Fiction Reviews

Review of Resurrection: Comics in Post-Soviet Russia

Oskari Rantala

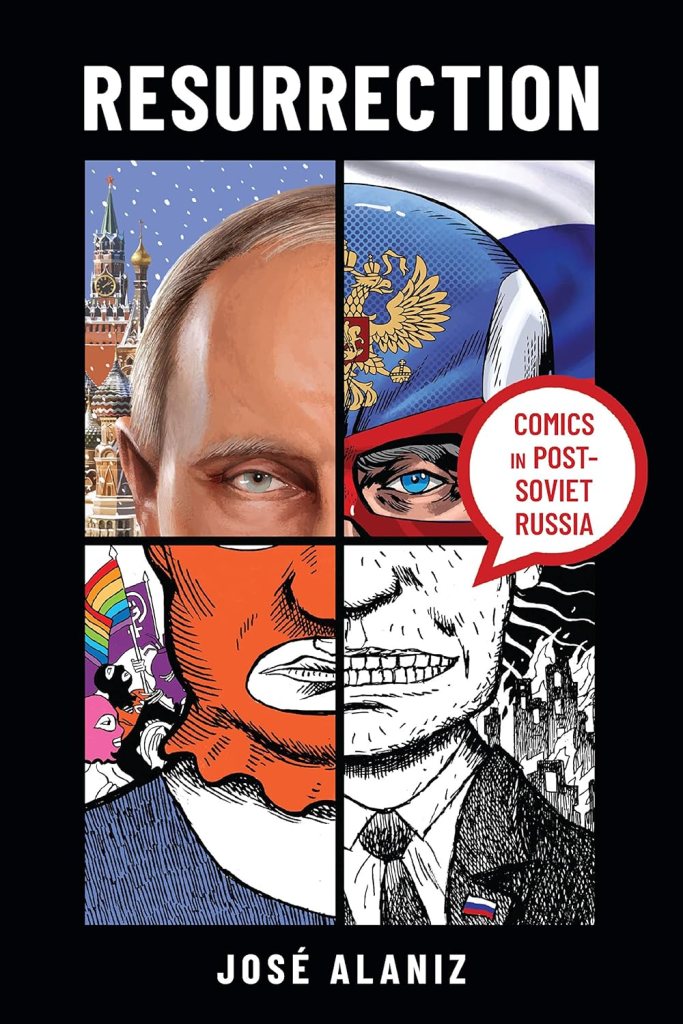

José Alaniz. Resurrection: Comics in Post-Soviet Russia. Ohio State UP, 2022. Studies in Comics and Cartoons. Ebook. 248 pg. $37.95. ISBN: 9780814281925.

.

In his conclusion to Resurrection: Comics in Post-Soviet Russia, José Alaniz cites Alexander Kunin, the director of Moscow’s Center for Comics and Visual Culture. “We live in Russia,” Kunin says. “Here you never know what’s going to happen tomorrow” (210). Indeed, the same month Resurrection came out, a Russian tank column was approaching Ukraine’s capital, and young educated Russians were scrambling to get out of their home country.

The cover image of Resurrection, a collage artwork of the invasion’s architect, became accidentally more poignant than planned. In one of the panels, Putin stares coldy at the reader in front of Kremlin. In another one, he is clad in nationalistic white-blue-red superhero garb complete with the double-headed eagle—the imperial colors and emblems that replaced the communist ones in post-Soviet Russia. Next, we see Putin’s face covered by a colorful balaclava in the style of Pussy Riot and protesters marching with rainbow flags. Since then, demonstrations have been crushed and Russian courts have declared rainbow flags symbols of “an extremist organization”.

Putin is a good choice for the simple reason that he personifies the profound changes which Russia and Russian society have undergone in the past twenty years. Before his reign, there was no viable comics industry in a semi-developed country with close to 150 million literate people. Granted, comics were not a special case in the chaotic 1990s, and Russia lacked quite a few other viable industries as well. A number of interesting and innovative comics were being produced, but publishing them and making a living out of it was a near impossibility. This is where Alaniz’s last book on the subject, Komiks: Comic Art in Russia (2010), ended. With Resurrection, he takes the reader through the three post-Soviet decades of Russian comics.

He takes a closer look especially at Bubble, a company which succeeded in launching a profitable Russian mainstream comics line with a western business model: superpowered action characters sharing the same universe, multi-title crossover events, basing creative decisions on sales figures, and ultimately aiming to develop their properties for film deals. Alaniz offers an intriguing peek at the dynamics of the Russian comics field as he provides room for both the Bubble founder Artyom Gabrelyanov as well as the company’s critics.

Between the camps of art/indie and mainstream/superhero comics, there are some tensions which seem ultimately not very different than what is found in western comics circles, even though the debates might seem more heated in Russia. A similar point could be raised about the infamous Medinsky quote above. Comments along the same lines were common in the first half of the 20th century when comics caused moral panic on both sides of the Atlantic. There seems to be something universal in the ways in which literary cultures adopt visual narratives. For many readers, Russian society might seem quite alien, but on closer inspection the cultural currents are not that unfamiliar.

Resurrection is a scholarly but theory-light book. Most of it is perhaps best categorized as cultural history, but the concluding chapters on masculinity in superhero comics and representations of disability deal more with comics analysis. Both are interesting takes on multifaceted and diverse comics in a culture that is hyper-masculine and dominated by strong and capable men. At the same time, there are disabled comics artist producing innovative works about their own experiences, superhero Putin parodies, and mainstream comics that are almost impossible to distinguish from what is published for the American market.

As far as the cultural history side is concerned, Alaniz at times brings up bits of information that are not something that a foreign layperson would consider very significant: a letter published in a newspapers or something that one of his friends active in the comics scene has told him. As there are over 20,000 newspapers in Russia, what does it actually tell us if one of them publishes a letter holding some kind of a position on comics? My first reaction as a reader is “not very much,” and I would have appreciated a bit more convincing, even though there’s nothing suspect about the main arguments Alaniz puts forward. It is one of the strengths of the book that Alaniz has access to people who have had a major role in the Russian comics scene. In some instances, it is obvious that they are personal friends of the author, and another writer could have discussed their opinions through a more critical lens.

Alaniz places the moment when comics began “to matter” in Russia near the Victory Day celebrations on 2015 when it turned out that some bookstores had removed Maus from their shelves due to the swastika on the cover of Art Spiegelman’s anti-fascist masterpiece. According to Alaniz, comics had “earned the right to be banned” (xvi), even though it was not so much a case of censorship as an outright silly decision by bookstore staff. However, the incident was good for the sales and publicity of Maus—perhaps not what one would expect to happen in an authoritarian country.

Alaniz does not discuss to what extent the emergence of a comics industry and more organized comics fandom is connected to the modern nerd culture in general. Science fiction, urban fantasy, postapocalyptic narratives, and video games seem to be major cultural forces in Russia, judging by the success of authors such as Dmitry Glukhovsky and Sergei Lukyanenko or game franchises S.T.A.L.K.E.R. and Metro 2033 which have expanded into other media as well. Should Russian comics be thought of as a part this wider culture? That is a question that would have interested many speculative fiction scholars.

Oskari Rantala is working on their doctoral thesis in the University of Jyväskylä, Finland, researching medium-specific narrative strategies and medial self-awareness in the comics of Alan Moore. Their research interests include medium-specificity, (inter)mediality, comics and speculative fiction. Currently, Rantala is also the chair of Finfar, The Finnish Society for Science Fiction and Fantasy Research.