Fiction Reviews

Review of Automatic Noodle

Andrea Valeiras Fernández

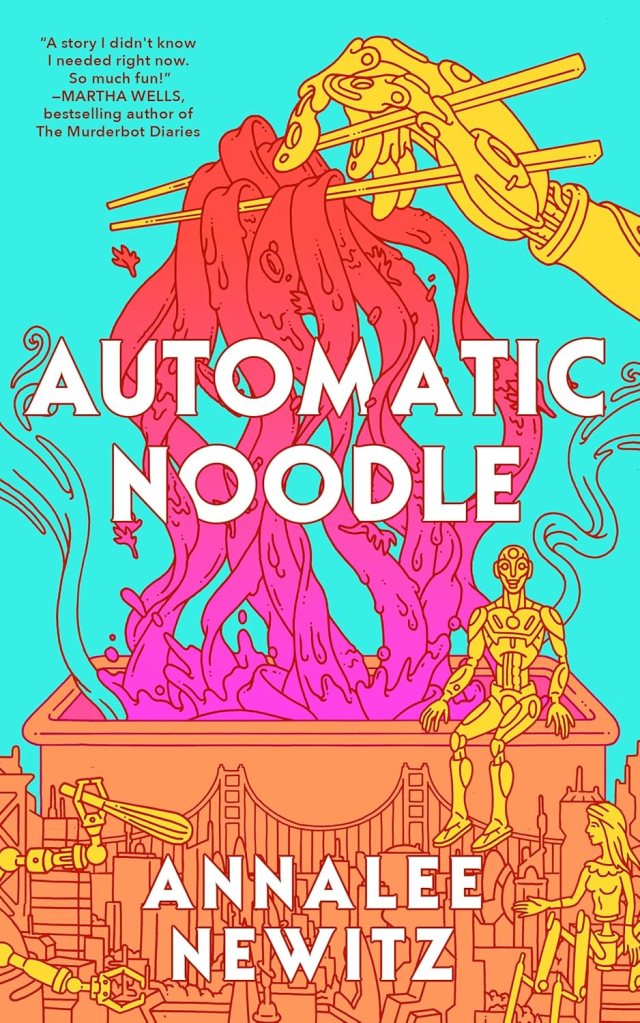

Newitz, Analee. Automatic Noodle Tor, 2025.

This novelette tells the story of a group of service robots—Staybehind, Sweetie, Hands, and Cayenne—with different body shapes, personalities, and backgrounds. They wake up in 2064 after having been abandoned and disconnected for several years during a war (the narrative, therefore, takes place in the not-so-distant future). Their city, San Francisco, is being rebuilt, and no one seems to remember them or the ghost kitchen where they spent years working. However, once electricity flows back through their circuits, the four protagonists know that they must earn money without alerting the authorities or their creditors, and so they decide to reopen the noodle restaurant that the owners had abandoned when the war started. It is not an easy task, though, and they will not be entirely welcome: negative reviews threaten to wipe Automatic Noodle off the map and end the robots’ livelihood.

In the context of speculative fiction, Newitz offers her audience a cozy and hopeful story, building a small world within a larger, significantly more ruthless and broken one after a war. I should mention that, over the last couple of years, several dystopian and utopian novels have presented war and post-war scenarios as a result of the independence of the state of California (for example, Another Life by Sarena Ulibarri). This tells a lot about the sociopolitical climate in which we find ourselves. Furthermore, this novel draws on a series of real and current social problems such as online tension, job insecurity, and the existence of businesses like ghost kitchens. The text reflects the gentrification that pushes people out of their neighborhoods. Another issue is the xenophobia transformed into robotphobia: the protagonists of this story represent their own race (albeit of different models and with very diverse functions), and there are even conditions of belonging that border on slavery. If we were dealing with a fantasy story, they would be elves, orcs, dwarves, witches, or any other creature whose image is marked by prejudice. If the novel were realistic, these robots would actually be people of a different race than the supposedly dominant one. The arguments used against them revolve around their different nature and warn of supposed threats. The most common? “They’ve come to take our jobs.” If we replace “robot” with “immigrants,” we get any of the far-right rhetoric that appears daily on social media and in the news. This story can be classified as “hopepunk”: despite living in a world hostile to them and having to endure segregation, the characters are full of hope and love, to each other and towards the world. They do not only prepare nourishing noodles (selflessly, since they cannot eat them); they try to build a community, a social care system. They are literally a found family.

One of the highlights of this book is the importance of food, which is illustrated in the descriptions Newitz employs: some robots cannot taste or feel the textures, and they complement each other’s scarcities. Communication is also important, since they do not talk as human characters would, so the author creates a “kitchen chatgroup” to give the readers access to their conversations. With the group chat element, we have access to the conversations between the robots, as well as their functions and relationships. This tool gives the reader background information about how the automatic kitchen works and how the robots are interconnected.

However, there is a conflict that cannot be ignored: this book has been published amidst an economic, social, and environmental crisis intrinsically linked to Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI). Advocating for AI rights seems like a bold move nowadays and probably an unfortunate one. There are robots literally taking people’s jobs. Of course, the true root of this problem lies with employers who lay off employees because Gen AI generates profits without demanding fair pay or labor rights. This substitution of human workers such as artists, writers and translators with Gen AI implies that the companies are not only ignoring the labor market bias but also their own image in the public opinion and the environmental consequences that these “robots” (chatbots, image generators, etc.) bring with them. Is this a similar case to those who employ undocumented immigrants because it is cheaper? Of course. But comparing the experiences of robots to real-life immigrants can be problematic at the least. However, Newitz’s novella has layers of sociocultural interpretation that conflict with each other, and it is not surprising that, despite the story’s lighthearted nature, the book may elicit negative opinions as a reaction to the real problem of AI, which Newitz may seem to gloss over. It is, therefore, a kind and emotional story in its plot, but entails a complex subtext that leaves many themes that could be explored in greater depth. However, that is a job reserved for critical readers. The author chose not to offer easy solutions, but instead depicts a small utopic retreat where the main question is: what if we went beyond labels and understood identities?

Andrea Valeiras-Fernández holds a Ph.D. in English Studies. Her thesis concerned the reception of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and its adaptations, analyzing the presence of the text in popular culture. Her academic interests focus on storytelling, worldbuilding (with special attention to costume design), and the social assimilation of different narratives, especially the ones related to fairy tales, including the “Disneyfication” processes. Her publications include articles about the illustrations of the 1920s editions of Alice, the worldbuilding process, and the role of music and poetry in the text. She has also explored Terry Pratchett’s Discworld, studying the importance and meaning of the footnotes as a way for expanding the lore and reinforcing the satirical aspects of the texts.