Media Reviews

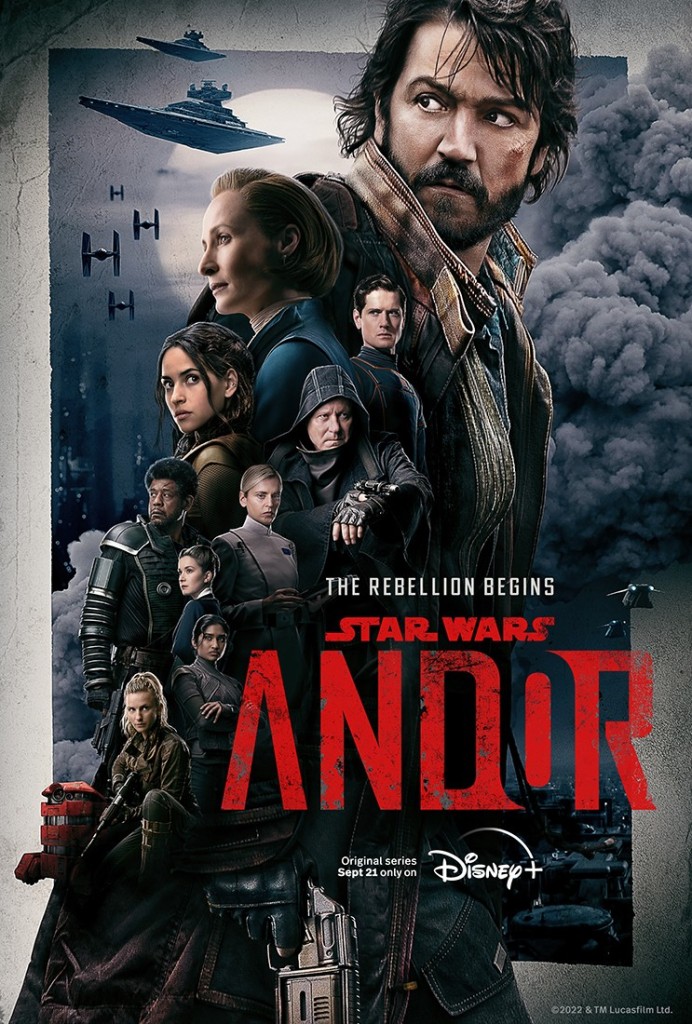

Andor is the fourth Star Wars live-action television series, continuing the development of the franchise following the purchase by Disney. The first season (released so far) takes place across a single year, while the second season is expected to cover a further four years leading up to the events in the film Rogue One. Broadly speaking, the series follows the early stages of the rebellion against the Galactic Empire. In particular, it follows Cassian Andor (Diego Luna) as he becomes a revolutionary, leading up to his death in Rogue One while stealing the plans of the Death Star.

The series ties directly into the later film, meaning the audience already knows the end before the first episode starts. From the very beginning, it is clear that this series is a different kind of Star Wars. In the first episode, we see Cassian shoot two corporate security guards. There is no question, unlike in Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope’s multiple remasterings, of who shot first. From here, the plot first follows Cassian as he tries to sell stolen Imperial technology and then becomes embroiled in a heist and later the rebellion. Second, it follows Syril Karn (Kyle Soller) as he tries to trace Cassian for the murders and then comes into contact with the Imperial Security Bureau (ISB). The first season follows the early stages of the rebellion, the lives of those living under the Empire, as well as those trying to suppress opposition.

Andor takes a notably darker tone than either The Mandalorian (2019-present), Obi-Wan Kenobi (2022), or The Book of Boba Fett (2021-2022). The other three take more of a space-Western setting, covering the outskirts of the galaxy. In Andor, the focus conveys an impression of a franchise less driven by Grogu (“Baby Yoda”) merchandise sales. The closest to product placement we get in Andor is the Kalashnikov-inspired blasters of the rebels.

Andor goes in a much more deliberate political direction. Instead of the usual themes of Star Wars, it is much more about the work of imperialism and the rebellion against it. There are no lightsabers or Jedi superheroes ready to fight the Empire. On both sides of the rebellion, there is a sharp focus on the daily lives of people in Star Wars. As Tony Gilroy explained in an interview: “If you think about it, most of the beings in the galaxy are not aware of Jedi, and have never seen a lightsaber [… ] It’s like, there’s a restaurant and we’re in the kitchen. This is what’s going on underneath the other stuff” (quoted in Hiatt). There are scrap metal workers on Ferrix dismantling ships, prison labour, and the secret work of starting a rebellion—both with the organisation of a heist, as well as the manoeuvring of Mon Mothma (Genevieve O’Reilly) in the Senate.

Similarly, there are no visible Sith Lords seen running the empire. Instead, there is the bureaucracy of the ISB. The staff meetings focus on reports and following orders, not taking initiative. They are also an arena in which ISB supervisors Dedra Meero (Denise Gough) and Blevin (Ben Bailey Smith) go up against each other. They clash over protocols, a power struggle that is more Kafkaesque office politics than a Sith punishing failure with a force grip.

The significance of this is that Andor draws attention to the life and activities of the rank-and-file: those trying to rebel, the ISB and the army against them, and those caught in the middle. Andor has, given the name of the series, the potential to focus on Cassian’s actions. However, Cassian is often not the person leading the action, nor could he (or anyone else for that matter) do it alone. The hero’s journey, even when it involves trying to overthrow a totalitarian government, can often reinforce conservative themes. For example, in films like In Time, Equilibrium, and Dune, there is one special person (and it often is a young man) who leads everyone else to victory.

Andor subverts this hero’s journey. Cassian runs away from Ferrix after being pursued for the killing of two Pre-Mor Security Officers. The Imperial Army establishes a garrison and occupies Ferrix. Early in the season, there is evidence of collective organising in the community, with the banging of pots and pans to warn of the Pre-Mor tactical team. At Maarva (Cassian’s mother)’s (Fiona Shaw) funeral, she posthumously gives a speech via holorecording calling for the people of Ferrix to revolt against the empire. Maarva had been part of an organisation called the Daughters of Ferrix and there is further evidence of organising behind the uprising. Cassian uses this as cover for a rescue, neither inciting nor leading the action.

The first season also later features Cassian being imprisoned on Narkina 5. The representation of prison labour is another departure from the usual Star Wars. Here, the series shifts to a direct portrayal of the Empire’s power. In summary fashion, Cassian is sentenced and shipped off to a penal colony. It is a criticism of the prison-industrial complex, with prisoners making parts for the future Death Star. However, the prison is also part of the Empire’s attempts to maintain order. Knowledge of the prison is kept from the general population, providing a way to both suppress dissidents and information. The prison itself is designed to prevent collective organising, and is overseen with repressive technologies, internal competition, and separation from other prisoners. This is organising against all the odds, with a panopticism that Foucault would have been impressed with. However, inmates find a way to overcome this, with Kino Loy (Andy Serkis) turning from floor manager to worker militant.

The Star Wars franchise has, of course, been concerned with many of these themes before. The original film trilogy reflected on the Vietnam War and Nixon’s presidency. George Lucas modelled the Empire on both the British and American Empires, drawing on Nazi imagery to reinforce the criticism. The story follows the rebellion, albeit focusing on the hero’s journey of Luke Skywalker and other characters. The Prequel films address the rise of fascism and the collapse of democracy. These are more firmly space operas, providing social commentary alongside them. However, subsequent entries in the Star Wars series have not moved this critique much further, other than perhaps the focus on average citizens found in The Clone Wars and Star Wars: Rebels.

This different vision of rebellion and Empire is in part due to Tony Gilroy’s background in spy thrillers as well as his interest in history—and particularly historical revolutions. For example, Gilroy explains the heist subplot was inspired by an account of Stalin’s bank robbery in 1907 (Hiatt). The series often focuses on the dirty work needed for a rebellion. The representation of the rebels themselves is not as clear-cut as in earlier Star Wars. There are political divisions and tensions with a heavy emphasis on the need for sacrifice. There are powerful examples of this throughout including the climax of the prison break with Kino revealing he cannot swim, Luthen Rael (Stellan Skarsgård)’s speech to keep his ISB source in line, as well as Cassian’s future death which looms over the series. This is not a straightforward hero’s journey.

Andor refreshes Star Wars as a social commentary on authoritarianism, empire, and the possibility of rebellion—if not revolutionary change. It is a much more politicised entry into the Star Wars canon, which at the same time centres on the lives of ordinary people. Andor takes Star Wars in a new direction which raises avenues for further academic research on the politics of rebellion, organising, and social change.

WORKS CITED

Hiatt, Brian. “How ‘Andor’ Drew from… Joseph Stalin? Plus: Inside Season 2 of the Revolutionary Star Wars Show.” Rollingstone.com. 10 November 2023.