⮌ SFRA Review, vol. 56 no. 1

Features

Jules Verne’s Fictional Quest for the Secrets of Krupp Steel

Quentin R. Skrabec

Story Summary

A French physician, Doctor Sarrasin, and a German scientist, Professor Schultze, inherit a vast fortune as descendants of an Indian rajah’s fortune. This rajah married the wealthy widow of a native prince, the “begum “ of the title. Each heir decided to build utopian cities in the United States.

Sarrasin builds France-Ville on the western side of the Cascade Range in the state of Oregon, with a focus on the health and wellness of its citizens. Schultze, a German militarist, builds Stahlstadt on the east side, a vast industrial and mining complex, devoted to the production of ever more powerful and destructive weapons. Schultze soon plans to destroy Sarrasin’s city.

Schultze builds an advanced steel mill for cannons. Stahlstadt becomes the world’s biggest producer of arms. Schultze was Stahlstadt’s dictator, whose very word was law and who made all significant decisions personally. Schultze was an eccentric and unusual character. Stahlstadt was an industrial and circular labyrinth covered in secrecy. The primary purpose of this cannon factory was to maintain secrecy around its advanced cannon-making process. It was strictly controlled by employees’ oaths, passwords, locked doors, guards, and a central observation tower. Schultze added a home in the middle, with exotic gardens and greenhouses.

Marcel Bruckmann, a friend of Sarrasin’s son, becomes an industrial spy to understand the manufacture and technology of Schulze’s cannons. Bruckmann relocates to Stahlstadt and quickly rises high in its rigid hierarchy, gaining Schultze’s personal confidence, spying out some well-kept secrets, and sending a warning to his France-Ville friends. Still, Bruckmann faces a factory built to maintain secrets and security. Schultze is not content to produce arms, but intends to use them first against France-Ville, then worldwide. Schultze’s super-cannon was capable of firing massive shells filled with gas. Schultze’s pressurized carbon dioxide gas was designed not only to asphyxiate its victims but also to freeze them. As Schultze prepares for the final assault on France-Ville, a gas projectile in the office accidentally explodes, asphyxiating him and leaving him in frozen animation. Stahlstadt goes bankrupt and becomes a ghost town. Bruckmann and Dr. Sarrasin’s son take it over. Eventually, Stahlstadt is re-invented as a peaceful manufacturing town.

Setting the Environment and the Story

In Verne’s scientific romances, science and technology are not merely a passive backdrop or setting for the story, but an active driver of the plot. Begum’s Millions1 (1879) is a prime example of this blending of technology and story; however, before examining the story of Begum’s Millions, there is a subject of debate, and we must first consider the authorship itself. Many consider Paschal Grousset (1845–1909) to be at least the co-author in the sense that many believe the story and framework were those of Paschal Grousset, and there is good evidence that Verne’s editor purchased the storyline (Verne, BM Luce ed, p. xvi). Indeed, there is support that the France-Ville of chapter 10 fits Grousset’s political ideas. Chapter 6, “The Albrecht Mine,” gives the reader the feeling of something patched in or merged from a different manuscript. Some merging and blending of two manuscripts was probably the case. As to Verne using Alfred Krupp and the Stahlstadt factory as a model for the book, there is a connection in Verne’s own words to his editor: “What shall we say about the Krupp factory now, as it is really Krupp who is in play here, and his factory that is so forbidden to indiscreet eyes.” (Verne, BM, Luce ed., p. 206, note 5)

Stahlstadt factory descriptions may have come from Victor Tissot’s The Prussians in Germany, published in Paris in 1876. Another possible source could have been a pamphlet published in 1865 by French science journalist and publisher, Francois Julien Turgan (Michaelis, 1888. P.50). Turgan documented the Krupp factory in Germany as well as other European cannon factories, focusing on its military artillery, design, and manufacturing processes. His account provides a detailed, illustrated record of the operations at Krupp during the mid-1860s. Napoleon III had planned to buy Krupp cannons in the 1860s, but the French military command overruled him. Everything changed with the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71), which started an international arms race.

Other sources could have been available to Verne, such as military reports from the 1870s, marketing materials from Krupp Steel, and those of French steelmaker Schneider-Creusot, which had a network of traveling engineers known as “Silent Research at Schneider” to study and report on steelmaking innovations worldwide. This is consistent with other sources available to Verne, such as military visit reports of the 1870s and the corporate spy network of the French Schneider Creusot steel. Verne’s story matches the unique actual process details of Krupp steel. The connections to some of Alfred Krupp’s personal characteristics are less compelling, but in the broader context of all the Krupp details, they rise above mere coincidence, and they should at least be discussed.

The Franco-Prussian War vividly demonstrated the superiority of Krupp’s breech-loading crucible steel cannons over the French’s muzzle-loading brass cannons. The world entered a type of arms race, which is reflected in Verne’s story. Herr Schultze’s steelworks and Marcel Bruckmann’s quest to uncover its secrets were based on the real international espionage by countries such as France and England to find the 19th century’s greatest industrial secret: the Krupp cast crucible steel cannon process.

Verne’s Cannon Factory Layout Versus Krupp’s

Verne was no stranger to iron works, forging, and cannon foundries, having visited the naval foundry and cannon shop near Indret a number of times with his father in his youth (Butcher, 2006, p.18). This cannon forge made use of steam forging hammers that Verne would write about in Begum’s Millions. Begum’s Millions demonstrated Verne’s depth of knowledge of the secretive Alfred Krupp and his factory. It is not fully clear how Verne acquired these details. The main source appears to be the secretive, partially published report of an 1865 visit to Krupp’s factory (Michaelis, 1888, p. 50). What is known is that Krupp’s layout of the factory and mansion is unique and far different than other steel works, such as Carnegie’s 1875 massive steelworks at Braddock, Pennsylvania, and France’s Schneider-Creusot. Both Verne’s and Krupp’s mills were built on a coal field with adjoining ore deposits.

Verne’s Herr Schultze’s city, factory, and castle reflected those of Alfred Krupp and the city of Essen. For study reference and comparison, Begum’s Millions Stanford Luce translation and William Manchester’s The Arms of Krupp will be used. Schultze, like Krupp, builds a massive tropical garden at the center of his factory operations around his factory home, which was unheard of until very recently, with roof gardens at manufacturing plants such as Ford Motor Company. Krupp had maintained his original family house of the 1820s amidst the works, adding gardens in the 1860s. However, in the 1870s, he built a castle overlooking the factory. Verne’s glass-enclosed heated garden was modeled after Krupp’s glass-enclosed gardens. In both cases, excess factory heat is used to maintain the temperature. Verne includes Krupp’s use of peacocks, pineapples, slag-formed fountains, and statues in the garden at the center of the steel works (Manchester, 1964, pp. 71-72). Verne’s Schultze had a museum and model shop exactly like Krupp’s, as described by a rare visitor to the works in 1865. Both Krupp and Verne had a tower with a glass lookout. Krupp’s original central home inside the factory had a glass “crow’s nest” for watching workers. Verne’s novel had the Tower of Bull at the center of Stahlstadt. Both used thick glass roof skylights.

Krupp’s steel works and mansion in the 1870s were described as: “The interior is a mad labyrinth of great halls, hidden doors, and secret passages” (Manchester, 1964. P. 110). This is a similar visual to Verne’s. Verne blends Krupp’s unique steelmaking process, industrial labyrinth, Krupp’s famous mansion, and passion for secrecy into his story. Krupp’s factory layout and restricted employee movement were core to his secrecy policy, which Verne illustrates in his story. Krupp’s Essen and Verne’s Stahlstadt are both integrated cities/factories. Verne’s Stahlstadt was modeled after Krupp’s factory, complete with a police force, guards at every department entrance, passwords, locked doors, codes, and secret agents (James, 2012, p. 42). Both factories were designed with circular-walled sections and locked departments to ensure no one could piece together the secret process of cannon-making, which was a key part of Verne’s storyline.

The fictional factory organization in Verne’s novel reflected the pioneering Krupp industrial philosophy of vertical integration, which involved owning and coordinating resources throughout the production cycle. Verne’s Stahlstadt, like Krupp’s Essen, was an oval-shaped city with a circular railroad to supply the steel works. While much is made of Verne’s circular steel city design on a philosophical, metaphysical, and mythical level, it appears to be inspired by Krupp’s “great circle railway” around his factory for process integration, allowing materials and semi-products to move between departments and connections to bring in coal and ore (Krupp Steel, 1912). William Kingston’s earliest English translation of Begum’s Millions, published in 1879, offers a slightly more explicit visual representation of this circular design. Krupp’s railway was built from 1874 to 1877 and was the subject of much news attention. The circular design enabled efficient integration, which other notable steelworks failed to achieve fully in the 1870s. All the great steel works of the 1800s and even the 1900s had a linear integration from department to department. It would be unlikely that Verne thought of this circular design independently of Krupp’s design. Interestingly, Verne would utilize this circular integration in his posthumously published novel, The Barsac Mission (1919), which featured an evil factory. The circular design of steel mills has become popular recently as the ultimate in vertical integration (IREA, 2023).

Making Steel in the 1870s: An Extraordinary Journey of Technology

The 1870s were a time of much innovation in steelmaking, particularly at Krupp Steel. Steelmaking was a matter of controlling carbon. Blister, puddling, crucible, open-hearth, and Bessemer converter processes were being used at various plants. Initially, Krupp used blister steel, as made in Verne’s novel Mysterious Island, as an intermediate step in making his crucible steel to cast cannons. But Krupp converted from blister steel as the intermediate step to puddling in the 1870s.

In Mysterious Island (1875),Verne clearly defines the metallurgical difference between blister and puddled process steel. Puddling allowed Krupp to move directly from pig iron to steel without producing the intermediate wrought iron product and then carburizing it in a cementation process to produce blister steel, as Verne’s island colonists did. After extensive trials, Krupp decided that a combination of puddled and crucible steel processes could meet the quality requirements of his cannons. Krupp also produced lower-quality steel for other applications using the Bessemer converter and evolving open-hearth steelmaking processes. In fact. Krupp had been the first to use the Bessemer process (1862) and the open-hearth process (1869). However, no other world steelmaker used Krupp’s combination of puddling and crucible processing for cannon steel because of the high cost of such double processing. Krupp believed that cost was secondary to achieving the best quality in the world. Verne captures Krupp’s quest for pride and excellence over cost in his character Herr Schultze. In 1875, Andrew Carnegie embarked on a journey to become the wealthiest man in the world, profiting from Bessemer steel in the mass steel market; however, Krupp remained loyal to puddling for his prized cannons.

The story of Begum’s Millions (1879) includes a fictional quest for Krupp’s secret steelmaking process. The quest evolved out of an international arms race that began with the American Civil War (1860-65) and the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71). In 1870, Schneider-Creusot began producing steel cannons using the Bessemer process, but never achieved the quality of Krupp’s cannons, and Schneider-Creusot lacked the puddling/crucible technology to match Krupp. To catch up, Schneider-Creusot developed a network of traveling engineers known as “Silent Research at Schneider” to study and report on steelmaking innovations around the world that could be applied to cannon making (Galvez-Behar, 2004). This research network encompassed patent office research, social networking at scientific meetings and conferences, and observations of competitive military cannon marketing trials, as well as visitors’ notes from competing steel mills. Krupp was forced to balance the secrecy of his superior process with the need to utilize it as a marketing tool for the global market. In 1878 and 1879, Krupp held competitions known as Völkerschiessen, which were firing demonstrations of cannons for hundreds of international buyers to view his operations. Being aware of the Schneider-Creusot spy network, Krupp would not allow French observers.

The success of Krupp’s famous cast crucible steel process was a complex evolutionary process and technological innovation. The basic core crucible process developed by Frederick Krupp (1787-1826) evolved throughout the 19th century under Alfred Krupp (1812-1887). Interestingly, Alfred Krupp has been accused of stealing the original basic crucible steelmaking process from Britain in the 1850s. (Stewart, 1994) The Krupp cast crucible steel process was a mix of crucible steelmaking, puddling, and advanced forging techniques.

The process outline consisted of producing high-quality pig iron from a blast furnace. The process outline consisted of producing high-quality pig iron from a blast furnace, remelting this pig iron in a puddling operation to make steel, then forging and rolling rods, remelting pieces of these rods in multiple crucibles, and finally sequencing the casting of steel blocks to be forged into cannon barrels. Originally, Krupp exploited blister steel production on a massive scale to maintain the quality of its cannons. Krupp switched to puddling only after years of testing in the 1870s.

Krupp’s cast crucible steel of the 1870s for cannons was unique among other steel processes and cannon makers. Most militaries of the world were still using bronze and cast iron, which could be cast directly into a cannon body. At the time, steel could not be cast directly into a quality cannon body. The term “Krupp cast crucible steel” can be misleading since cast steel blocks were forged into a cylindrical cannon body. The secret of Krupp’s process lay not only in the chemical processes but also in his forging operation, which utilized steam hammers. By today’s standards, the Krupp process was redundant and seemingly endless, with melting, reheating, rolling, hammering, and final forging stages. At the same time, Krupp was pioneering newer steel processes of Bessemer and open-hearth for other products, such as railroad rails and wheels, and plate armor, but never his cannons in the 1870s.

Mass steel production using puddling instead of the newer, cheaper processes of Bessemer and open-hearth was unique to Krupp’s cannon making in the late 1870s. His major competitors in France, England, Russia, and America were using the Bessemer process and moving toward open-hearth manufacture. One of the reasons was that Krupp’s iron sources were high in phosphorus, which embrittled steel, and Bessemer and open hearth at the time were not efficient at removing phosphorus, while puddling was.

A Krupp cast crucible steel cannon was the most feared worldwide because of its accuracy and range. Steelmaking, steam hammer forging, rifling, and breech loading were the four key factors contributing to the field superiority of Krupp’s cannon. Verne knew the superiority of Krupp’s crucible steel cannons through the Paris bombardment and France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71).

In Verne’s Mysterious Island (1874), he highlights the cast steel breech-loading cannon but does not use the Krupp name (Verne, Mysterious Island, p. 482). In Begum’s Millions, Verne highlights this revolutionary breech-loading design and rifling, which was the signature design of the Krupp cast steel cannon (Verne, BM, p. 97).

At the time, Krupp’s cast crucible steel process was the biggest industrial secret in the world. One exhaustive study of the Krupp crucible cast steel showed that the full details of the Krupp process are still not fully understood (Barraclough, 1981). In Begum’s Millions (1879), Verne deals with the details of the casting of crucible steel. Verne features Krupp’s metallurgy and methods in 1879, a remarkable literary and research achievement.

The real historical stories of the quest to find Alfred Krupp’s secretive cast steel process were as fascinating as Verne’s fictional. The story of a spy in Begum’s Millions, Stahlstadt reads like the real-world struggle of competitors and their spies trying to discover Krupp’s secret process. Alfred Krupp required loyalty oaths from his workers, who were confined to their departments to prevent them from learning the overall process (Manchester, 1964, p. 157). Krupp maintained a large plant police force, posted guards between sections, and had roaming plant agents. Rarely was a worker transferred to a different department without demonstrating extreme loyalty. All of these are characterized in Verne’s novel. Krupp employed spies to watch his workers in the mill. If a worker left for another company, Krupp spies would follow. Surprisingly, Verne missed Krupp photographing employees for identification. Krupp used photography to collect engineering data on the competition at artillery exhibitions. Krupp also personally orchestrated and approved process photography at his own exhibitions for marketing and international expositions (Bosson, 2008).

Even today, the whole secret of cast crucible steel is not fully understood. Verne’s description appears to have an origin at least partially based on unauthorized notes from a French science editor who visited Krupp’s factory in 1865 (Michaelis, 1888. P.50). Verne described the same sketchiness as the published unauthorized tour notes of 1865 and 1888. It appears that when Krupp granted tours, they were purposely disorganized or organized to limit a complete understanding of the process. In 1878, Krupp hosted a special tour of military experts to help improve international business, but no French officials were allowed in (Menne, 2013, pp. 110-114). There doesn’t appear to be any detailed records of this 1878 tour until 1888.

Krupp and Verne’s Schultze Cannon Making

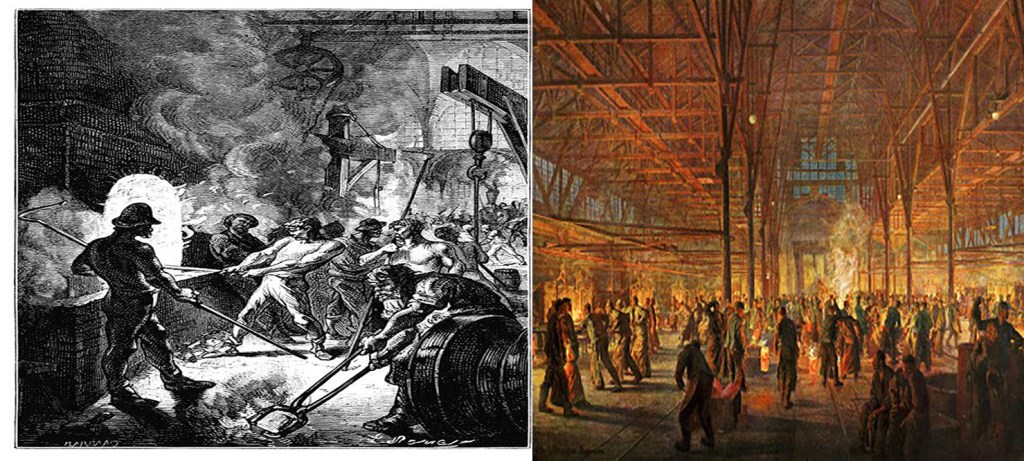

The secret cannon-making required a complex factory of ironmaking, steelmaking, and steam-powered forges, presses, blooming mills, and rolling mills, not something Verne could have easily put together without detailed information. The reconstructed description by Verne of the Krupp process for high-quality cannon steelmaking steps was detailed in Begum’s Millions (1879). Verne’s literary technique to probe the secrets of the process was the search by a spy, Marcel Bruckmann, who was planted in Stahlstadt to find the secret. Verne’s spy takes samples of ore, steel, and slag while taking notes on the process. Verne’s spy espionage begins in the puddling section.

Verne applies puddling, a unique feature of the Krupp process at the time. Without Verne trying to emulate the Krupp operation, it would be unlikely for Verne’s fictional design not to incorporate the emerging Bessemer and open-hearth processes used in France, England, and America. There is an unusual connection between Krupp and Verne’s understanding and use of puddling. Verne’s spy Marcel Bruckmann describes puddling, mentioning the use of “Chernoff’s rules,” a scientific detail that few would have known in 1879, except for metallurgists in Russian and German steelworks. Chernoff is clearly a misspelling or translation issue of the Russian metallurgist Dmitry Chernov. Chernov, in 1868, after studying the production of heavy guns at Obukhovsky Steel Foundry, published a paper in Russian on the necessary temperature control in puddling furnaces. The 1869 publication of this article is considered the date of the transformation of metallurgy from an art into a science (Golovin, 1968, pp. 335-340). It was translated into English and French in 1877.

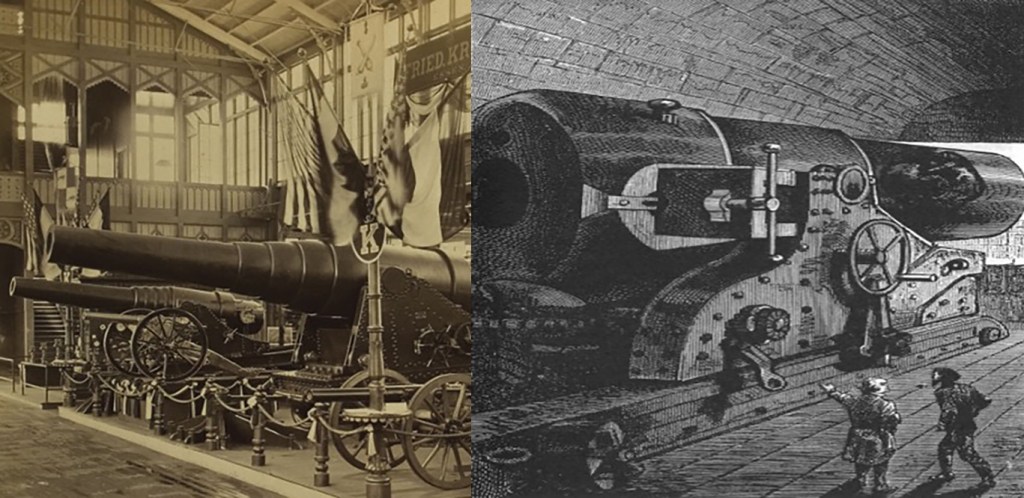

The exchange of technology between Russia and Krupp was a mix of formal and informal exchanges (James, 2012, pp. 49-50). Since the 1860s, Russia had been the largest customer for Krupp, thereby granting the company access to its operations. One of Krupp’s significant advances in cannon making, which involved overlapping tube barrels as seen in Begum’s Millions’ illustrations, came at the insistence of Russian military engineers (Krupp Steel, 1912, p. 124). At the same time, Russia was determined to become independent of German cannons and had assembled a research center of the best metallurgists, similar to the Schneider-Creusot network. Krupp had its own counterpart spy group of metallurgists in the 1870s, which traveled around the world to monitor competitors (James, 2012, p. 45). Krupp had applied this Russian science to achieve exceptional quality. Verne demonstrates his understanding of the process and the science and metallurgy of puddling, such as temperature control, as seen in Begum’s Millions.

Puddling offered a quality steel to feed Krupp’s crucible furnace operation for massive cannons. Puddling is the process of converting pig iron to steel in a coal-fired reverberatory furnace. It was a labor-intensive process of hammering pasty iron balls into steel.Puddling was hard work, as Verne described using his spy character in Begum’s Millions. The problem was thatpuddling is limited to a direct and consolidated steel billet, typically ranging from 1 to 2 tons.Puddling could not directly produce a 330-ton batch of steel needed for Schultze’s cannon. This is where the Krupp crucible process was key. Puddled steel had to be remelted in crucibles to consolidate the homogeneous quantity of steel for cannons.

The puddling steel product required batches to be hammered into blooms and billets, and then rolled out into rods. These puddled rods were broken into pieces and packed into crucibles. For this part of the process, Verne’s description of packing the crucibles is somewhat lacking, but the melting and casting of these crucibles captures Verne’s full attention. Verne is amazed at the German precision of this part of the process. German precision was the heart of Krupp’s success in cannon making.

It took many crucibles of remelted steel to make cannons of 20 to 40 tons, the typical weight of Krupp’s 1870s cannons. These crucibles had to be blended into a large molten steel bath by simultaneously pouring them to produce large, homogeneous steel blocks to make cannons. The blending was done by pouring the crucibles into a clay channel that led to the ingot mold. In the 1850s, Krupp Steel developed timed simultaneous mixing and casting of many crucible furnaces, allowing for the homogeneous quantity of steel needed to make steel cannons. In his 1870 novel From Earth to the Moon, Verne uses the Krupp precision simultaneous discharge of 1200 furnaces to cast his gigantic 68,000-ton iron moon cannon.

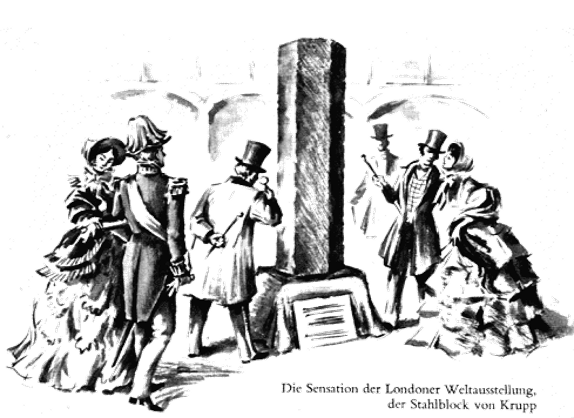

Many recall Krupp’s famous Great Exhibition of 1851 exhibit of steel cannons, but for engineers, it was not cannons that amazed but the largest steel ingot ever cast up to that point, weighing 4,300 pounds (approximately 2,000 kg), achieved with the simultaneous casting of 98 crucibles.

Ironically, Krupp would exhibit a steel ingot of double the size, earning a gold medal at the Paris Exhibition of 1855. Krupp’s success led to the world’s largest and most powerful cannons, which would rain shells on Paris in 1870.

The Krupp cannon exhibited at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition weighed 122 tons. Krupp’s 1892 cannon was 150 tons. Verne uses several pages to describe this precision casting method applied to crucible steelmaking in Begum’s Millions; Schultze’s cannon was 330 tons in Verne’s 1878 novel.

The final operation was forging the cannon from the cast steel block into a finished cannon cylinder. Krupp was the first to forge seamless tubes in the 1850s. Forging was required in the cast-crucible process to break up the cast steel microstructure, thereby reducing the fracture risk and improving strength. Forging was also a critical part of Krupp’s superiority in cannons.

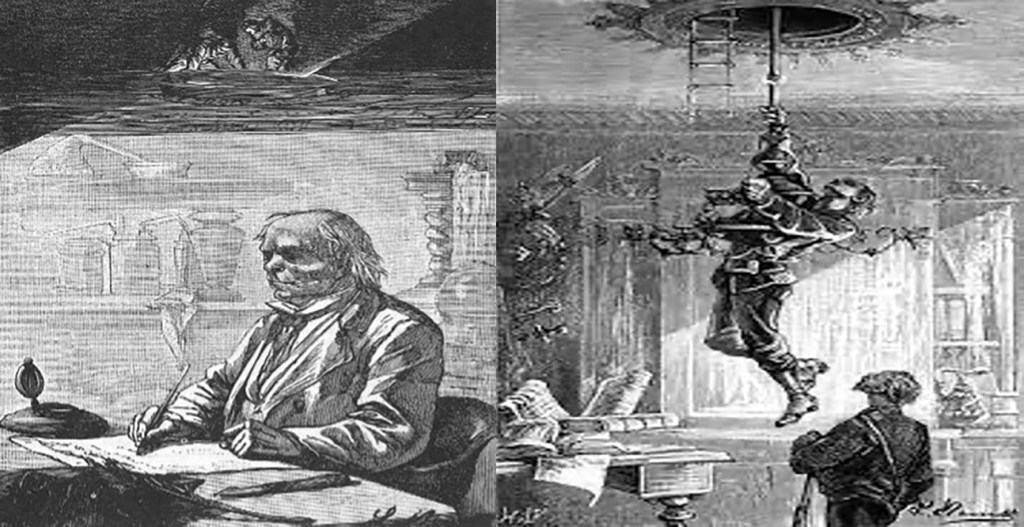

Part of Krupp’s secret was upset forging of the steel block into cylinders by steam-powered presses and forging machines. A hole was drilled into the steel block and then forged with a cold mandrel. Krupp would build the world’s largest forging hammers. The length of Krupp’s cannon required several cylinders to be shrunk and forged to fit together, and this can be noted in the illustrations used in Begum’s Millions. Russian engineers had suggested this cylinder built-up of the cannon, but Krupp applied it and perfected it in the 1870s. Verne captures another advantage of Krupp’s cannon-making in his steam hammers for forging. Krupp built hundreds of steam hammers to forge his cannons and sell hammers around the world. Krupp maintained a huge drafting (engineering) department to improve its products continually. Verne’s novel reflects this when his spy gets stuck in Stahlstadt’s engineering department, designing endless types and sizes of steam hammers (Verne, Begum’s Millions, 1879, p. 83) Finally, there were intermediate annealing steps and a final machining for a rifled barrel and placement of his patented breech-loading system.

Interesting Comparisons: Schultze versus Alfred Krupp

The political subplot and literary imagery of Begum’s Millions have been discussed by several reviewers, and it makes for a fascinating study. Still, Krupp’s own personal struggles may be just as important and more interesting. Recent reviews feel that the character of Herr Schultze is clearly modeled after Alfred Krupp.2 This effort focuses on looking at Alfred Krupp (1812-1887), his company Krupp Steel, and his steel city of Essen as a model for Herr Schultze and Stahlstadt. Verne’s technical depth of the secret of Krupp cannon production is impressive, but just as important is his knowledge of Krupp the man. Krupp was known as an eccentric with a “slew of anxieties: hypochondria, insomnia, and a phobia of everything from fire to suffocation from his own bodily gases” (Dirada, 2006, p. BW15).Verne also reveals his knowledge of the personal and operational functioning of Krupp Steel in the late 1870s. Finally, he knows Krupp, the man, and how he runs Krupp Steel. Verne had clearly studied Alfred Krupp, his factory, his steel city, Essen, and the Krupp Castle. Verne demonstrates his understanding of Alfred Krupp’s idiosyncrasies and personal events, which he incorporates into the story.

When Verne’s spy Bruckmann breaks into the frozen office of Schultze, he notes the electric light, but also notes a large candelabra. This again was an eccentric characteristic of Krupp, who used only pure tallow candles to light his living quarters, fearing suffocation by gas, which was the standard lighting vehicle in 1879. Such comparable details in Verne’s led to other possible plot items that might be considered coincidental except for the number of Krupp details already noted.

One interesting possibility is the incorporation of Krupp’s fear of asphyxiation by carbon dioxide in Verne’s novel. Krupp hated drafts, so he permanently closed windows, requiring him to build a special ventilation system for his castle. Still, Krupp came to believe that his ventilation system could not prevent the buildup of carbon dioxide. Krupp was a hypochondriac who was said to “be a night ghost hunting his castle sniffing for traces of carbon dioxide” (Manchesster, 1964, p. 140). While Alfred Krupp did not die of asphyxiation, Verne’s Herr Schultze would die from carbon dioxide asphyxiation. This accidental asphyxiation of Herr Schultze was a result of the plan to use a mass destruction cannon shell using carbon dioxide asphyxiation on his rival city of France-Ville. In an earlier chapter, a thirteen-year-old child died from carbon dioxide asphyxiation because of a poor mine ventilation system, and later, Herr Schultze threatened to asphyxiate a spy while he slept.

Chapter 15, “The San Francisco Stock Exchange,” feels that it was adapted, modified, or added to the original manuscript. Yet it accurately mimics the critical period of Alfred Krupp’s life during the international financial and stock market Panic of 1873. Verne sets up the financial and stock market crisis of chapter 15 as “a natural consequence of… this concentration of all power in one person” (Verne, Begum’s Millions, 1879, p. 156). Schultze’s greatest fear, like Krupp’s, was to lose control of his company. Krupp’s sole ownership led Krupp Steel to the brink of bankruptcy in the mid-1870s. A depressed Krupp took his exit from the public to avoid reporters. Like Schultze, Krupp was involved in a possible Central Bank takeover. Krupp could not get bank loans until a banking association was formed with the government’s help to save him. Krupp was forced to sign a “shameful” document that required some sharing of authority among the company bankers (Manchester, 1964, p. 140-150).

The literary image of the novel’s guarding giants, Arminius and Sigimer, has been studied, and their link to mythical characters and German politics has been noted. Additionally, they reflect the company police force of Alfred Krupp, which was used to guard the manufacturing secrets and maintain order and adherence to Alfred Krupp’s company rules.

With the organization of Stahlstadt’s steel factory, Verne again demonstrates an extensive knowledge of Krupp’s factory in the 1870s. Most of Verne’s organizational description of the Stahlstadt appears to have come from Krupp’s General Directive of 1872. Many of these details were unique to Krupp’s Essen operation. Verne, like Krupp, uses sectors (departments) and shops for operation layout and a hierarchy of foremen, section chiefs, and directors, as well as using military ranking. More interesting is the role of the foreman in the organization, which reflects the changes at Krupp in the 1870s. Krupp thus started to use the foreman as an integral part of the organization in the 1870s. Verne incorporates the employee development role of the foremen in the story to allow his spy to be moved from the department and promoted up the hierarchy (Verne, Begum’s Millions, 1879, pp. 58-84). Verne was also aware of Alfred Krupp’s unusual hybrid hierarchy of civilian titles and military ranks, as noted in the promotion of his spy, Marcel Bruckmann, to lieutenant in Chapter 7 (Verne, Begum’s Millions, 1879, p. 82).

The story also reflects the arms race and the French fears of Germany. The France-Ville, in Chapter 10, was probably written by Paschal Grousset (1845–1909) rather than Jules Verne. Translator Stanford Luce references a letter from Verne to his editor stating: “I don’t see any differences between the city of steel and the city of well-being” (Verne, Begum’s Millions, 1879, p. 213, note 1). It was probably Verne who emphasized the government’s control of living regulations in France-Ville in the chapter for contrast, suggesting there was little difference between the paternalism of Krupp and the totalitarian application of social democracy, which Verne portrayed as feudal. Of course, France-Ville was truly a socialist state with a free health system, free healthy activities, and restrictive government regulations to control environmental issues such as smoke, which reflects Grousset’s political view, but Verne’s political view is more moderate. Verne had, early on in his 1863 novel Paris in the 20th Century, presented a similar mixed political approach.

While many see Begum’s Millions as a conflict between France and Germany, which certainly fits well, Krupp’s writings, employee edicts, and documents addressed the comparison between social democracy, which was gaining traction across Europe, and his own counter-philosophy of paternal capitalism. This narrative would also reflect Verne’s fictional struggle between France-Ville and Stahlstadt. Krupp’s paternalism is evident in Verne’s Stahlstadt, as seen in employee technical training, paternal care by foremen, pensions, and family employment, all of which were practiced by Krupp.

Another Schultze-Krupp comparison is the use of disabled workers. When Marcel Bruckmann comes to enter Schultze’s central living area, Verne emphasizes that the guard was “an invalid with a wooden leg and a chest full of medals” (Verne, Begum’s Millions, 1879, p. 53). Not surprisingly, Alfred Krupp was a national advocate of employing disabled veterans of the Franco-Prussian War. Krupp, in a letter, asked for disabled veterans to be hired so they are not “supported like beggars” using government charity (Berdrow, 1930, p. 267). This type of government unemployment benefit was at the heart of social democracy. Krupp was known in Germany for assigning any disabled or injured employee to light-duty jobs.

In reality, Krupp’s paternal organization had characteristics of both Verne’s Stahlstadt and France-Ville. Krupp provided extensive educational benefits, low-cost housing, medical care, and pensions. The difference was in the delivery to the workers (socialism versus paternalism).

Areas of Future Research and Analysis

Verne’s demonstration of his knowledge of Krupp’s metallurgical process and Krupp’s personal behavior suggests a possible deeper presence of Krupp in Begum’s Millions. Many have viewed the novel as a comparison between the dystopia of Stahlstadt and the more utopian model of France-Ville. Others have seen it as the arms race and political struggle between France and Germany. If you look at the novel through the eyes of Alfred Krupp of the 1870s, other themes emerge. Germany of the 1870s was like the rest of Europe, struggling with social democracy and Marxism, and Krupp’s own factory was no exception. Marxists were actively trying to win over Krupp’s workers. Alfred Krupp was passionate about stopping the rise of social democracy in Europe and Germany, a sentiment that is evident in the story. Certainly, France-Ville could also have represented the social democracy movement. Krupp published numerous letters to his employees and to the rulers of Germany on this matter. Alfred Krupp’s address to his employees on February 11, 1877 might well explain the struggle between France-Ville/ Sarrasin and Stahlstadt / Schultze portrayed in the novel (Krupp, 1877, GHDI). Also in the 1870s, the world was locked in a struggle for control of production, as reflected in the rise of socialism and capitalism.

Herr Schultze demonstrates the biggest fear of capitalists worldwide: the loss of control over production. In America, renowned steel titans such as Andrew Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick were frequently criticized for being greedy and anti-union (Skrabec, 2012, p. 21). However, like Alfred Krupp, the real story of opposing unions was not so much about money as it was about control over how the factory was run. In this respect, these capitalists, like those in Verne’s fictional world, feared unions, shareholders, and bankers alike. In this, their paternalism was an effort to gain loyalty. There is much material in Begum’s Millions to explore this basic premise further.

Verne’s description of Schultze does present him as a fearful, even evil, man. However, in describing France-Ville, the reader gets a sense of a very rigid approach, where the government knows best, reminiscent of Krupp’s criticism of social democracy. There are also hints of some of the positive aspects of Krupp’s competing ideal of paternal capitalism, such as education and a paternal approach to employees. In a way, both models are feudal in nature. A view of the novel might consider the story not only as a comparison but also as an exploration of how the two political approaches might be merged for the common good, as Verne suggests in the ending.

Conclusion

Verne borrowed heavily from Aldred Krupp and his steel town in writing Begum’s Millions (1879). Much of the storyline and subplots can be linked to the Krupp legacy, such as competitors’ industrial spying, plant layout, company secrecy methods, European paternalism, the rise of social democracy and Marxism, and technological advances. A major subplot involved an industrial spy’s search of Herr Schultze’s steelworks, which was based on the real international espionage by countries such as France and England to uncover the 19th century’s greatest industrial secret: the Krupp cast crucible steel cannon process. Verne’s description of the secret crucible steel process was visionary and well researched for the state of public knowledge in the 1870s. There are also interesting comparisons and potential connections between Schultze and Alfred Krupp for further research.

NOTES

- The most common title used is Begum’s Fortune, however it was first published as 500 Millions of the Begum. I have chosen the title Begum’s Millions to use because the Luce’s translation is what I used as a base for comparison.

- Review by Michael Dirda, Washington Post, Sunday, March 5, 2006; Page BW15.

WORKS CITED

Barraclough, Kenneth. “The Development of The Early Steelmaking Processes: An Essay In The History of Technology.” Thesis submitted to the University of Sheffield, 1981.

Berdrow, Wilhelm. Krupp: A Great Business Man seen Through His Letters, The Dail Press, 1930.

Bossen, Howard, and Eric Freedman, Julie Mianecki. “How Photographers Gain Access To Steel Mills.” Vira, 2008.

Butcher, William. Jules Verne. Thunder Mouth Press, 2006.

Carter, Elliot. “Villa Hugel: The Monumental Home of Prussia’s Eccentric ‘Cannon King.’” Atlas Obscura, 2017 .

Dirda, Michael. Washington Post, Editorial Sunday, March 5, 2006; Page BW15.

Galvez-Behar, Gabriel. “Technical Networks at Schneider.” Business and Economic History On Line, Vol 2, 2004.

Golovin, A. “The Centennial of D. K. Chernov’s Discovery of Polymorphous Transformations in Steel 1868–1968.” Metal Science and Heat Treatment, vol. 10, no. 5, May 1968.

James, Harold. Krupp: A History of the Legendary German Firm. Princeton University Press, 2012.

IREA. “Towards A Circular Steel Industry, International Renewable Energy Agency.” 2023.

Krupp, Alfred. “Address to his Employees (February 11, 1877).“ German History in Documents and Images.

Krupp Steel. Krupp: A Century’s History of the Krupp Works, 1812-1912. Org. 1912, reprinted Legare Street Press.

Manchester, William. Arms of the Krupp. Little, Brown and Company, 1964.

Menne, Bernhard. Blood and Steel – The Rise of the House of Krupp, Menne Press , 2013.

Michaelis, K. and E. Monthaye. Visit to Krupp Works. Leopold Classic Library, 1888.

Skrabec, Quentin. Benevolent Barons: American Worker-Centered Industrialists, 1850-1910. McFarland, 2012.

Stewart, Philip. “Role of the U.S. Government in Industrial Espionage.” 1994 US Army Executive Research Project

Tissot, Victor. “The Prussians in Germany.” 1876.

Verne, Jules, Begum’s Millions, originally published 1879, translated by Stanford Luce, Wesleyan University Press, 2005.

—. Correspondance Inédite de Jules Verne et de Pierre-Jules Hetzel, 1 sept. 1878.

— Mysterious Island, originally published 1874, translated by Sidney Kravitz Wesleyan University Press, 2001.

Waltz, George. Jules Verne: The Biography of an Imagination. Henry Holt and Company, 1949.

Quentin R.Skrabec Jr. is a full-time researcher in engineering futurism, Jules Verne, Victorian science, the intersection of culture and engineering, and metallurgical studies. His education includes a BS in engineering from the University of Michigan, an MS in engineering from Ohio State, and a Ph.D. in manufacturing management from the University of Toledo. He has appeared on both PBS and the History Channel. He has published over 100 articles and 25 books in science, science fiction, and engineering.