Media Reviews

Review of Andor, season 2

Giaime Lazzari

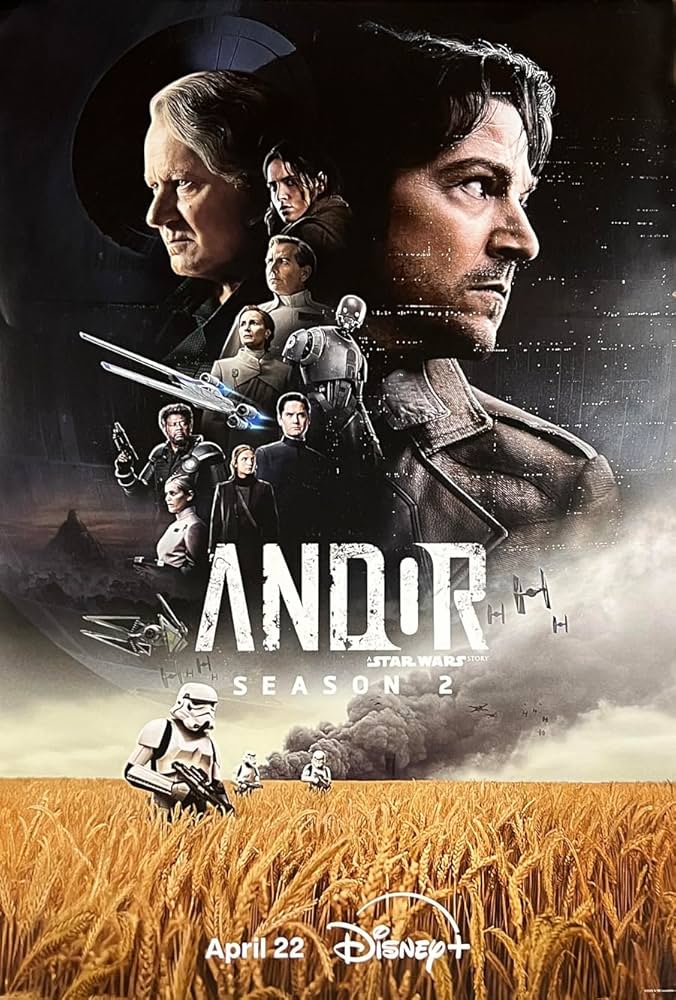

Andor. Dir. Tony Gilroy. Lucasfilm and Disney+, 2025.

The second and final season of Andor confirms the radical ambitions of Tony Gilroy’s project. As Jamie Woodcock anticipated in his review of Season 1 (vol. 53, no. 3), the series covers the five-year span from the Ferrix uprising (S1, E12) leading up to the events of Rogue One. In order to do so, season 2 adopts an unusual temporal structure: twelve episodes arranged into four discrete narrative blocks each set a year apart. The compressed form reflects the show’s curtailed production history: originally conceived as a five-season arc, with each season chronicling one year in Cassian Andor’s life before the events of Rogue One, the project was ultimately reduced to two seasons. The result is a dense, deliberately segmented narrative that forces temporal leaps rather than the slow-burn immersion characteristic of Season 1. But both effect and scope grant several avenues of scholarly interest.

If the first season had already established Andor as the most politically serious entry in the Star Wars franchise, the second pushes further. It stages an even darker account of life under Imperial rule—darker not only in tone but in the domains of violence it is willing to depict. The show represents political violence in its full continuum, including its sexual forms (viewers should be warned particularly about Episode 3, titled “Harvest”). Through the character of Bix Caleen (portrayed by Adria Arjona), it also foregrounds mental health, especially the psychological costs of clandestine life, protracted fear, and revolutionary commitment. One of the season’s most insistent themes is that political resistance always exacts a price: individually, through trauma and loss; collectively, through fragmentation and moral compromise.

Where Star Wars has traditionally handled Imperial oppression metaphorically—allowing audiences to draw analogies to historical or contemporary politics—Andor has seemingly refused this metaphorical distance from Season 1. It dwells on the Empire’s brutality as bureaucratic, economic, and ecological: genocide administered through paperwork; enslavement normalised as labour policy; environmental despoliation rendered systemic. All these aspects are linked by faceless—at times robotised—violence, most evidently depicted in Episode 8, “Who Are You?”.

At the same time, it exposes the relentless pressures on the nascent Rebel Alliance, whether through the grinding search for political legitimacy by Mon Mothma (Genevieve O’Reilly reprising her role) or the perpetual shortage of funds and safe havens. As Variety’s Alison Herman has noted, “without the Jedi—and the binary conception of the Force that comes with them—as major players, Andor is never black-and-white in its morality, even as the show is clear-eyed about the larger issues at play” (2025). This refusal of moral simplification is one of the season’s principal achievements and it is perhaps best embodied by the relationship between Dedra Meero (portrayed by Denise Gough) and Syril Karn (Kyle Soller reprising his role from Season 1).

For scholarly readers, the season opens several avenues of inquiry. Its fusion of political thriller conventions with a rigorously constructed science-fictional environment offers a strong case study in genre hybridisation and in the elasticity of the Star Wars narrative frame. The central character failing their task when faced with systems much larger than them has echoes of the noir genre (see Episode 9, “Welcome to the rebellion”). At the same time, the series is explicit in its treatment of politics: it conceptualises revolutionary praxis, authoritarian governance, institutional violence, and the ethical ambiguities of insurgency with a clarity rarely seen in franchise television. For scholars interested in the politics of the image—and the image of politics—Andor is particularly fertile material. Composition, lighting, architecture, and visual rhythm become tools for articulating forms of control, surveillance, clandestinity, and collective mobilisation; the show’s visuality constructs political meaning rather than merely representing it, marking Season 2 as an especially rich site for work at the intersection of aesthetics, ideology, and media studies. The season also enlarges the material culture of the Star Wars universe, extending down to culinary practices (notably in Episode 3, “Harvest”), domestic environments, and labour ecologies, and demonstrating how detailed production design can anchor a politics of world-building. Finally, with Brandon Roberts taking over scoring duties from Nicholas Britell, the series deepens its sonic register, making Andor a valuable corpus for scholars of music and sound in science fiction.

Season 2 confirms the show as a rare intervention in the Disney era of Star Wars: one that uses franchise infrastructure to stage a rigorous, sometimes disquieting meditation on resistance, domination, and the costs of political agency.

WORKS CITED

Herman, Alison. “Andor Season 2 Review: The Best ‘Star Wars’ TV Series Ends as a Landmark in Prestige Sci-Fi.” Variety, January 2025. https://variety.com/2025/tv/reviews/andor-season-2-review-disney-star-wars-1236372979/.

Giaime Lazzari is a PhD candidate in French Literature at Trinity College Dublin, recipient of the Claude and Vincenette Pichois Research Award (2024-2028). His research focuses on language and space in francophone and anglophone science fictions.