Media Reviews

Review of Signalis

Bryn Shaffer

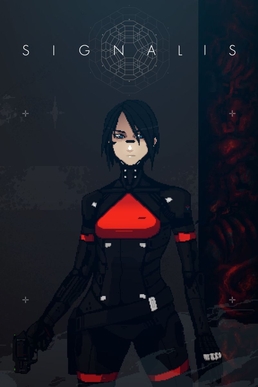

Rose Engine. Signalis. Humble Games and PLAYISM, 2022.

“Achtung. Achtung.” The first line of Rose Engine’s 2022 science fiction survival horror game Signalis isa distress signal repeating a single German word over an interstellar radio, flashing over a dramatic glitching red CRT screen. The opening is an obvious deep space horror trope meant to denote the game’s membership in the lineage of other SF and survival horrors such as Alien Isolation, Dead Space, and Silent Hill. However, it’s not long before this genre allusion is betrayed. Signalis proves through its referential prowess and surrealist mechanics as not only an SF survival horror, but a psychological text that challenges the delineations of genre, and engages with transmedia cultural, historical and philosophical discourses on the nature of personhood, death, and memory. The game opens with the player journeying out from a crash-landed spaceship into a strange deep hole in the ground where a nightmarish mining facility spirals impossibly deep into the earth and the laws of time and space become distant memories. As the title cards flash, so do lines from Chambers’ The King in Yellow,a shocking rendition of Bocklin’s painting The Isle of the Dead, and several lines from Lovecraft’s The Festival. The message the developers telegraph with this intensely convoluted yet beautifully referential introduction to the game world is clear: this game is not what you think it is. Achtung. Achtung. Danger. Danger.

Signalis is set in a dystopian future where humanity has spread across the solar system under totalitarian militaristic rule. Even in deep space, the long tendrils of fascism exert their crushing grip on the last vestiges of humanity and its replicas. The player follows one such “Replika”, Elster, an android created using edited memories copied from a long-dead human. The plot follows her on a nightmarish cosmic journey after her ship, the Penrose, crashes and its only other inhabitant goes missing. Most of the game takes place in the strange underground government mining facility stuck in a dreamy time loop that shifts to reflect the repressed memories of Elster, her originator, and her missing friend. The developers have woven themes of identity and memory throughout the game world and many have speculated the plot itself is a living memory, an existential crisis, or the melting dreams of an artificial being whose concept of ‘self’ is coming apart at the seams. The possibilities for exploring the notion of personhood are plentiful, and Signalis knowingly presents these themes at the forefront of its game world inviting speculation meant both to enhance the player’s experience and to incite a deeper consideration of the genre themes at play in games centered on artificial protagonists.

The game’s survival horror mechanics are directly reminiscent of Resident Evil and Silent Hill—a limited 6-item inventory, a stash box only found in safe rooms, a sprawling puzzle-filled map requiring continuous doubling back and detailed exploration, and enemies that deal high damage compared to your very limited health. Stealth, exploration, survival and purposeful confusion are the driving forces of play. These classic mechanics weave expertly alongside a story of surreal complexity that requires a constant re-exploration of the environment, and a science fiction setting that blurs the lines between the possible and the otherworldly. In the era of infinite inventories and mechanics that encourage larger and larger amounts of time spent in menu optimizing status over in world exploration, Signalis’restrictive inventory system is a refreshing callback that forces the player to stay in the scary enthralling game world and boosts rather than breaks immersion.

Interspersed throughout the story are interactions with literary works that at first glance seem out of place in the science fiction world, but which upon further examination serve to situate the game within genre traditions of cosmic horror and the problematic nature of some of the genre’s more historically prominent creators. It is likely no coincidence that the player is invited into the deeply fascist dystopia of the mining colony with the words of HP Lovecraft and Robert W. Chambers, authors whose prominence gave rise to the cosmic horror and weird fiction literary genres, and who in equal measure were notorious racists who wielded white privilege to enable their rise to literary fame. Working in cosmic horror has troubled creators for generations: how do we reconcile these deeply problematic authors with their contributions to the genre and all it offers as a space for creative and horrific expression? Here Signalis gives us an engagement with cosmic horror that future developers should note—treating these ‘fathers’ of cosmic horror as themselves horrors. Where it could have been easier to make cursory allusions to the cosmic horror genre in the setting of Signalis using similarly aligned aesthetic tropes, Rose Engine has made a concerted effort to engage with the authors themselves in the game world, framing these works as fascist, hellish, and problematic objects that trouble the player, protagonist, and NPCs alike.

Mechanically, Signalis is definitively retro-tech. From the HUD and UI to the limited player mechanics, to the creation of a gameworld where analogue technology dominates over digital, the metallic and plastic clicking and clacking of mechanical interaction are a key element of the game’s design and play well with the game’s use of low poly modeling. Although the game is cross-platform, it is best described as a PlayStation 2 throwback. This is common in many retro-style survival horror AA games that seek to emulate the Silent Hill and Resident Evil style, Another comparable release much like Signalis in its recreation of this look and feel is Headware Game’s 2024 Hollowbody which likewise relies on a limited inventory, low poly modeling, fixed camera angles and surreal horror elements. Even though the developers likely wanted to re-create the visuals of the bygone era of 2000s survival horror, the graphics of the game also speak to the developers’ ability to write an intriguing story. Where modern AAA releases rely on ‘good graphics’ and impressive animation, Signalis pulls off the same impact with low graphics fidelity and uncomplicated mechanics. What keeps the player entranced in this retro space is the strength of how the retro technical look plays into the expertly crafted storyline and atmosphere, which is only enhanced, rather than undercut, by the limited and vintage quality graphics. This is perhaps one of the reasons for the current appeal of the early 2000s or Playstation 2 era survival horrors: a desire to push back against the supplanting of well-written and truly surrealist stories with impressive visuals as seen in the AAA industry, and instead return to narrative-driven horrors that work with what technologies are available to tell compelling stories.

Perhaps most impactfully is Signalis’engagement with an array of musings and histories related to death and dying. Arguably, we can consider the entire story as one drawn-out death played and replayed through memory in the mind of two decaying minds clinging to each other in the depths of space. More specifically, within the facility, death constructs both the environment and actions of the NPCs—Replikas wander the halls in a zombie-like state, molding, and slowly crumbling. The walls of the facility bleed and turn from metal to cancerous flesh over time. It’s no coincidence the developers chose Japanese as one of the dominant surviving cultures and languages in their distant society, with their depiction of mass death in the facility often showing ashen shadows of bodies imprinted on walls and floors, calling to mind the tragic imagery of victims of nuclear fallout. Bocklin’s Isle of the Dead is not only a painting found throughout the game, but makes its way into the game as a location visited by the player, inviting us to situate the game alongside the symbolist tradition of depicting death through lenses of oblivion and the surreal. At one point the player explores a literal hellscape, and encounters rituals of death and funeral whose names are long lost. Through and through death lingers over the entirety of Signalis,keeping it unrelentingly on the mind of the player.

Signalis is a challenging game, not only because its mechanics are unforgiving, its puzzles challenging, and its environment deeply upsetting, but because it demands a level of analytical, philosophical and historical engagement the player may not anticipate from a Playstation 2 homage. However, Rose Engine’s work is worthy of playing, and replaying, as it offers multiple points of entry for analytical engagement and is unique in both the survival horror and science fiction genres. Overall, Signalis is a work that delivers on the key elements of both deep space horror and retro survival horrors, is an expert return to 2000s aesthetics and modes of play, and layers in unique and compelling storytelling that touches on themes of personhood, death, and memory in completely unexpected and deeply evocative ways.

Bryn Shaffer is a graduate student at the University of British Columbia School of Information, where she holds a SSHRC award for her thesis work on information video games, and is an ALA Spectrum BIPOC scholar. Her research interests are in video games, HCI, horror and capitalism and labour studies. When she isn’t writing her thesis, she’s writing video game reviews and essays for the internet, or playing video games with her cat Salem.