Non-Fiction Reviews

Review of Hollywood’s Monstrous Moms: Vilifying Mental Illness in Horror Films

Shiqing Zhang

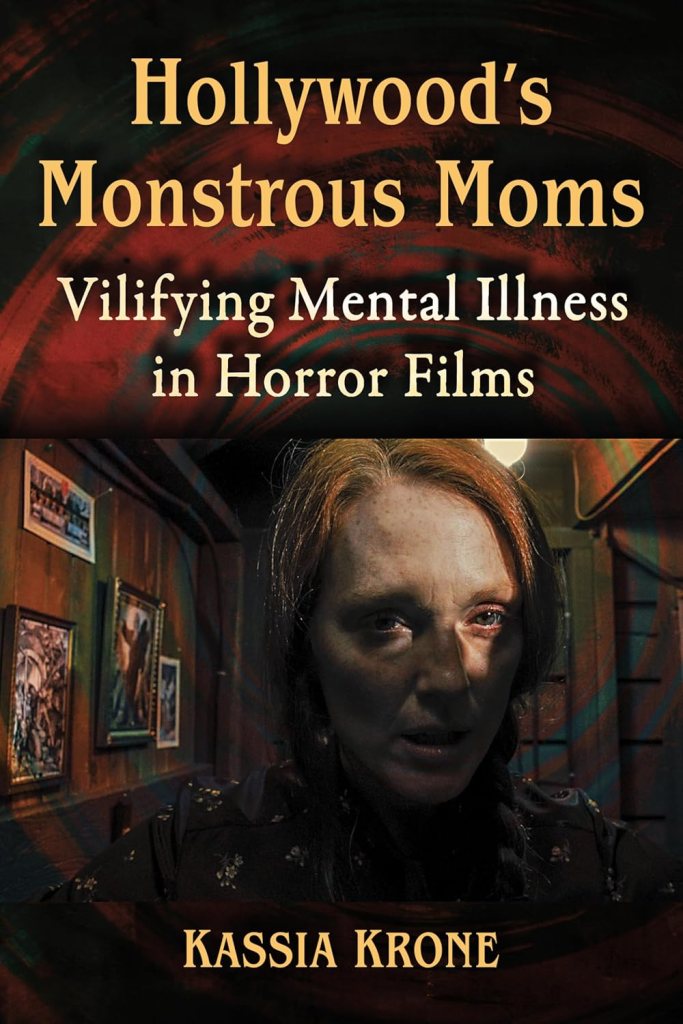

Kassia Krone. Hollywood’s Monstrous Moms: Vilifying Mental Illness in Horror Films. McFarland, 2024. Softcover. 209 pg. $55.00. ISBN: 9781476688930. eISBN: 9781476652337.

Kassia Krone’s Hollywood’s Monstrous Moms exposes the long-term stigma against mothers with mental illness in Hollywood horror films. Her study demonstrates a troubling pattern in the film industry of villainizing mothers with mental illness. Her book also identifies a research gap that hasn’t been fully explored at the intersection of disability studies, women, and mental illness. Disability studies in film has increasingly focused on representations of physically disabled bodies, arguing that their representation challenges the dominant able-bodied cinematic narrative. While there is some attention to cinematic characters with mental disorders, the one-dimensional characters make the discussion lack complexity. Even within feminist disability studies which critically examine the stereotypes about women with disabilities, women with physical disabilities or chronic illnesses are often central in discussions about the female body, beauty standards, and medical treatment as opposed to the experiences of women who are mentally ill. However, Krone’s research follows a feminist approach while adding the focus on mental disabilities.

The scope of Krone’s research includes classic horror films such as Carrie (1976), Mommie Dearest (1981), and Rosemary’s Baby (1968); slasher films such as Friday the 13th (1980) and Scream 2 (1997), as well as other more recent films such as The Sixth Sense (1999), Us (2019), Things Heard & Seen (2021), and so on. Her research also examines prestige horror films such as Hereditary (2018) and The Babadook (2014) to address the new trend. Krone’s scope is large, but all these films portray women with mental illness, which also illustrates how their images are rendered as a horror trope by the film industry. As Krone argues, these tropes vilify disability and gender together, especially motherhood. These depictions are also harmful to those in the disability community who fight for justice and equal rights.

Krone mainly examines female characters with mental illness from the following perspectives: women’s liberation movements and the film industry backlash; the representation of disability tropes; medical and social models of disability; and mother-child relationships. This approach draws her research into conversation with the gender inequality in Hollywood, disability tropes in films, and the narrative of female madness. Dating back to the Victorian period, women with mental illnesses were viewed as moral failures or as inherently emotionally fragile, which successfully constructed female madness as something stigmatizing and distorted. Krone’s analysis persuasively argues that these discriminations are also ubiquitous in contemporary cultural products.

Chapter One discusses classic horror films such as Carrie, Rosemary’s Baby and Mommie Dearest, in which mentally ill mother characters serve as a horror response to the emerging independent women. Their mental illness is used as a metaphor for punishment, suggesting that their progress is “detrimental to their mental health or stability” (22). Chapter Two analyses the films The Others (2001), Mama (2013), and Things Heard and Seen to illustrate how mental health facilities or haunted houses impact women’s mental condition and dehumanize them. This discussion is also addressed to the history of women who are diagnosed with hysteria, showing the long history of the medical narrative inclined to stigmatize them as ‘mad women’ without questioning the reason and truthfulness and then imprison them into isolated spaces (45). In these films, these female characters become ghosts after their suicide and haunt their children in the house. These depictions also complicate Jay Timothy Dolmage’s “kill or cure” trope for disability representation in film, as these mentally ill women “are already dead” and need to be banished again (57). Chapter Three focuses on the female killers in the slasher films Scream 2 and Friday the 13th. They are labelled as psychotic, driven to seek revenge for their sons’ death, a characterization reinforced by the slasher film narrative to emphasize their ‘craziness’ while ignoring their grief and emotional trauma over losing their children.

Moreover, these harmful portrayals are also linked to other forms of discrimination, such as racism and medical bias. Krone’s discussion situates these elements within the concept of intersectional feminism, which recognizes overlapping oppression rather than focusing solely on sexism. Chapter Four shifts the focus to mentally ill Black women in the horror films Ma (2019), Barbarian (2022), and Us. Even when Black women are present, the film industry often commodifies them through fixed tropes or stereotypes, such as the “Black villain” (96) and the “Black female vixen” (97). Their mental health is often overlooked by medical professionals and the film narrative, especially when they encounter racism and ableism at the same time: “blackness” is sometimes regarded as a form of disability within horror film narratives (108). Chapter five discusses the representation of mothers with Munchausen syndrome by proxy (MSP) in films The Sixth Sense, Fragile (2005), Love You to Death (2019), and Run (2020). It is implied that mothers who have mental illnesses are unfit to raise children.

However, this does not mean that all contemporary horror films are trapped in this representational dilemma. As readers might be aware, horror films are also constantly evolving, responding to the growing concern regarding approaches to disability and gender. Krone examines Things Heard and Seen in Chapter Two to argue that it provides an unconventional ending that resonates with contemporary feminist movements by foregrounding female solidarity. The film emphasizes the collaborative efforts among spectral moms to break the cycle of domestic abuse. Chapter Six shows that Hereditary and The Babadook portray the female protagonists who navigate their mental struggles with resilience which challenges stereotypes linking their mental illness with villainy. These depictions also embody the potential to understand the mentally ill in another way: to sympathize with them. This change mirrors the rising of “prestige horror” in the film industry (149); these films juxtapose mental illness with societal issues and call for greater attention to people’s spiritual world. In the films Hereditary and The Babadook, the mothers are portrayed as “three-dimensional” characters, with their mental illness symbolically linked to themes such as religion, family grief, and personal trauma (149). Krone posits that these films also “present mental illness as more of an allegory or symbol through the use of the supernatural” (176). In this way, they complicate the trope of mental illness in horror cinema, rather than solely using it to characterize villains. However, the thematic direction expressed by the creators and the audience’s perception can be vastly different. Krone argues that Hereditary expresses compassion toward mentally ill characters, especially the mother character Annie. However, I see the film as reinforcing a fear of mental illness, particularly through its title, which indicates that mental disorders are inevitably passed down through generations. This implication could further deepen societal fear and misunderstanding of mental illness. Thus, Krone’s interpretation also needs to be supported by further evidence.

Krone is, however, correct when she argues that an often-overlooked issue in horror films that we rarely reflect on is the negative impact of depicting mentally ill characters as villains. Audiences tend to accept these terrifying portrayals as natural. Furthermore, Krone points out that Hollywood rarely casts actors with disabilities in disabled roles. This reiterates the need for more diverse representations in horror films. I believe this book could explore its connection with the Victorian tradition of depicting female madness in literary works, a topic not fully explored in this study. At the same time, this book can also be integrated with queer theory, as this theory similarly challenges the narrative of “normality,” creating intersections with both disability studies and feminist scholarship. Scholars interested in horror cinema, feminist disability studies, and mad studies will likely find this book valuable.

Shiqing Zhang is a PhD candidate at Newcastle University, where she studies children’s literature. In particular, she does research on Ursula K. Le Guin and how her work challenges the conventions of YA literature. She acknowledges the support of the China Scholarship Council (CSC) for funding her research in the UK.