Fiction Reviews

“When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, ‘Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.’ To this day, especially in times of ‘disaster,’ I remember my mother’s words, and I am always comforted by realizing that there are still so many helpers — so many caring people in this world.” – Fred Rogers

These words, from a 1999 interview, were famously posted in a viral Facebook post by PBS in response to the horrific Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting on December 14, 2012, and to this day are frequently resurrected after countless other senseless tragedies. Apocalyptic SF is replete with examples of the worst of humanity coming to the fore in the face of adversity and catastrophe. Another well-worn trope in such works is the helpless damsel in distress, doomed to sell her soul, or her flesh, in a desperate attempt to survive. More often than not, she is the victim of physical and/or sexual assault. Lastly, teamwork by male and female protagonists inevitably ends in comfort sex, a one-night stand (or sudden sequence of such events), often to be regretted in the morning or soon pushed out of the narrative as unimportant, fading into the background as if it were just one more trite plot device to be ticked off the author’s standardized to-do list. To Risse’s credit, her debut novel, Inland, only features the last of these three over-used tropes. Risse’s novel quietly celebrates Mr. Rogers’ “helpers,” although it takes some of her characters considerable time and effort to come to the same realization.

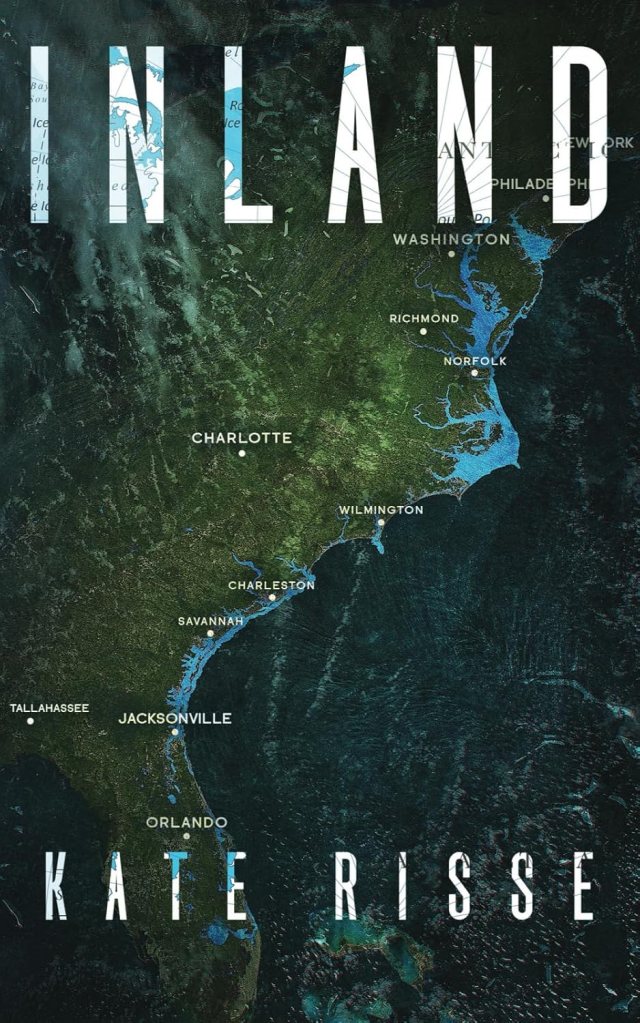

The tale begins soon after the beginning of a vaguely described weather catastrophe that, without warning, floods the eastern seaboard of the US. Speculations by Martin (who, it is insinuated, has some scientific background in climate change) sprinkled throughout the novel suggest it is related to years of rising sea levels and the mass thawing of glaciers and Antarctic ice, coupled with sudden shifts in the ocean currents (think The Day After Tomorrow with Noachian rain and waves rather than flash-freezing Arctic superstorms).

In contrast to many fictional cli-fi catastrophes, Risse’s is set just around the corner, in 2026, the author explaining that she wanted to portray climate change as “unwinding faster than was initially thought, or at least communicated to the public…. I decidedly didn’t want my novel to be a dystopian story set in the far-flung future. I wanted it to be about where we might possibly be heading soon and how that’s not a good direction” (Semel).

Boston native Kate Risse is intimately familiar with the Florida Panhandle coastline and barrier island where the novel begins, having spent many summers vacationing there. In interviews she credits the destruction she witnessed in the aftermath of Hurricane Michael in 2018 as a major motivation behind the novel (Rowland; Semel). In addition to her lived experience along the eastern seaboard, Risse also draws upon her Ph.D. in Hispanic Studies (Boston College) and her climate justice and Spanish language/culture courses at Tufts University in crafting details for her story (“About”).

This cli-fi ecocatastrophe is written in first person, the unfolding disaster described through the eyes of Juliet and the younger of her two sons, sixteen-year-old Billy. Individual chapters focus on Juliet’s desperate attempt to get home to Boston from her mother’s Dog Island beach home on the Florida panhandle and Billy’s equally desperate attempt to survive as the ocean swallows his Boston neighborhood and unexpectedly leaves him to fend for himself. The story of a second family, who lives a few blocks away, comprised of Martin (in Florida for a business deal) and his two teenage daughters, schoolmates of Billy (also stranded without adult supervision in the wake of the disaster), is intertwined (figuratively and literally) in the narrative.

A MacGuffin of a complete disruption of all communication systems cuts off the parents from their stranded children, significantly raising the tension and driving Juliet and Martin’s desperate road trip north—or, rather, north-ish—following an inland path that allows them to not only play the role of good Samaritan, but be the repeated beneficiaries of similar grace. This is fortunate for the characters, as there is an apparent complete lack of governmental aid above some very limited local help within selected communities. While Juliet is openly skeptical of the basic goodness of humanity and repeatedly expects the worse from others, she is more often than not surprised to find that there are, indeed, as Fred Rogers offered, plenty of “helpers,” even in the worst of situations. This is not to say that Risse’s story is a Pollyanna tale; her characters also encounter realistic brutality and harrowing situations. But through these challenges they also discover their inner strength and hone their resiliency, all while learning to let go of parts of their old lives that no longer seem important while simultaneously holding fast to what truly matters.

The widespread failure of most radio, television, flip phones, and internet communication is exacerbated in the novel by a government smartphone ban that had gone into effect some months before. This ban was not intended to save the country’s youth from the mind-rotting effects of social media per se, but literally to prevent their brains (and bodies in general) from being poisoned by “toxic metals and radiation” supposedly associated with the phones (152). Again, the specifics behind the ban are doled out sparingly in the novel, alongside conspiracy theories and banal parroting of the government’s official pronouncements of the dangers. Fortunately, Billy and Juliet have contraband smart phones, and manage to send a few precious texts to each other, enough to convince Martin and Juliet that their children are still alive and attempting to leave Boston together.

While the first part of the parents’ road trip is told in great detail (from Dog Island, Florida, through West Virginia), the rest is either apparently uneventful (which seems strange given the trials the characters endure before this time) or held back for some other reason, until their arrival in southern Vermont. The novel ends with more questions than answers (not the least of which being an unshakable feeling that there is more to Martin than he is letting on), but does give the reader some closure in the form of the main characters’ emotional and physical status. There is certainly room for a sequel, which Risse has considered writing (Semel).

Taken in total, the work did not strike me as necessarily suitable for intense scholarly analysis. However, it would be interesting to see how different aged audiences might read the cellphone subplot in particular, especially given that the story is told from the viewpoints of individuals from two generations. I could see this book being used in a Climate Change Literature or Science and Society class at the college level; it could lead to some quite interesting class discussions and student personal reflections.

WORKS CITED

“About.” KateRisse, accessed 27 Sept. 2025, https://www.katerisse.com/about.

“Mr. Rogers Post Goes Viral.” PBS News, 18 Dec. 2012, www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/fred-rogers-post-goes-viral.

Rowland, Kate. “Creativity Never Ends: Kate Risse on Writing ‘Inland’ and Thinking About the Future of Our Planet.” The Justice, 22 Oct. 2024, www.thejustice.org/article/2024/10/creativity-never-ends-kate-risse-on-writing-inland-and-thinking-about-the-future-of-our-planet

Semel, Paul. “Exclusive Interview: ‘Inland’ Author Kate Risse.” PaulSemel, 1 Aug. 2024, paulsemel.com/exclusive-interview-inland-author-kate-risse/.

Kristine Larsen, Ph.D., has been an astronomy professor at Central Connecticut State University since 1989. Her teaching and research focus on the intersections between science and society, including Gender and Science; the links between pseudoscience, misconceptions, and science illiteracy; science and popular culture (especially science in the works of J.R.R. Tolkien); and the history of science. She is the author of Stephen Hawking: A Biography, Cosmology 101, The Women Who Popularized Geology in the 19th Century, Particle Panic!, Science, Technology and Magic in The Witcher: A Medievalist Spin on Modern Monsters, and The Sun We Share: Our Star in Popular Media and Science.