Media Reviews

Review of Godzilla Minus One

Jeremy Brett

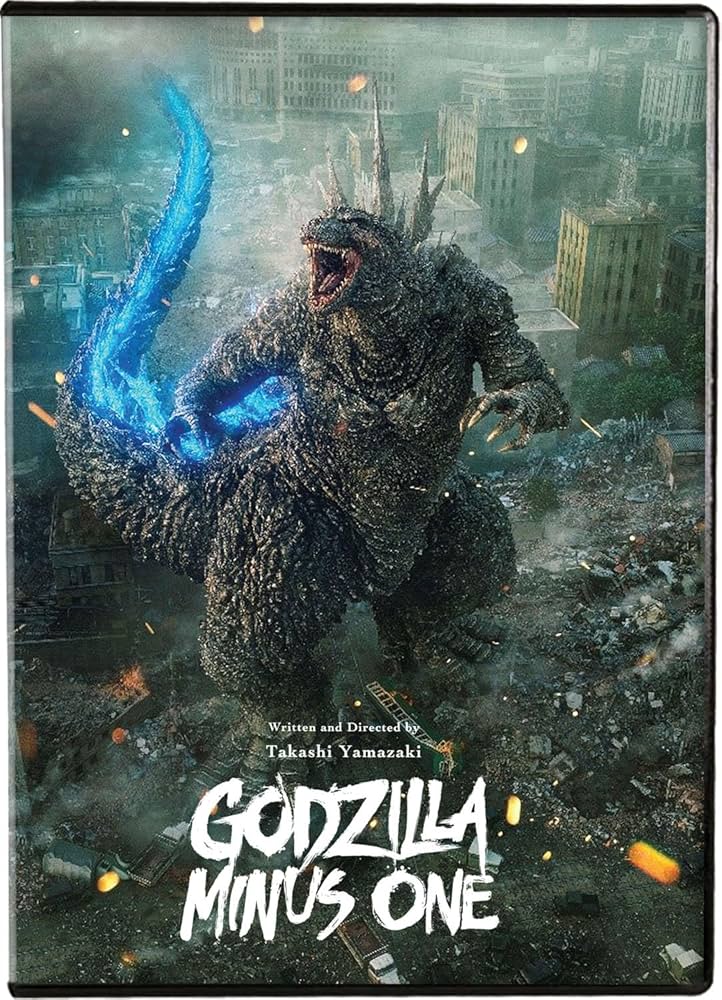

Yamazaki, Takashi, director. Godzilla Minus One, Toho Studios, 2023.

Scholar and translator Jeffrey Angles notes in his recent translation of the original Shigeru Kayama Godzilla novellas, that Kayama used the massive, irradiated reptile as a driver for suggesting that “humanitarian values, especially when coming from the postwar generation, will be what Japan needs,to guide the country through its ethical dilemmas” (Angles, 215) That observation could just as equally apply to the 2023 film (and most recent franchise reboot) Godzilla Minus One, in which the realization of ethical commitment to a new future, to a new generation, is brought to bear by a traumatized and shaken population emerging from complete catastrophe. Godzilla’s use as a metaphor for the atomic bombings of Japan and the existential fear of nuclear war is already well-known, but much of the genius of Godzilla Minus One is an explicit coupling of that to the deep trauma produced by the American firebombing of Tokyo and immense conventional destruction levied against a civilian population in the course of war. The people of Tokyo near the end of World War II did not experience an atomic attack, but no less than the populations of Hiroshima and Nagasaki suffered incomprehensible loss and the end of everything and everyone they knew, believed, and loved. It is in the aftermath of that loss that Godzilla arises. The 37th film in the Godzilla franchise—and the 33rd by Toho Studios—Godzilla Minus One strips away layers of backstory, titanic battles between kaiju, and many of the traditional Godzilla tropes, to create an ultimately simpler story of character and the ways in which humans not only process and learn to cope with shock, but transform it into constructive, beneficial action.

Both the trauma of war and the human failure war signifies suffuse the entire film, centered on pilot Shikishima Koichi (Kamiki Ryunosuke). At the very end of the war, Koichi lands his plane at a garrison on distant Odo Island, claiming technical problems. Mechanic Tachibana Sosaku (Aoki Munetaka) quickly realizes Koichi’s true motive—to avoid fatal service as a kamikaze; a realist, Tachibana supports Koichi’s choice to live in a world when the outcome of the war is patently obvious. But war, in the person of Godzilla, is not done with Koichi; the monster rampages through the garrison, which is decimated after Koichi freezes in terror and fails to turn his plane’s gun on Godzilla. Once Godzilla departs, only Koichi and a wounded, enraged Tachibana are left amid the bodies and the wreckage. In an example of Godzilla’s ongoing metaphorical shifting throughout the film (and, indeed, the franchise), Koichi cannot escape modern war’s destruction, which knows no limit and which indiscriminately creates victims, no matter how hard he tries or how remote the location to which he flees. War, like a giant monster, is relentless in its progress. The film, interestingly, presents a monstrous and deadly Godzilla from the outset—the 1946 US atomic bomb tests that in previous incarnations of the franchise create Godzilla, here simply amplify him, both in size and destructive capability (i.e., his radioactive heat ray); Godzilla Minus One suggests that war to a great extent is only a continual evolution towards greater and greater harm, but that in some form has always been a part of the human experience.

Koichi returns to a devastated, defeated Tokyo, carrying only the family photographs of the men on Odo for whose deaths he feels responsible. The scenes set in the ruins of the city are powerful in their presentation—a once-thriving capital is a place of shacks, shanties, food lines, and the ghosts and memories of the countless dead slaughtered in the firebombings. The dead include both Koichi’s parents and the children of his embittered neighbor Sumiko (Ando Sakura), who rages at Koichi for not having sacrificed himself as his duty to try and save the nation. Her reaction only compounds his survivor’s guilt, yet he discovers a motive for living when he encounters Oishi Noriko (Hamabe Minami), a young woman, left utterly alone, carrying baby Akiko (played by Nagatani Sae as a toddler) through the ruined streets. By 1946, the three have become a found family (overcoming Koichi’s terror of closeness and its concomitant risk of loss), imagining the possibility of hope and renewal, both on the personal and the national level. The strength of human connection proves powerful even in the face of existential oblivion—when Koichi tells Noriko he has obtained risky work on a ramshackle boat charged with destroying American mines, she grows furious and terrified, ordering Koichi not to get himself killed.

The minesweeping crew represents different elements of the postwar Japanese generation—

Koichi, the traumatized veteran, wracked by guilt-ridden nightmares of Godzilla; Noda Kenji (Yoshioka Hidetaka), the former weapons designer wrapped in his own introspective remembrances; Akitsu (Sasaki Kuranosuke), the cynical captain bitter at his government’s history of using and silencing the common man; and Mizushima (Yamada Yuki), too young to have seen service but anxious to prove himself. Akitsu counterbalances Mizushima’s youthful enthusiasm, telling him at one point, “To have never gone to war is something to be proud of.” Following reports of Godzilla sinking American ships, the crew are posted with orders to stall the monster until naval reinforcements arrive. Their encounter with Godzilla reveals his new mutations—increased size, deadly heat ray, and his regenerative powers that let him rapidly recover from both naval artillery and a mine jammed into his mouth and then exploded by gunfire from Koichi. But this defeat proves a turning moment for Koichi in his journey towards redemption. In a desperate plea to Noriko that he be able to “put all this to rest”—his guilt at being alive at all—she responds, “Everyone who survived the war is meant to live.” Koichi gains newfound purpose and determination; he is reconstructing himself just as the Japanese nation has begun to reconstruct itself after the war, just as the Ginza district of Tokyo, where Noriko now works, is busily rebuilding itself. A new and horrific attack by Godzilla on the city, though, levels much of Ginza, kills 30,000 people, and apparently kills Noriko just after she pushes Koichi out of the way of the blast wave caused by Godzilla’s heat ray. Koichi is left with a renewed sense of trauma and guilt, castigating himself for daring to try and live when his redemption remains unfulfilled.

At this point, the film begins to center on a collective popular effort to stop Godzilla from returning to Tokyo; the struggles of the Japanese people as a whole become signified by a concerted endeavor by men at the lower end of the social order to save their nation. Unlike previous Godzilla films, there are no labs full of white-coated scientists developing high-tech solutions to eliminate the monster, only Noda putting together a desperate plan to entrap Godzilla with freon gas and destroy him via rapid underwater descent and reascension. There are no masses of generals and other officers in war rooms and bunkers planning stratagems and massive responses, only a single former naval captain, Hotta (Tanaka Miou), asking for former naval personnel as volunteers to steer four disarmed destroyers into harm’s way. There is no help coming from either the Japanese government, which has no resources to muster, or the occupying Americans, who fear military action might antagonize the Soviets—in this, Tokyo’s desperate hour, victory and the end of years of prostration will come through the mutual efforts of ordinary men—navy veterans, engineers, and tugboat crews. Years of feeling betrayed by a neglectful and abusive government, and without agency in a newborn world, are to be superseded by a chance at preserving, not taking, life. As Noda says to the assembled group of volunteers the night before the attack,

Come to think of it, this country has treated life far too cheaply. Poorly armored tanks. Poor supply chains resulting in half of all deaths from starvation and disease. Fighter planes built without ejection seats and finally, kamikaze and suicide attacks. That’s why this time, I’d take pride in a citizen led effort that sacrifices no lives at all! This next battle is not one waged to the death, but a battle to live for the future.

The hope of a better world becomes the engine driving the war against Godzilla, who represents at this one moment both the endlessly destructive past and the potentially devastating atomic future

—Godzilla Minus One posits that the legacy of the one and the looming danger of the other are effectively countered only by a common human effort, one that looks unselfishly to what might come after. As the volunteers, including Noda and Akitsu, board their ships, Mizushima—enthusiastic to help—is purposely left behind; over Mizushima’s protests, Akitsu mutters, “We leave you the future.” Stopping Godzilla has transformed from the simple killing of a monster into, instead, a dramatic step in the process of Japanese societal rebirth and restructuring, and another progression towards exorcising the trauma of war. It is an emotionally resonant return to the original postwar ethos of the Godzilla saga –a turn away from the frequent positioning in the series of Godzilla as Japan’s protector rather than its destroyer and back towards his symbolic image as the terrible power of war and nuclear destruction. (The film also, I note, supplies a psychological complexity and thematic value absent from the recent American “Monsterverse’ Godzilla series, which would rather ape traditional disaster movies and add unnecessary backstories than confront the real human traumas and costs inherent to Godzilla.)

Koichi also finds in this battle his own restoration, and an end to his crippling guilt. He pilots a late-war experimental fighter to lure Godzilla into position in Sagami Bay—the plane is repaired by Tachibana, one of the ghosts of Koichi’s past, reconciliation with whom is vital to Koichi’s healing process. And before Godzilla can use his heat ray to eliminate the volunteer fleet, Koichi flies the bomb-filled plane directly into Godzilla’s mouth, destroying him from the inside. He survives because Tachibana had installed an ejector seat, demanding of Koichi that he must put aside his guilt and live. And so, Koichi does, indeed, live, having given himself, his adopted daughter Akiko, and his nation, a new chance for life. It is telling that the film’s final line of dialogue, from Noriko (who has survived and is in hospital) to Koichi, “Is your war finally over?”, references the psychological struggles that have defined him, his friends, his country, and, indeed, the film as a whole. What Godzilla, a monster whose metaphorical nature has been a fundamental part of the character since his 1954 inception, represents in this impressive and striking film above all is the collective ordeal of the Japanese wartime and postwar experience. That trauma is both a shared experience and shared uniquely by each individual Japanese; much of the strength of the impressive Godzilla Minus One comes from its recognition of the psychological journeys that both societies and individuals take in overcoming guilt and trauma inflicted by the vagaries of catastrophic war.

WORKS CITED

Angles, Jeffrey, translator. Godzilla and Godzilla Raids Again. By Shigeru Kayama, University of Minnesota Press, 2023

Jeremy Brett is a librarian at Cushing Memorial Library & Archives, where he is, among other things, the Curator of the Science Fiction & Fantasy Research Collection. He has also worked at the University of Iowa, the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, the National Archives and Records Administration-Pacific Region, and the Wisconsin Historical Society. He received his MLS and his MA in History from the University of Maryland – College Park in 1999. His professional interests include science fiction, fan studies, and the intersection of libraries and social justice.