Fiction Reviews

Review of Rose/House

Sarah Nolan-Brueck

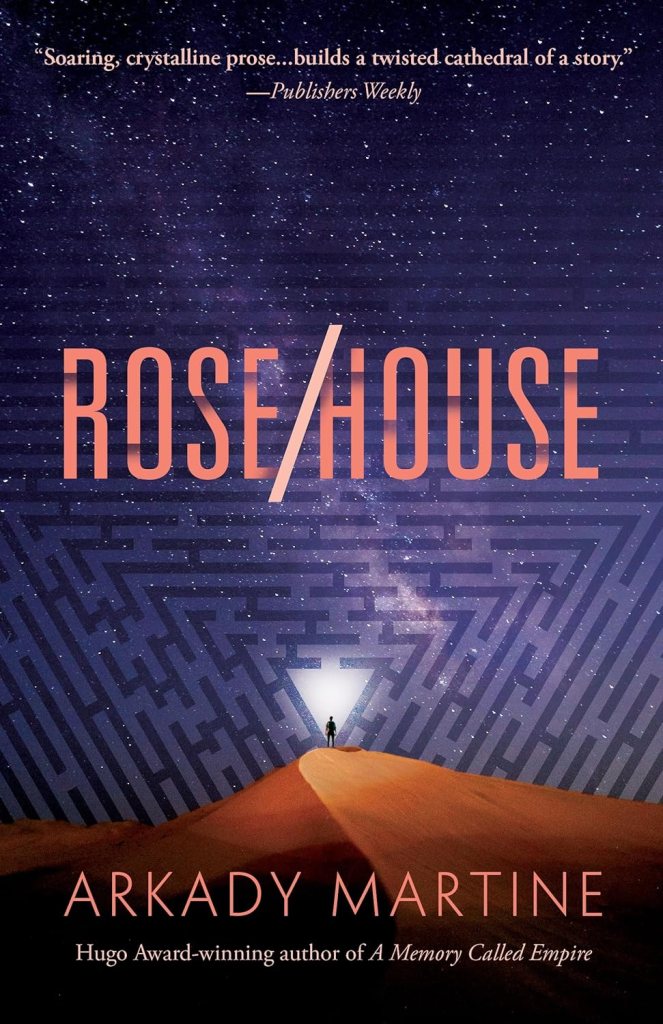

Martine, Arkady. Rose/House. Tor Publishing Group, 2025.

“A person can leave a place without going anywhere at all”—so says Rose House, the sentient home that provides the name and magnetic setting of Arkady Martine’s recent novella (54). At 115 pages, Rose/House is as slim as a stick of dynamite, and nearly as deadly. Where Martine’s Hugo Award-winning Teixcalaan series (2019-2021) takes place in a far-future, sprawling galactic empire, the world of Rose/House is much more intimate—taking place sometime in the next century, in the Mojave Desert community of China Lake. Named for its dried-up body of water, China Lake’s remote, arid setting makes Rose House all the more enchanting—a house blooming out of the desert, full of lush greenery, a swimming pool, and clean energy, a beacon of technological possibility in a region where the most common crime is murdering someone for their water ration credits.

The narrative follows three main characters, Dr. Selene Gisil, Detective Maritza Smith, and Detective Oliver Torres, as they try to solve the ultimate locked-room mystery. Gisil is the protégé of Rose House’s famous architect, Basit Deniau; she is also the only person who is allowed to enter Rose House to access his records, now that he has died. Given this common knowledge, Smith is shocked when Rose House makes a compulsory call to the China Lake precinct to report that there is a dead man on her premises—a dead man other than Deniau, whose body was turned into a diamond and put on display inside the home. Smith calls on Gisil to return to China Lake and help her gain access to the house. To enter, however, Smith must circumvent Rose House’s programming. She must declare herself an entity rather than a person, China Lake precinct rather than Maritza. Despite Torres’s protests and panic, Smith gives up her claim on individual personhood to meet the house on its terms, to be swallowed up by its walls and logic.

Martine’s novella explores architecture as an inspiration for experimentation, digging into the implications of transforming a mundane domestic space into a super-advanced, one-of-a-kind technological display. Rose House is much more than a smart home imbued with sci-fi gadgets and voice command; referred to throughout as a “haunt,” the house itself is sentient. It listens and speaks without any obvious source of audio input or output, and tiny nanobots teem in the space, ostensibly working to keep the house in prime condition. The house normally holds only one dead man, Basit Deniau, who has been turned into a diamond and displayed on a plinth. The border between person and object here is wholly blurred. A house becomes a person; a man becomes a diamond; a woman becomes a precinct.

And yet, there is much we don’t know about Rose House’s origins and history. Beyond one short, ambiguous flash of memory from Dr. Gisil’s point of view, in which she remembers someone diving into a pool, the story takes place entirely in the present moment, after the death of the architect. While the house—the “haunt”—is imbued with a disturbingly omnipresent consciousness, the theme of haunting extends to the power Basit Deniau still holds in death. The memories of his manipulation seep into Gisil’s current reality. Damned to act as his archivist, Gisil’s role as his famous protégé and beneficiary leaves her stranded in her own career, too overshadowed by a dead man to excel on her own merit. Groups of architects, artists, and politicians jockey for a claim on Deniau’s property and legacy, waging ideological and legal battles to access, copy, or repatriate his intellectual and physical property. But Rose House, most of all, is possessed by her departed master. Once the site of lavish parties and admiring guests, Rose House has been emptied and made into a beautiful crypt. Her only job is to guard Deniau’s restructured body and his records from prying eyes—quite literally. As it turns out, Smith is only probing for loopholes because the anonymous dead man did so before her; he attempted to copy Deniau’s retinas, to trick Rose House into handing over her most intimate secret—her source code. In the end, however, our most intimate knowledge of the house comes from the surprising depth of her grief for her creator and for her past life. Though the house is smart enough to see through the imposter’s trick, she allows herself to be taken in, to enjoy the possibility of her beloved’s return, before killing the trickster in an act of vengeful, tragic rage. Rose House is human enough to indulge in delusional nostalgia.

With nods to Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, which also focuses on a home that is “not sane,” as Detective Torres states, Rose/House plays with the borders of what language can impart as both a tool of an artificial intelligence and a way of depicting highly advanced, nearly incomprehensible technology. In this way Martine’s depiction of Rose House—its consciousness and its more indecipherable elements—as well as her flair for odd detail echoes the New Weird-ness of Jeff Vandermeer and the worldbuilding sincerity of Annalee Newitz. If Martine excels in depicting the politics and potentials of Rose House’s intellectual property, a piece we miss out on is the greater illustration of Rose House as a physical space. Though specific rooms are described—the entry hall, the garden room with a glass wall, the vault where Deniau’s designs are stored—, much of the house is depicted only in passing glimpses, as Maritza sprints through the strange space. Nevertheless, Martine’s Rose/House is an impressively rich microcosm of AI’s growing potential and of our responsibility to understand it.

Sarah Nolan-Brueck is a PhD candidate at the University of Southern California, where she studies how science fiction authors critique medical legislation that restricts diverse gendered groups in the United States. Sarah was a 2024 Le Guin Feminist Science Fiction Fellow at the University of Oregon. She has been previously published in ASAP/J, Utopian Studies, Orbit: A Journal of American Literature, Extrapolation, and Huffpost.