Media Reviews

Review of Daredevil: Born Again

Jeremy Brett

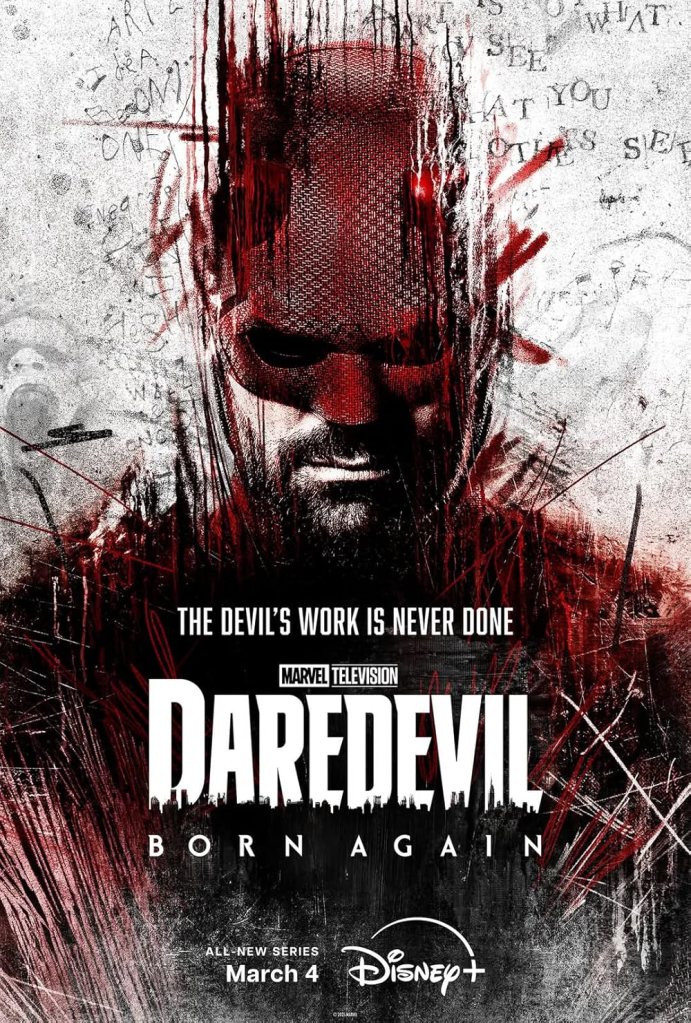

Scardapane, Dario, Corman, Matt, and Ord, Chris, creators. Daredevil: Born Again, Season 1. Marvel Studios, 2025.

The themes of Marvel’s restarted gritty superhero show Daredevil are made manifest (indeed, quite unsubtle) in the opening credits, which depict (to the strains of contemplative theme music that quickly grow pensive) the crumbling away of the old—images of Daredevil’s iconic horned helmet, Daredevil’s criminal archenemy Wilson Fisk/Kingpin (Vincent D’Onofrio), Lady Justice, the steeple of Matt Murdock’s beloved church, a sign for ‘Nelson Murdock Page, Attorneys at Law’, the Statue of Liberty—only for the fragments to reassemble into a reborn Matt /Daredevil (Charlie Cox). What was, now passes away as both Murdock and Fisk look to reidentify themselves both within and beyond traditional systems of governance and control.

But the central theme of the show is not merely resurrection, but instead a revolving and returnto the same point of existential origin as multiple characters attempt to remodel themselves but find, in doing so, that efforts at personal transformation often expose the adamantine and unchanging core of one’s character, motivations, desires, and vulnerabilities. For both Murdock and Fisk, a jarring act of personal violence inspires a personal reexamination of themselves and the worlds in which they have traditionally moved. In Fisk’s case, it is his having been betrayed and shot in the face by his protégé/ward at the conclusion of Marvel’s Echo (2024) —that trauma caused him to temporarily abandon his criminal career and his beloved wife Vanessa (Ayelet Zurer), rethink his life’s priorities, and inspire an ultimately warped and misguided need to “serve the city”. For Matt, this process begins in the opening minutes of the show, where his best friend and law partner Foggy Nelson (Elden Henson) is gunned down in front of their mutual friend Karen Page (Deborah Ann Woll) by Matt’s old adversary Benjamin Poindexter/Bullseye (Wilson Bethel). An enraged Matt, clad as Daredevil, violates the traditional superhero code of restraint by deliberately tossing Bullseye off a roof and nearly killing him. It is a moment of existential crisis for Matt, a character already known (as a practicing Catholic) for his frequent wrestling with guilt and angst. Gone from this series is the lighter and more comical, yellow-suited Matt viewers enjoyed briefly in 2022’s She-Hulk: Attorney at Law.

The series asks us to consider whether we can truly escape our deepest motivations, the things that drive us to be who and what we are. In the remaking, do we reveal our actual selves? Both Matt and Fisk want to be ‘better’ than they were, but whether they can in such an imperfect world that both produces and rewards moral compromises becomes the through-line theme. Master criminal Fisk runs for and becomes the Mayor of New York City, and he does so at least in part with the sincere motivation of helping the city he loves to reach a place of safety, citing the growing presence of masked vigilantes as a symptom of NYC’s illness. No one in this political climate will miss the relevance of a felon gaining vast political power in part by finding scapegoats to blame for a supposed breakdown in law and order. But though Fisk may act with legitimate concern for the city’s welfare, he also manipulates the city’s government and political processes to serve not only his and Vanessa’s criminal empire but his internalized hatred for Daredevil and, by extension, all costumed heroes who work outside the system and therefore his iron control. Fisk’s innate need to dominate curdles his better impulses and by the series’ conclusion drives him to overtly license police brutality, stage a societal breakdown via cutting power to the entire city, and finally, declare martial law. As he notes to Vanessa, “I ran to serve the city, but…opportunities present themselves.”

Matt’s attempts to change are even more profound. His near-murder of Bullseye and the tragedy of Foggy’s death drives him to permanently eschew his Daredevil identity in favor of pursuing justice through more traditional means, within the established legal system. But the system is profoundly broken, prompting an inquiry into the role of superheroes in a world where the justice and political systems can be so corrupted that they no longer serve the innocent. Captain America: Civil War (2016) introduced, through the Sokovia Accords, the idea that powerful people might require institutional control to prevent mass casualties and destruction caused by their actions, but Daredevil: Born Again suggests a necessary role for extralegal protectors when the law or system fails. Of course that role is integral to the image of the superhero and has been at least since Superman’s debut in 1938, but it takes on a special significance now, at this moment in US history when social and economic inequality are at dismayingly high levels and police violence criminally so—should people with powers circumvent established avenues and become, as Fisk calls them, purposely using a loaded term, “vigilantes”? Matt over the course of the series returns to this question, at first fervently denying the necessity for a masked hero when the legal system he serves as an attorney is in place, but by the conclusion this denial has crumbled. The series shows audiences the reality of an unequal system in a powerful scene in episode 4 (“Sic Semper Systema”) between Matt and one of his indigent clients, who is angered by the unfairness of a structure that grinds up people like him and denies them dignity, autonomy, or fair chances at rehabilitation. And late in the series Matt returns to being Daredevil in order to stop serial killer Muse (Hunter Doohan), a murderer that Fisk’s cops cannot find. But the primary reason Matt finally accepts his inner drive to do right and protect the people of his city is Fisk’s weaponizing of corrupt elements of the NYPD by creating an Anti-Vigilante Task Force—ostensibly to capture criminals like Muse—that answers only to him. People sworn to serve justice willingly bow instead to corrupt power and give themselves over to Fisk in exchange for free reign to exercise brutality against perceived enemies of Fisk, the city, and themselves. Crises bring forth the heroes needed to fight them.

The ‘street-level’ Marvel heroes have almost always been set apart from the world-threatening or cosmic levels of narrative that dominate the MCU; though Matt during Daredevil’s Netflix years fought his share of faceless ninjas and a mystically resurrected Elektra, his most savage battles have always been against the ruthless and violent criminal appetites of the all-too-human Fisk. That dynamic is characteristic of the MCU in general, where the most chilling and emotionally complex villains have never been Thanos, or the Kree, or Cassandra Nova, but human beings with familiar motives such as Fisk, Kilgrave, “Cottonmouth” Stokes, or Erik Killmonger—people who operate (to a degree) on our own recognizable and relatable levels and utilize casual, up-close cruelty against fellow humans. That sort of ground-level intimacy also provides additional dimensionality to another of Daredevil’s concerns: the moral complexities of heroism. Like anything else, heroism can be a corrupting and corruptible idea: a number of NYPD cops in the series wear the skull insignia of their ironic folk hero the murderous Frank Castle/Punisher (Jon Bernthal), seeing Frank as a legend and a role model for stopping crime. These heroes of their own stories commit vicious assaults—including the shooting of masked hero Hector Alaya/White Tiger (Kamar de los Reyes)—even in the face of Frank’s clear and utter contempt for them. Despite Matt’s offering that Frank might truly be of service to people by saving lives, Frank knows himself and his broken nature, and is not nor ever will be a hero. But tragically, other people desiring to free their inner savagery will always find models on which to imprint, and can always weave false heroism out of selfishness.

The ‘street-level’ Marvel heroes have almost always been set apart from the world-threatening or cosmic levels of narrative that dominate the MCU; though Matt during Daredevil’s Netflix years fought his share of faceless ninjas and a mystically resurrected Elektra, his most savage battles have always been against the ruthless and violent criminal appetites of the all-too-human Fisk. That dynamic is characteristic of the MCU in general, where the most chilling and emotionally complex villains have never been Thanos, or the Kree, or Cassandra Nova, but human beings with familiar motives such as Fisk, Kilgrave, “Cottonmouth” Stokes, or Erik Killmonger—people who operate (to a degree) on our own recognizable and relatable levels and utilize casual, up-close cruelty against fellow humans. That sort of ground-level intimacy also provides additional dimensionality to another of Daredevil’s concerns: the moral complexities of heroism. Like anything else, heroism can be a corrupting and corruptible idea: a number of NYPD cops in the series wear the skull insignia of their ironic folk hero the murderous Frank Castle/Punisher (Jon Bernthal), seeing Frank as a legend and a role model for stopping crime. These heroes of their own stories commit vicious assaults—including the shooting of masked hero Hector Alaya/White Tiger (Kamar de los Reyes)—even in the face of Frank’s clear and utter contempt for them. Despite Matt’s offering that Frank might truly be of service to people by saving lives, Frank knows himself and his broken nature, and is not nor ever will be a hero. But tragically, other people desiring to free their inner savagery will always find models on which to imprint, and can always weave false heroism out of selfishness.

But more positively, Matt reframes the concept of hero to center it not around a single costumed figure, but as a collective popular phenomenon. At the series’ conclusion, with Fisk exercising draconian control over the city, Matt decides not to attack him in traditional superheroic fashion and, rather, begins to raise an army of resistance among the ordinary people of New York. Instead of a lone hero, he embodies a call to mass heroic action. As he says in his final words of the season,

I can’t see my city. But I can feel it. The system isn’t working. And it’s rotten. Corrupt. But this is our city. Not his. And we can take it back, together. The weak… The strong… All of us… Resist. Rebel. Rebuild. Because we are the city. Without fear.

Daredevil: Born Again argues that heroism is not, indeed, should not, be the province of a single powered individual (nor even an elite team like the Avengers), but the collective effort of people working together to resist corrupt institutions and to change them to better suit the societies those institutions were created to serve. One important detail of the series is that, more so than any other MCU production, it is marked by frequent shots of New York City streets and people, with frequent commenting (via the website reporting of BB Urich [Genneya Walton]) by New Yorkers about Fisk, Daredevil, and their own fears about/faith in the city. New York City and the people who make it what it is are equal participants in the series with Matt, Fisk, or anyone else. There is a popular sentiment in Daredevil that we have not yet seen in the MCU, and that sentiment and its concomitant social relevance gives the series particular significance. It should prove a profitable source of study for scholars studying the evolution of the superhero trope or those interested in the ways in which popular culture reflects and amplifies the concerns of our time.

Jeremy Brett is an archivist and librarian at Cushing Memorial Library & Archives, Texas A&M University. There he serves as Curator of the Science Fiction & Fantasy Research Collection, one of the largest of its kind in the world. Both his M.A. (History) and his M.L.S. (Library Science) were obtained at the University of Maryland, College Park. His professional interests include science fiction, fan studies, and the intersection of libraries and social justice.