Media Reviews

Review of I’m Your Man [Ich bin dein Mensch]

T.S. Miller

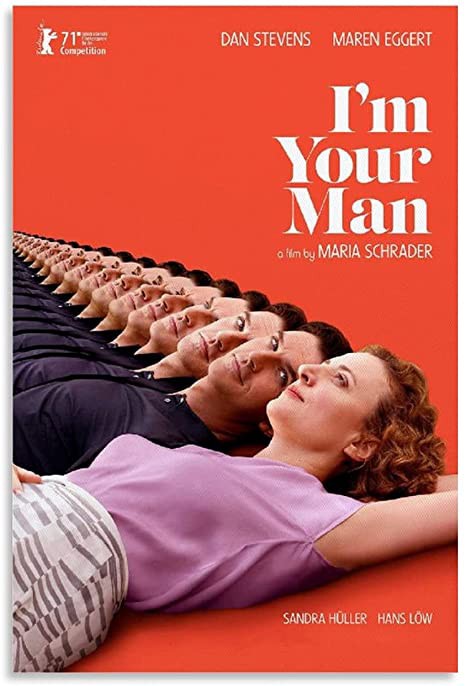

I’m Your Man [Ich bin dein Mensch]. Dir. Maria Schrader. Perf. Maren Eggert and Dan Stevens. Majestic Filmverleih, 2021.

Maria Schrader’s German-language film I’m Your Man [Ich bin dein Mensch]belongs to a by now familiar enough subgenre in science fiction, that of the robot rom-com. Schrader, however, crucially reverses the typical gender dynamics of the genre’s long fembot-filled history. In film, this tradition stretches back at least to Bernard Knowles’s 1949 farce The Perfect Woman and includes more recognizable titles such as John Hughes’s 1985 cult teen sex comedy Weird Science and Spike Jonze’s 2013 film Her, all of which electronically recast the Ovidian myth of Pygmalion and Galatea, the sculptor’s beloved statue come to life. While there is some precedent for this specific premise—the 2014 Disney Channel Original Movie by Paul Hoen called How to Build a Better Boy is one example—I’m Your Man is also notable for the ways it confronts the male gaze undergirding so many stories of eroticized gynoids under the leadership of a woman director, still such a rarity in the world of science fiction film. Students and scholars interested in media representations of artificial intelligence and/or androids will therefore find the film a must-see addition to the ever-widening corpus of such works.

Alma (Maren Eggert) is a recently single academic leading a team working at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin on ancient Sumerian cuneiform tablets as some of the earliest surviving expressions of the human artistic imagination. At the beginning of the film she has already agreed—ostensibly as an exchange of favors with the academic administrator who controls their institution’s purse strings, but possibly for other, more personal motivations as well—to offer her services as an expert evaluator of a new line of romantic companion robots that impeccably imitate a human appearance. Based on a personalized psychographic profile, her own “perfect man” has been created to become an ideal romantic partner. The result is a suave android who introduces himself as Tom (Dan Stevens) and begins showering her with transparently cheesy compliments. “Don’t you like compliments?” he observes with concern, already beginning to adjust his behavior according to her responses. “Do you believe in God?” Alma counters, and, in the way of the old chatbot SmarterChild and many of our contemporary digital assistants, Tom opts for a classically noncommittal deflection: “This is hardly the place to discuss such a question.” Alma thus enters her fixed-length trial period with Tom filled with intense skepticism about the initiative, and her expert report, we are told, will assist policymakers in determining whether such androids will be permitted “to marry, to work, to get passports, human rights, or partial human rights.” The narrative that ensues does indeed hit many of the narrative beats familiar from the romantic comedy, but always with the additional layers of complexity that arise from the science fictional premise. Tom doesn’t simply have to win the more than reluctant Alma’s heart; succeeding or failing at this preprogrammed objective counterintuitively has implications for his very personhood.

In 1950, Alan Turing famously proposed his “imitation game” as a self-consciously imperfect but infinitely more practical replacement for the difficult question “Can machines think?”: could a computer persuade a human subject in a double-blind setup that a fellow human was speaking on the other end of the line? In his own 1995 Pygmalion novel Galatea 2.2, Richard Powers waggishly makes a further substitution, replacing the conventional Turing test with the more specific question of whether a neural net trained on the Great Books could pass the comprehensive exam for a master’s degree in English literature. The roboticists in I’m Your Man have set themselves a no less difficult challenge: it is not the hard problem of consciousness as such that they seek to solve, but instead the hard problem of love, or rather, of romantic and not simply sexual attraction. In the future that the film imagines, fooling the senses is easy, even cheap, with holograms and the androids alike as indistinguishable from humans as Ridley Scott’s replicants. The goal here is much more than a “basic pleasure model,” however, and the kind of uncanny valley that Tom must bridge to reach Alma and win her heart has more to do with the mysteries of human desire, memory, and emotion than any physical stiffness or inhuman jerkiness.

And try to woo Alma Tom does, and try and try. “Failed communication attempts are crucial for calibrating my algorithm to you,” he says good-naturedly upon learning that unsolicited advice about how to improve her driving is perhaps not the optimal way to a woman’s heart: “These mistakes will happen less and less.” Eggert’s performance as Alma communicates an extreme wariness towards Tom at all points and in all ways. After all, not only does she find herself suddenly cohabiting with a strange man, he isn’t even a man, but an unprecedented and unpredictable technological creation: “your thing, your dream partner.” Perhaps more threateningly still, Tom represents a something or someone she might allow herself to fall in love with if she isn’t constantly on her guard. In the first half of the film especially, we see Alma recoil the most viscerally at being told what she likes, that her desires can be solved via algorithm: “You are attracted to men who are slightly foreign,” Tom informs her, explaining his British accent. Such exchanges speak to one of the film’s major thematic concerns, the implications of the algorithms that, visible or not, already run our lives in an increasing number of ways. Along with Alma, we don’t like the idea of being turned into data, or thinking of ourselves as a series of data points in some mainframe to be manipulated and exploited by multinational corporations according to demographic profiles that fit us all too well. Schrader’s film recognizes that the real-world AI revolution of the past decade or so has relied not only on the neural nets and self-teaching algorithms we hear so much about, but fundamentally also on big data as a key component of its formula for success. When Tom locks eyes with Alma, his cerebral processes work on the problem of her heart through access to “mind files from 17 million people.” What’s at stake in falling in love—or not—with a machine seems to have as much to do with our relationship as individuals to new forms of mass computation and abstraction that needn’t achieve self-awareness to have tremendous implications for human life and human lives.

Science fiction stories from the past century and more have given us a number of artificial women manufactured unselfconsciously for a male gaze. This film invites us to consider what might change, in the end, when the genders of the Pygmalion-Galatea relationship are reversed, and when, as in I’m Your Man, the artificial romantic partner is manufactured to fulfill the individualized desires of a particular heterosexual woman. The conclusion of the film may finally be as open-ended as the hard problem of consciousness (or romance), but overall I’m Your Man is certain to provoke much thought and discussion among many different audiences.

T. S. Miller teaches both medieval literature and modern science fiction as Assistant Professor of English at Florida Atlantic University, where he contributes to the department’s MA degree concentration in Science Fiction and Fantasy. Recent graduate course titles include “Theorizing the Fantastic” and “Artificial Intelligence in Literature and Film.” He has published on both later Middle English literature and various contemporary authors of speculative fiction. His current major project explores representations of plants and modes of plant being in literature and culture.