Fiction Reviews

Review of The Blaft Book of Anti-Caste SF

Paromita Sarkar

Samuel, R.T., Rakesh Khanna, and Rashmi Ruth Devadasan, editors. The Blaft Book of Anti‑Caste SF. Blaft Publications, 2024.

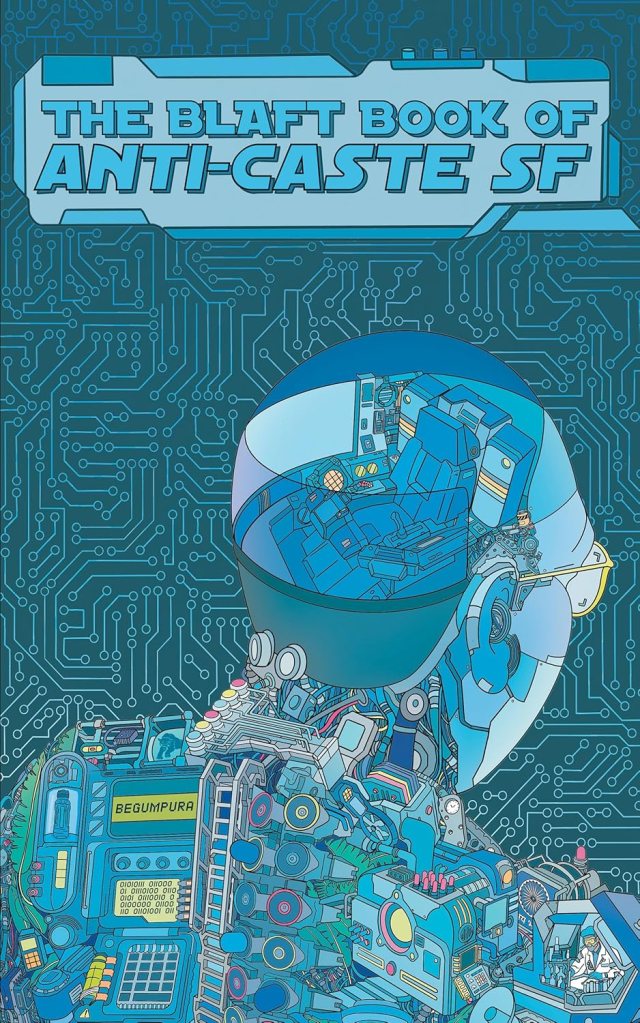

The big blue stature of The Blaft Book of Anti-Caste SF (2024), lined up on any shelf, cannot go unnoticed. The moment you pick it up, Priyanka Paul’s beautifully illustrated Mecha Ambedkar—set against a background of circuit networks—greets you, carrying the iconographies of the Indian anti-caste movement on its back, moving toward Begumpura, the utopian casteless city envisioned by Saint Ravidas. In the next few seconds, as you flip through the pages for a quick glance, you’re likely to stop and look—either because of the comics strewn in between, the unexpected mix of established and emerging writers, or simply because the story titles are so compelling. If not the playful ‘Meen Matters’, then the solemn and arresting ‘In the Extreme Silence of Agrahara’ is bound to intrigue you.

The 428-page anthology, edited by R.T. Samuel, Rakesh Khanna, and Rashmi Ruth Devadasan, and published by Blaft Publications, is a riot. It stares back at you. It jolts you. It urges you to read it. The unabashed attention the book’s visual aesthetics demand is matched by a form and content that refuse to be “structured” or “formal” in any traditional sense. Disrupting the standard idea of an anthology, this collection seeks to expand beyond the textual, including works that interrupt any illusion of narrative unity—graphic stories, a speculative magazine, and stories that refuse closure. The visual and the textual intersect through audacious ideas, opening up a new form of anti-caste thought and resistance. This form does not rely on a retrospective historicization of Dalit movements, nor is it a speculative veneer imposed artificially upon them.

The violence of caste is crucial in understanding the radical potential of the anthology. The caste system, a form of systemic violence and social stratification, has long afflicted South Asian societies, such as India. These social stratifications, historically codified in ancient texts like the Manusmriti or The Laws of Manu, have been used as methods of marginalizing and humiliating various Indigenous and caste communities under the umbrella term ‘Dalits’ or the Broken—a term used by Jyotirao Phule, a historical anti-caste writer and activist from Maharashtra, India. The term has historically been contested. Kanshi Ram, for instance, referred to such communities as ‘Bahujans’, the Marathi word for majority (Chandra 148).

Akin to experiences of African American communities in the United States, both caste in India and race in the US have been prevalent sites of comparative scholarship, building an ‘afro-dalit’ scholarship (Prashad), present in interactions of anti-race activists like W.E.B. DuBois and anti-caste activists like B.R. Ambedkar. These experiences have been vocalized and politicized often in fiction and autobiography. The civil rights and anti-racism group Black Panthers from the U.S., in fact, was a key inspiration in the formation of Dalit Panthers, an anti-caste organization founded by JV Pawar and Namdeo Dhasal, in the 1970s (Satyanarayana and Tharu 61). Writings from or about such communities have relied on an ‘authentic’ aesthetic, as Sharankumar Limbale, another prominent Dalit writer and activist, suggests. Many of these works have utilized realism or the autobiography as a mode. For those interested, a powerful and prominent example is Joothan (1997) by Om Prakash Valmiki as well as the anthology of Marathi Dalit voices, Poisoned Bread (1992) edited by Arjun Dangle. The Blaft Book continues vocalizing such experiences of caste and of pitting oneself against the system of caste. The anthology moves away from an apparent ‘authentic’ and ‘realistic’ mode to an exploratory one, like speculation or science fiction—similar to the practices of Afrofuturism (continuing political solidarities across cultural movements) and the works of Samuel R. Delany, Octavia Butler and Nnedi Okorafor that reconfigured Black histories and futures. Recent scholarship on other marginalized futurisms such as Chattopadhyay’s “Manifesto” suggests a rising pattern of works and movements that vocalize marginalized experiences while reorienting the SF form: a new form of possibilities and ‘playfulness’ emerges where SF and its tropes too become suspect (17). The anthology’s publication adds another dimension to the scholarship on Futurism. It tackles the problem of introducing these historical and political experiences into the speculative mode and vice versa, bringing forth a collection that is expansive in frame.

As an experimental and pioneering anthology, the mix of writers is particularly interesting, with about thirty-two writers across boundaries of space, time, and languages. The inclusion of writers like Bama, Gogu Shyamala, Gouri, and P.A. Uthaman gestures toward an already extant speculative imaginary within works of Dalit and anti-caste writers, though they are rarely read as SF writers in India, which (popularly) remains shaped by a Hollywood-inflected Sci-Fi temperament. Through this anthology, Blaft reorients how we read these writers, even as it expands the contours of the genre itself. Speculative fiction here becomes porous, leaking across literary categories, voices, languages, and temporalities. The very form of the anthology resists any settled or stable identity. Jumping across writers—past, present, and emerging—the book traces the evolving possibilities of writing anti-caste thought into the speculative, the fantastical, and the futuristic.

This porosity is not just temporal but spatial. The collection moves across terrains: from Dalit subjectivities in the rural settings of Bama’s “Korali” or Gogu Shyamala’s “The Phantom Ladder” to the urban nightmares and dystopias of Gouri’s “The Demon That Sits On Your Chest” or Yukti Narang’s “Kitchen Glob”; from the spectral silence of an afterlife Agrahara by Aswathy K. Raj to the nightmarish vision in Snehashish Das’ “Death of a Giant in a Godless Country” or Gautam Vegda’s short story series from ‘Supernova’ to “Vultures on Mars”; from the digital and outer spaces of comics like Yeswanth Mocharla’s “Looly Cooly”—featuring a delivery-boy with “monster-anger”—to Bakarmax’s (alias Sumit Kumar) “Spacewali,” about a “kaamwali” in India’s space lab and to Kunal Lokhande’s provocative take on a gaming channel turned religious sect in ‘Sanatan Gaming’. Even when it comes to stringing together an SF adventure, the anthology does not disappoint; the Birthday Gurlz in “Meen Matters” by Rashmi Ruth Devadasan remain memorable in a post-apocalyptic zombie-filled Chennai.

In all these stories, caste is constantly altered and ridiculed to expose its structures. These distinct spaces do not function as sites of just cognitive estrangement, as they might in traditional SF. Rather, they are loud, grounded anti-caste assertions that echo beyond the present—to ridicule, mourn, rage against it. It is bleak, yes, but it is also powerful: a declaration that caste does not dissolve even in outer space, or in death, or in data. Instead, its haunting continues.

The peculiar thing about caste in today’s digital India is this: to envision a caste-free space, one must first speak of caste. Yet, to speak of it is often seen as propagandist, anti-meritocratic, or non-factual—unless, of course, it comes in the form of a popular casteist slur, an endogamous matrimonial startup, or an innocuous display of caste pride masked as ancestral heritage. Over the past decade, caste has steadily permeated the digital space—through both subtle gestures and overtly violent threats. In parallel, affirmative caste conversations and movements have continued reclaiming these spaces, resisting the overwhelming presence of digital Brahmanism with counter-assertions, memorialization, and imaginative world-building. Artist-activists have become ever more present—and ever more vulnerable—but they persist, intervening nevertheless.

The rise of Dalit and Bahujan creators within these popular digital and speculative spaces points toward new futures for the anti-caste movement. It is into these popular terrains that The Blaft Book of Anti-Caste SF enters—not merely as a literary or political intervention, but as a disruptive method of imagining caste itself. At one of the book’s launches, Rahee Punyashloka, one of the authors, used the term, “audacity” when talking about the anthology. Later that evening, of all the things I remembered when reading the recently bought anthology, the term “audacity” stuck around. To play “audaciously” in these spaces is not just stylistic—it is tactical. This anthology is not just an intervention into the publishing sphere of Indian science fiction; it is a conceptual reorientation of how caste is written, imagined, and published. It shifts from the realist or life-writing modes traditionally associated with Dalit literature, toward a poetics of speculation, friction, and rupture. Here, the anthology hits its mark most forcefully.

The comics embedded within the prose narratives do not simply supplement the written word—they interrupt it. They disrupt the expectations of the reader, and in doing so, make visible an imaginary of anti-caste possibilities that refuses to conform. The fictional magazine insert—“Margin Mag” by Sudarshan Devadoss and MK Abhilash—and Punyashloka’s piece further challenge the anthology’s unity, by functioning as a meta-text that speaks both within and beyond the volume. “Margin Mag” imagines a future in which Dalit history is publicly commemorated with hopeful anti-caste/anti-discrimination WhatsApp updates and ads for anti-bias devices like “FairEar”, while Punyashloka in “The R.V Society for Promotion of Underground Sci-Fi Writings” talks about encountering the anthology’s call for stories and journals the intimate, messy process of writing anti-caste speculative fiction itself. These disruptions are not digressions; they are structurally integral to the work’s method of expression.

Blaft Publications is one of the few independent publishers in India committed to bringing regional pulp and popular fiction into the literary mainstream. In the past, titles like The Blaft Anthology of Tamil Pulp Fiction and Ghosts, Monsters and Demons of India have foregrounded the mythic, the folkloric, and the marginal in English translation—reclaiming stories that have long existed outside elite literary circles. Their latest anthology of anti-caste speculative fiction, a community project clearly put together with care, extends this legacy with quiet precision. The anthology does not seek to offer narrative closure or stable resolutions. It resists unity, embraces disorder, and insists on the porousness of genre, of time, and of caste itself. Its stories speak from and across differences of borders, languages, and spaces—from the ghostly rural, to the fragmented urban, to digital futures, and imagined post-caste presents often encountering, embracing or enduring science and technology. It opens up not only what caste has been but what caste could mean in speculative registers—how it might linger, mutate, or be abolished in these worlds we have not yet built. The promise remains, though only partly fulfilled. Blaft’s new anthology is a groundbreaking chapter in South Asian SF and anti-caste literature; the full potential of the endeavor awaits to be realized, hopefully further opening up dialogues between anti-caste thought and speculative fiction across contexts and borders.

WORKS CITED

Ambedkar, B. R. Letter to W.E.B. Du Bois. Circa 1946. W.E.B. Du Bois Library, University of Massachusetts Amherst. South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA), digitized by Gary Tartakov, https://www.saada.org/item/20140415-3544.

Chandra, Kanchan. Why Ethnic Parties Succeed: Patronage and Ethnic Head Counts in India. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Chattopadhyay, Bodhisattva. “Manifestos of Futurisms.” Foundation: The International Review of Science Fiction, vol. 50, no. 2, 2021, pp. 8–23.

Du Bois, W.E.B. Letter to B.R. Ambedkar. 31 July 1946. W.E.B. Du Bois Library, University of Massachusetts Amherst. South Asian American Digital Archive, digitized by Gary Tartakov, https://www.saada.org/item/20140415-3545.

Prashad, Vijay. “Afro-Dalits of the Earth, Unite!” African Studies Review, vol. 43, no. 1, 2000, pp. 189–201. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/524727. Accessed 9 June 2025.

Satyanarayana, K., and Susie J. Tharu, editors. The Exercise of Freedom: An Introduction to Dalit Writing. Navayana Publishers, 2013.

Paromita Sarkar (she/her) is a writer and a researcher based at Jawaharlal Nehru University in India. She explores the intersections of speculative fiction, anti-caste thought, and media in India. Her areas of interest include Science Fiction, Marginality Studies, Futurism, Cinema Studies, and Popular Culture. She has presented her research on Afrofuturism, marginality, science fiction, and popular culture, at national and international conferences