosphere, tarry chemical water pollution and even explosive water pollution, which contributed to the famous 1969 burning of the oily Cuyahoga River in near-by Cleveland.

Unfortunately, Verne incorrectly wrote off natural gas as a clean alternative to coal in describing Pittsburgh’s still dirty air in The Will of an Eccentric (1899): “In spite of the thousands of miles of subterranean conduits by which natural gas is supplied.” Verne here alludes to George Westinghouse’s first massive conversion to natural gas from coal in Pittsburgh in 1887, using an enormous pipeline supply network. The use of natural gas dramatically reduced smoke, but supply diminished by 1892, and the coal smoke was returned by the writing of Verne’s The Will of an Eccentric (1899). Verne missed the actual improvement of natural gas conversion. The Society of Engineers reported: “We had four or five years of wonderful cleanliness for Pittsburg, and we have all had a taste of knowing what it is to be clean. We all felt better, looked better, and were better. But we are back into the smoke. It is growing worse day by day” (Tarr, 2015).

Verne’s other transitional strategy was improving the steam engine’s thermal efficiency, which was between 30 to 35 percent. The iconic Victorian steam engine was a major consumer of coal; therefore, efficiency improvements in steam engines offered significant reductions in coal pollution. Even today, coal, natural gas, oil, nuclear, and even some solar electrical plants use steam turbines with mediocre efficiencies. The major problem for Victorians was that the steam Rankine cycle has a 30-40 percent efficiency. In the 1860s, Victorian engineers and scientists pursued the use of carbon dioxide (they used the term carbonic acid) as a way to increase efficiency significantly. This breakthrough brings us to one of Jules Verne’s most obscure predictions in Paris in the 20th Century. Verne predicted that in 1960 Paris: “Carbonic acid (carbon dioxide) now dethroning steam” (p. 12). Later in the novel, he suggests the carbonic acid engine would power ships (p. 135). Verne again probably extrapolated Marc Brunel and his son Isambard ( Great Eastern fame) work in the 1860s, conducting over 15,000 experiments on a motor driven by carbonic acid (carbon dioxide) based on Michael Faraday’s theories.

In the late 1860s, James Baldwin detailed his patent for a carbonic acid engine using the physical phases (liquid and gas) of carbon dioxide at available temperatures and pressures in the 1860s. Such an engine was theoretically possible, but future engineering was needed for the super temperatures and pressures to make the engine cycle efficient. Steam turbines still produce over 75 percent of today’s electricity. Carbon dioxide engines have the potential for 60 percent thermal efficiency versus 35 percent for steam. This efficiency jump has led to a pilot plant using carbon dioxide in supercritical phases to replace steam. The Supercritical Transformational Electric Power project is one of the world’s largest-scale and most comprehensive, funded by the Department of Energy. A key project goal is to advance the state-of-the-art for high-temperature carbon dioxide in the power cycle performance. It may turn out that one of Verne’s little-noticed predictions will become one of his best.

Some of Verne’s visions of clean energy remain in the future. Verne envisioned a futuristic “accumulator” and “transformer” to gather static electricity from air or molecular vibrations. He describes these in his 1889 book, The Year 2889. In his 1885 novel Mathias Sandorf, he uses this Vernian accumulator for electric boats, and in Master of the World (1904) suggests their use to power electrical airships.

Conclusion

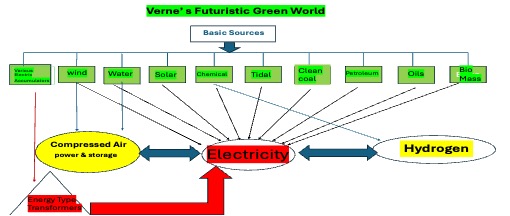

Figure 7 is a schematic summary of the fifty-year vision of Verne’s green future. It shows a mix of new sources for electricity, the need for storage, and a role for hydrogen.

The green design of energy started in his first novel, Paris in the 20th Century, which envisioned a green and cleaner city of the future. In it, Verne would design a green energy grid for his futuristic Paris and a blueprint to build on for his literary career. Verne then launched a 50-year literary journey of novels (Voyages Extraordinaire), which he improved on this initial urban energy plan. His futuristic Paris realized the potential of electricity in transportation, hydrogen generation, home heating, powering factories, and street lighting. Verne spent the next fifty years applying the evolving science to produce clean electricity in some of other his fictional cities. He foresaw the future of an electrical grid that could recharge battery-powered cars, trains, and electrical devices.

Verne saw a hydrogen-driven economy in the future, but the root of his economy was the electricity for electrolysis to produce hydrogen. His hydrogen solution evolves in four novels: Paris in the 20th Century, Five Weeks in a Balloon, Mysterious Island, and Dr Ox’s Experiment.

Maybe more interesting was Verne’s understanding of political issues and human resistance to change, which required some compromise as part of the solution. Verne articulated that the green transition would move slowly. Realizing that getting off coal required a transitional approach, such as his clean coal scrubbing system in Begum’s Millions. Verne looked further into the future need for efficient electrical devices, more efficient engines, rechargeable batteries, and energy systems as part of the big picture and longer-range solution.

Eventually, Verne would see the future in electricity, hydrogen, wind power, hydroelectric power generation, compressed air, biomass fuel, tidal power generation, and even solar power. Along the way, he envisioned an array of things like an electric submarine, an electric airship, electric vehicles, solar sails, high-speed pneumatic trains, hydrogen cars, hydrogen home heating, tidal wave power, windmills for electrical generation, and hundreds of futuristic devices.

Verne’s green vision is not complete, but we still have over 800 years to achieve Verne’s ultimate solution. In his book, The Year 2889, Verne hails the future of wonderful instruments, such as “accumulators”. Verne describes them as able to “absorb and condense the living force [energy from molecular vibration] contained in the sun’s rays; others, the electricity stored in our globe; others, again, the energy coming from whatever source, such as a waterfall, a stream, the winds, etc.” He, too, invented the “transformer”, a more wonderful contrivance still, which takes the living force [energy] from the accumulator and, on the simple pressure of a button, gives it back to space in whatever form may be desired, whether as heat, light, electricity, or mechanical force, after having first obtained from it the work required. The day when these two instruments were contrived is to be dated as the era of true progress. They have put into the hands of man a power that is almost infinite (Verne, In The Year 2889, pp. 21-22).

NOTES

- There are two translations of the Strand article one using 1000 and the other 1112 mph.

- Verne initially used hydrogen from the iron and acid chemical reaction to fill the balloon.

WORKS CITED

Bretwood, Higman, and Erin McKittrick, David Coil, “Quantifying Coal: How Much is There?” Ground Truth. 2019.

Butcher, William. Jules Verne: The Definite Biography. Thunder Mouth Press, 2006.

Cockburn, Harry. “Climate Crisis: UK’s Record Coal-Free Power Run Comes to an End.” Independent, June 2020.

Collins, Leigh. “Toyota to Mass-Produce Hydrogen Electrolysers in Partnership with Chiyoda.” Hydrogen Insight, February 5, 2024.

European Union News Letter. “Sustainability at One Franco-Chinese Month of Environment Gives Nod to Jules Verne’s Eco-Advocacy.” October, 2020.

Fouquet, Roger. “Long Run Trends in Energy-Related External Costs.” Ecological Economics 70, no. 12, 2011, pp. 2380-9.

Garfield, Leanna. “15 Remarkable Images That Show the 200-Year Evolution of the Hyperloop.” Business Insider, Feb 20, 2018.

Guess, Megan. “Canadian Plans to Transport Oil as Solid Briquettes Move Forward.” ARS Techinica, 2019.

Ikell et al, “Study of Briquettes Produced with Bitumen, CaSO4 and Starch Binders.” American Journal of Engineering Research (AJER), Vol. 3, 2014.

Jules Verne Forum, “Word Translation in Self-propelled Island.” Google Groups, 1/24/25 Jean-Louis Trudel to Quentin Skrabec.

Kham, Imram. Renewable Energy and Sustainability. Elsevier, 2020.

Minchinton, W. and Pohl, H. “ The Rise and Fall of the British Coal Industry: A Review Article.” VSWG: Vierteljahrschrift für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte, pp. 212-226.

Pacific Petroleum ed. “Petroleum Briquettes.” The Idaho Springs News, Vol xix, no. 33, Nov 15, 1901.

Rappe, Mollie. “Researchers Switch from Helium to Hydrogen Weather Balloons.” Sandia National Laboratories, May, 2023.

Ramirez, Vanessa. “Toyota Is Building a Futuristic Prototype City Powered by Hydrogen.” Singularity Hub, May 14, 2021.

Skrabec, Quentin. Green Friends: Henry Ford and George Washington Craver. McFarland,2010.

Taves, Brian. “Jules Verne’s Paris in the 20th Century.” Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 24, March 1997.

Tarr, Oel, and Karen Clay. “Boom and Bust in Pittsburgh Natural Gas History: Development, Policy, and Environmental Effects, 1878–1920.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. CXXXIX, No. 3, October 2015.

Urbinato, David. “London’s Historic ‘Pea-Soupers.’” US Environmental Protection Agency Journal, Summer 1994.

Verne, Jules. Begum’s Millions, originally published 1879, edited by Arthur Evans, translated by Standford Luce, Wesleyan University Press, 2016.

Verne, Jules, Paris in the 20th Century, originally published, Ballantine Books, 1996.

—. The Purchase of the North Pole, originally published 1889, Associated Booksellers.

—. Mysterious Island, originally published 1867, Kindle Edition.

—. Backwards to Britain, originally published 1859, Chambers Limited, 1992.

—. Five Weeks in a Balloon. 1863.

—. Underground City, originally published 1877, Luath Press, 2005.

—. The Will of an Eccentric. Sampson Low, Marston & Company, 1900.

—. The Self-Propelled Island, originally published 1895, translated by Marie-Therese Noiset, University of Nebraska Press, 2015.

—. Journey to the Center of the Earth. 1863.

—. Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea. 1871.

— and Michel Verne. In the Year 2889, originally published 1889, Seven Treasures Publications, 2008.

— and Michel Verne. “A Futurist Express Train.” Worlds Known and Unknown, The Palik Series.

Quentin R.Skrabec Jr. is a full-time researcher in engineering futurism, Jules Verne, Victorian science, the intersection of culture and engineering, and metallurgical studies. His education includes a BS in engineering from the University of Michigan, an MS in engineering from Ohio State, and a Ph.D. in manufacturing management from the University of Toledo. He has appeared on both PBS and the History Channel. He has published over 100 articles and 25 books in science, science fiction, and engineering.