Media Reviews

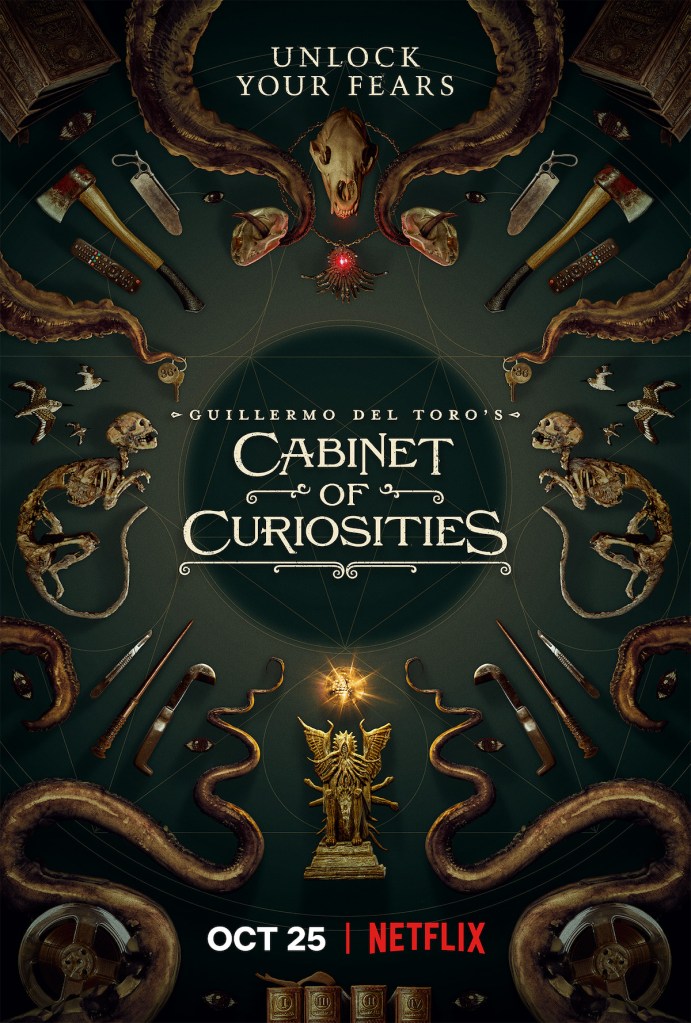

Review of Guillermo del Toro’s Cabinet of Curiosities

Alice Fulmer

Guillermo del Toro’s Cabinet of Curiosities. Guillermo del Toro. Netflix, October 2022.

In the late 70s-tinged seventh episode of illustrious writer-director and auteur-tastemaker Guillermo del Toro’s Cabinet of Curiosities, “The Viewing”, we are innocuously introduced to the anthology’s thesis. Upon being asked ‘what was the best song you ever heard?’ by his insidious host Lional Lassiter (Peter Weller), comedian Eric Andre’s blaxploitation-esque, funk troubadour character Randall pensively remarks that, “1969. I’m in Greece and I … fall in with these freaks making psychedelic music. One of them played this song one night. Never been recorded, something they knew. It made me nostalgic for things that never happened”. This is also the perspective we are invited to share as an audience—beholden to del Toro’s series of hauntological, liminal spectacles which are scripted, animated, performed, recorded, and or otherwise “things that never happened”

At the helm Cabinet of Curiosities coming from the same director of Cronos (1992) and Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), it should be no great surprise then to see how or why classical motifs collide with Victorian ghosts, microwaveable hot wings, or deep cuts from the 20th century’s speculative fiction and horror to create an anthology rich with anachronistic gestures. These selections range from H.P. Lovecraft (1890-1937), Henry Kuttner (1915-58), and Michael Shea (1946-2014), as well as adaptations (or teleplays thereof) from del Toro himself and contemporaries like Panos Cosmatos and Emily Carroll. This anthology series creates a different dialectic of aesthetics and mores while paying homage to many of del Toro’s formative influences. Perhaps it is for the best that he is not looking through rose-tinted glasses to Lovecraft—tempting as it may be for any fan of horror, sci-fi, and related genres. Instead, the show’s relationship to nostalgia is complicated.

For Randall, nostalgia—whose inception in ancient Greek poetry was characterized as Odysseus’s longing for home—appears in contrast to the German fernweh, “far-sickness”, or in more archaic English, “far woe”. For a horror hound audience this is a devastating conclusion because del Toro’s manipulation of nostalgia and its oppositional forces like fernweh is what not only drives the aesthetic overtures of Cabinet of Curiosities, but uses the audiences’ sentimentality against them. This tension is central to the series. His take on the gothic, macabre, and the monstrous is pointedly different from other anthology series that have been quick to cash in on their own self-referential nostalgic tropes. Ryan Murphy’s American Horror Story, for one, though pioneering in several different ways including a stellar inclusion of LGBTQ+ talent, is guilty of producing seasons and storylines that cannibalize past ones in the name of early 2010’s tumblr nostalgia for the first three seasons. While Cabinet of Curiosities so far seems to just be a standalone season, its internal and nearly randomized structure precludes anything like its immediate predecessors (or future competitors)—one of the shows’ many strengths.

In terms of nostalgia’s embodiment, there is more represented than just the ‘specter’ that Derrida posited from Marx’s sediment in the opening lines of The Communist Manifesto (1848)– —Cabinet of Curiosities presents visceral alternatives. This is seen plainly in “The Autopsy” as well as “The Murmuring”—literally parasitic in the former and neurodivergent ruminations in the latter. The alien forces entering the miner’s bodies in “The Autopsy” need human bodies to demonstrate their vision of humanity’s future. And as the episode crescendos, their argument about their natural embodiment versus the humans they ‘possess’ is as convincing as it is unsentimental. This is not unlike the motion towards the bodies of the dead as resources in “Graveyard Rats” by Masson. In both instances, the script propels the viewer to sympathize. But from overhead in both episodes initially evoked here (or rats underground, for “Graveyard Rats”), nostalgia strikes back. At the climax of “The Autopsy”, Dr. Winters (F. Murray Abraham) reaches for the scalpel just off the exam table and kills the alien inside Allen (Luke Roberts).

Similarly, from overhead in “The Murmuring”, it is only after Claudette’s (Hannah Galway) apparition is carried off by a classic of (folk) horror, a huge flock of birds, that Nancy (Essie Davis) can confront the pushed back grief of the loss of her only child Ava with her husband, Edgar. The grieving has been subdued by them both—and from the onset of the episode the marriage appears both unromantic and anti-nostalgic. Their internal and external grief’s dam is filled given the release of catharsis through the parallel ghost train that Nancy is witness to over the course of the episode, spanning the events of Claudette’s son being drowned and her subsequent suicide. Her husband, however, is not privy to this. Nonetheless, both episodes end optimistically if but on the precipice of confession—the alien plot will be unfoiled from a tape recorder in Dr. Winter’s lab and Nancy wants to talk to Edgar about the feelings surrounding their daughter’s death—and perhaps revive a ghost of their own lifetime: an emotionally open and vulnerable marriage.

Furthermore, Guillermo del Toro’s Cabinet of Curiosities as an anthology series resists easy classification, and the manipulation of nostalgia and fernweh can be argued to operate on an uneasy hauntological fulcrum that even contests the arguments of Fisher. Mark Fisher lamented in his 2012 “What is Hauntology?” that, “The future is always experienced as a haunting: as a virtuality that already impinges on the present, conditioning expectations and motivating cultural production. What hauntological music mourns is less the failure of a future to transpire—the future as actuality—than the disappearance of this effective virtuality” (Fisher, 16). These cultural theories on hauntology are useful to highlight the series’ often contradicting and (not but) multivalent takes on sentimentality and temporality. Consider the second episode, “Graveyard Rats” and the sixth, “Dreams in the Witch House”, and their attitudes to the departed. In the former, the cadavers of the mortuary and those already buried in the nearby cemetery (and their valuable belongings) are bargaining tokens for the intrepid graverobber Masson’s (David Hewlett) conflicting Protestant work ethic and theological guilt: how can a graverobber go to Heaven? If this rhetorical question stands in doubly as a set up for a joke, a punchline may roll out as “He gets buried alive”. His rationalization of graverobbing for profit disrupts the sentimentality around burial within the wider Christian tradition, burying any guilt accrued from religious or scrupulous guilt—a haunting which remains unresolved as he is exhumed in the same grave he dug, eaten alive by rats and discovered sometime later by other graverobbers.

Conversely, “Dreams in the Witch House” has a disruption of the dead that is heavily and/or overly sentimental: researcher Gilman’s (Rupert Grint) teleological drive to ghosts, spirits, séances and other antiqued Spiritualist ephemera is endemic of unresolved trauma over his twin sister’s childhood death. His obsession to re-animate her body becomes the de-animation of his own. It is worth noting that this episode is based on a Lovecraft short story originally a part of the Cthulhu Mythos—an embedded narrative whose inclusion would not fit the scope of this series at all because of the Mythos’ own concepts of continuity. So instead, our protagonist is situated in the 1930’s at the end of the Spiritualist movement. This framing is emblematic of the series writ large, and how it deals with the pernicious afterlives of its socio-cultural subjectivities. This contrasts with Fisher’s conceptions of hauntology (Derrida’s notwithstanding), which necessitate the need for a haunting to come within one’s lifetime.

The Spiritualist movement and its aesthetics no doubt ‘haunt’ our understandings of ghosts and the corporeality (or lack thereof) of the dead in media. Tarot cards, deliberate conjuring of the dead, and uncanny salons, galleries and basements are all in the backdrops of several episodes. This hallmark set of aesthetics is not only showcased in del Toro’s Cabinet of Curiosities, but in contemporary adaptations of media which depict the dead made before the peak of Spiritualism circa the latter half of the 19th century. The “Dreams in the Witch House” not only lampoons the decline of Spiritualism (nearly ‘dead’ by the 1930’s), it dispels that conjuration ‘fixes’ the past or that lofty aims to revive the dead are conducive to the human condition of grief. For our cultural moment that is rife with a renaissance in astrology, tarot, and practices this take is refreshing. Cabinet of Curiosities does not deny the existence of ghosts, hauntings, or even aliens—it does affirm though that there are several approaches, materialist or “Spiritualist”, to how nostalgia is processed as an inhibition or disinhibition for characters like Gilman.

From my scholastic methods used to conduct this review, these three episodes—“Lot 36”, “Graveyard Rats”, and “Pickman’s Model”—did not manipulate sentimentality, nostalgia or fernweh effectively and sparingly used the dark, macabre, hyper temporalities and realms that lies at the heart of del Toro’s work. This is evidenced from the episodes’ near-unison clamor on the locus of the archive—be it a storage unit (“Lot 36”), cemetery underground (“Graveyard Rats” or even an art gallery (“Pickman’s Model”)—these are dangerous places that will eat you alive if given the chance. From a theoretical point of view, Fisherian hauntology may offer some potential answers as to how and why the hauntings are constructed and conceived.

WORKS CITED

Fisher, Mark. “What Is Hauntology?” Film Quarterly, vol. 66, no. 1, 2012, pp. 16–24. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.2012.66.1.16.

Alice Fulmer (she/her) is an MA/PhD student at the University of California, Santa Barbara, educator, and poet. She is pursuing a Medieval Studies emphasis, and planning a prospectus on disability and gender in the Canterbury Tales. Her debut collection Faunalia (2023), is available from Ritona Press. Aside from reviews in SFRA Review, other academic publications include an article on Sir Launfal (c. 1400) in UCLA’s Comitatus. In February 2025, an arts & comedy podcast co-hosted by her and graduate students, Cunterbury, will debut on all major podcasting platforms.