Media Reviews

Review of Superman

Jeremy Brett

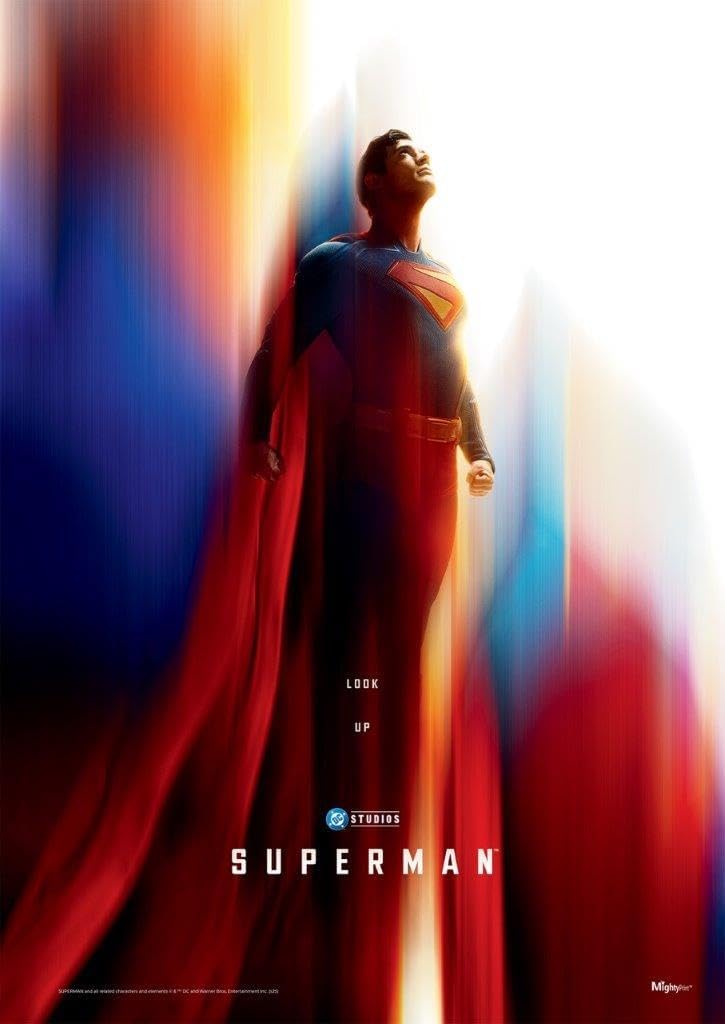

James Gunn, director. Superman, Warner Bros. Pictures, 2025.

The opening shot of James Gunn’s Superman, after an on-screen line of text informs us that “3 MINUTES AGO, Superman lost a battle for the first time”, sees the titular hero (David Corenswet) plummet from the sky and crash headlong into the Arctic ice—beaten, bloodied, and nearly unconscious. He escapes succumbing to his wounds only by being unceremoniously dragged by his cape to the Fortress of Solitude by his rambunctious superpowered dog Krypto. This jarring in media res rupture of the traditional superheroic cinematic narrative (which arcs from origin to early victories to temporary defeat before concluding in a final triumph) signifies a change in focus for the new DC Universe (DCU) away from its predecessor, the Zach Snyder-helmed DC Expanded Universe (DCEU). Whereas the latter was criticized by many for treating Superman as a solemn near-god presenting as a stern Savior-type figure in a dark, desolate world, James Gunn, instead, concentrates much of his efforts on Superman’s inherent vulnerabilities and imperfections.

These facets of Superman’s character tie him to his instinctive and learned human nature and values that he consistently champions. The DCEU characterized Superman as less of an active being and more as a phenomenon, a living incident or event descending from hostile outer space—an outside force that happens to Earth—whereas the Superman of Gunn’s new film is a flawed but striving figure that operates within and as one of the denizens of his adopted planet. That conflict over definitions is the central debate at the heart of Superman—what does this superbeing imbued with immense power to destroy or to preserve, represent to the people living in his shadow? Certainly Superman is not the first product of superhero media to analyze the relationship of the hero to the world around them, but few connect the hero’s nature to his fallibility, the possibility of his losing or failing, as explicitly as the film does.

Superman is frequently overmatched in the film, facing savage attacks at the hands of the “Hammer of Boravia,” the armored metahuman sent to attack Metropolis; by “Ultraman,” the mysterious villain serving as the muscle behind Lex Luthor (Nicholas Hoult)’s brain; by Luthor’s other powered warrior “The Engineer” (Maria Gabriela de Faria); and by the morally compromised Kryptonite-wielding Rex Mason/Metamorpho (Anthony Carrigan). The film embraces the immediacy and brutality of violence, but less, perhaps for mere spectacle and more to signify Kal-El’s own embrace of the human condition. The fighting and failing and getting up and trying again is a function of being mortal, a process in which Kal willingly engages and considers a fundamental component of his own nature. In a climactic exchange with Luthor—a man fundamentally defined by his opposition to Superman as a deadly and otherworldly threat to the planet, who has just referred to Superman as “you piece of shit alien!”—Kal fervently declares,

I’m as human as anyone! I love, I get scared. I wake up every morning, and despite not knowing what to do, I put one foot in front of the other, and I try to make the best choices that I can. I screw up all the time. But that is being human, and that’s my greatest strength. And someday, I hope, for the sake of the world, you understand that it’s yours too.

Kal is an active entity of constructed choices, the most significant of these being his willingness to embrace the importance and sanctity of life everywhere. Bedrock compassion for the least of humanity is not new to the image of Superman—we’ve seen it touchingly deployed in such comic book instances as Grant Morrison’s 2005-2008 All-Star Superman series—but Gunn’s film centers it as the core of his heroic identity more than any other example in live-action Superman cinema. That aspect of Superman’s heroism has been much better served in animation—both Superman: The Animated Series (1996-2000) and My Adventures with Superman (2023-present) understand it well.

That choice to serve life defines Superman. During a battle with a kaiju in downtown Metropolis sent by Luthor as a distraction, Kal not only rescues people from imminent death, but rushes a squirrel out of harm’s way and, while nearly being crushed underfoot, gently shoos a wandering dog away from the area. His double-pronged strategy to save the lives of both people and the monster itself is a direct contrast to the actions of the corporate-sponsored superheroic Justice Gang: Guy Gardner/Green Lantern (Nathan Fillion), Hawkgirl (Isabela Merced), and Mister Terrific (Edi Gathegi), who kill the creature without compunction over Kal’s frustrated objections. Later on in the film, following Krypto’s abduction by Luthor’s forces, Kal turns himself in to the authorities in hopes of being taken wherever Krypto is being held. When Lois Lane (Rachel Brosnahan) says, “It’s just a dog”, Kal responds in the most compassionately human way possible: “I know, and he’s not even a very good one. But he’s alone, and probably scared.” Notably, Superman’s first in person confrontation with Luthor has him smashing into the latter’s office, enraged, demanding, “Where’s the dog?”

Kal’s concern for the smallfolk of the world gives him added ethical dimensionality lacking in the Justice Gang or in, say, his darker DCEU counterpart. That added complexity, ironically enough, derives from Kal’s simple core belief in the inherent goodness of people, and gives both his character and the film an emotional brightness lacking in much superhero media. When Kal protests to Lois at one point that he is, in fact, “punk rock”, an amused Lois laughingly denies this, and then says, “My point is, I question everything and everyone. You trust everyone and think everyone you’ve ever met is, like… beautiful.” Kal responds, “Maybe that’s the real punk rock.” At bottom, Superman is a hero whose mightiest powers are the implementation of radical kindness and his unshakable belief in its efficacy. If we accept that superheroes are symbolic instruments for the ethics we want to see valued in the world, presenting the most powerful being on Earth—a man with godlike abilities—as dedicated to the idea that everyone has worth and deserves compassion, is a beautifully revolutionary statement.

And there is great emotional resonance in Kal’s desire to live his values in the face of real-world political complexities, impractical as that choice might be. A powerful moment in the film comes when Lois conducts a mock interview with Superman concerning his recent intervention in an international conflict, noting his illegal entry into a sovereign country on his own, without the approval of or even consulting with US authorities, and de facto acting as a representative of the United States on foreign soil. A frustrated Superman can only exclaim, “I wasn’t representing anyone except for me! And, and, and… doing good… People were going to die!”The exchange cuts to the heart of the contradiction inherent to the image of the superhero as they operate in the world—what responsibilities do superpowered beings owe to human-established systems of law and sovereignty? And do those systems take priority over the preservation of life? These kinds of questions have relevance in the real world, where around the world we see increasing interest in extra-governmental and communal ways of living that value life over commerce, justice over laws, and the dignity of peoples over profit.

Kal’s worldview, one in which each life is deemed of value, is diametrically opposed to Luthor, a rat’s nest of ego and envy enmeshed in a system of hypocritical objectification. Objectification, because Luthor—like any number of real-world politicians and CEOs—regards his fellow humans as tools to be used in the furtherance of his own ambitions. He claims to be acting in the name of humanity, yet his machinations produce catastrophic levels of death and destruction. His obsession with subduing the “threat” of Superman leads him to ruthlessly shoot an innocent man in the head right in front of the captive hero. Luthor maintains a private prison within a pocket universe, in which he has jailed not only criminals but his personal enemies (including ex-girlfriends) and political prisoners that various governments want hidden away beyond the reach of the media and accountability. His master plan involves manipulating the nation of Boravia into invading and occupying the neighboring country of Jarhanpur—risking untold casualties—all to maneuver Superman into his control. Luthor views Superman in the DCEU model, as an alien thing who only inspires fear and (for Luthor, a much greater sin) feelings of weakness and inferiority. At one point he rants,

I can’t stand the metahumans, but he’s so much worse. Super… ‘man.’ He’s not a man. He’s an it. A thing with a cocky grin and a stupid outfit, that’s somehow become the focal point of the entire world’s conversation. Nothing’s felt right since he showed up.

Luthor is a supervillain, at base, because he conflates his own superiority with that of humanity, sublimating the latter into the former, whereas Kal is a hero because he chooses to sublimate his alien self into embracing humanity and making weakness its own strength.

The film is ultimately grounded on the power of choice. Kal became Superman in large part because he was inspired by the legacy of his birth parents on Krypton. Partway through the film, however, Kal faces an existential crisis in learning from a recording by his birth parents that he was sent to Earth not to serve humanity but to rule it and preserve his Kryptonian heritage by taking multiple human wives and spreading his genetic code. This revelation turns much of the planet against Kal—assisted by Luthor’s manipulation of social media to target him—but the doubts raised in Kal himself do even more damage. Devastated that his drive to do good sprang from a lie, Kal renews his confidence in his mission after a conversation with his adoptive father Jonathan Kent (Pruitt Taylor Vance), who reminds Kal that his choices and his actions are what define him, not the choices made for him. What Kal wanted the message from his parents to mean, says more about his character and his goodness than the message itself. Heroism is a conscious decision, the film argues, and Kal’s embrace of radical kindness represents the choice that each of us need to make as we move through the unequal and unjust world around us. In this, Superman reinforces the multidimensional nature of the superhero image and its function as a reflection of the values that we cherish most in ourselves and with each other.

Jeremy Brett is an archivist and librarian at Cushing Memorial Library & Archives, Texas A&M University. There he serves as Curator of the Science Fiction & Fantasy Research Collection, one of the largest of its kind in the world. Both his M.A. (History) and his M.L.S. (Library Science) were obtained at the University of Maryland, College Park. His professional interests include science fiction, fan studies, and the intersection of libraries and social justice.