Fiction Reviews

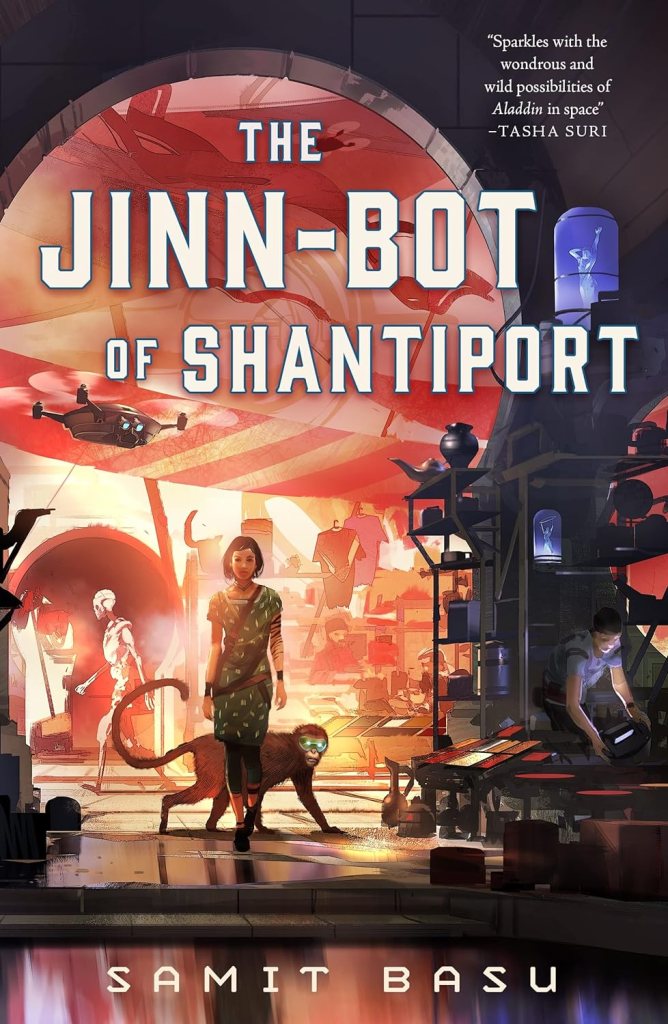

Review of The Jinn-Bot of Shantiport

Jeremy Brett

Harrow, Alix E. Fractured Fairy Tales: A Mirror Mended. Tor, 2022.

Beneath the guise of a futuristic, expansive retelling of the Aladdin story, The Jinn-Bot of Shantiport is a thoughtful examination of the right of every sentient creature to assert its own identity. The Capekian narrative heritage that concerns itself with the subjective existence of robotic autonomy moves through the novel as fiercely as the characters—artificial and human alike—travel through the busy streets of the decaying, lively city of Shantiport. Furthermore, the novel links the contention over the rights and dignities of who and what we determine to merit them to conscious choices about what families we choose to create and populate. These are evergreen human concerns with a venerable fantastical tradition, of course; Basu here infuses them within a story of mechanized kaiju fights, political and corporate corruption, monarchical intrigue, and the possibilities of new human and robotic futures should beings choose to rethink their existing political and economic structures.

Shantiport is a sprawling and failing once-great city on an unnamed planet where the majority of the population lives and labors under the governance of the ruthless Tiger Clan, a rule counterbalanced by the influence of acquisitive billionaire Shakun Antim. The city is in an existential crisis, with rumors of its gradual and unstoppable sinking running rampant. Into this morass come three protagonists: thieves making their way through first, a quest for a mysterious alien object with limitless potential and, second, a reconceptualization of not only their personal priorities but their relationships to one another as thinking beings. Lina and Bador are very different siblings. Lina, the child of former revolutionaries, hopes for dramatic positive change to her beloved city. Bador, by contrast, is a monkey-shaped cyborg construct with limitless ambition and confidence, a trickster and mischief-maker determined to make his own future and equally so to enforce among his family his sense of self and belief in the independence and freedom of bots in a human world. Bador, created by Lina’s parents, and Lina think of each other as siblings, but Bador balances his intense sense of self-worth with bitterness at his subordinate societal position and the objectification of bots in Shantiport life. As the novel’s narrator and third main character Moku—himself a piece of alien tech, a drone-like sentient bot—observes of Bador,

It’s the casual assumption of human supremacy that upsets Bador most, every time… Bador’s dream is about bot rights. A world where bots and intelligences aren’t just treated as people by humans who are nice, but guaranteed equals in a society by law. By systems. He knows the details are complicated…he’s aware that bot rights are an impossible dream right now and he is willing to wait for change, and to kick an incredible amount of ass while waiting. What he doesn’t see is why Lina’s impossible dream is more important than his. And honestly, I don’t either. (131-132)

Lina seeks an utter end to the oppressive and corrupt power structures that control Shantiport, a nonviolent end that will also institute social equality. It’s a vision that, indeed, seems at least as unreachable as Bador’s, and just as important, but Moku asks a legitimate question: whose priorities in bettering society must take precedence? And by extension, a vital argument about human nature takes shape: Who among us has value in the world? Bador is fully aware that his acceptance by Lina and her mother/Bador’s co-creator Zohra is not absolute, but contingent on their own security needs (Bador knows he is not told everything by them, because they fear the Tiger Clan could capture him and read his thoughts). It is hard in Bador’s situation not to see similarities to underrepresented groups in the real world whose societal progress is frustratingly constrained by conditional white support.

Another major source of conflict in the novel involves differing opinions over how political reform is most effectively accomplished. The titular jinn-bot, Lina learns, is a piece of tech with nearly boundless power to manipulate technological reality, something it grants to its users via the traditional ‘three wishes’; Lina and Zohra resolve to bring justice and order to their beloved Shantiport, but whereas Lina wants to use the jinn-bot for immediate and dramatic change, the former revolutionary Zohra prefers incremental, safer reform with fewer chances for catastrophe or unforeseen consequences. As Lina says, “You want to use him [the jinn-bot] for small bursts of advantage, not disturbing the overall equilibrium, or drawing too much attention…we should use the jinn to solve the problems we are unable to solve ourselves, systemic problems, multigenerational problems, worldwide problems that somehow humans have bene unable to solve for millennia” (195). A suspicious Zohra responds that the jinn is not a magic wand, but an unknown technology with unidentified interests, furthermore noting “for the society we want to build, self-governance, optimal representation and participation, nonviolence, sustainability, and operational expertise are nonnegotiable. Tech cannot give us that, no foreign intelligence can…humanity’s surrender of its own agency to algorithms and oligarch-owned tech has brought us to the brink of absolute ruin” (196). Influenced by decades of experience, Zohra would promote small societal adjustments and attempts at human consensus, whereas Lina would prefer acting broadly and without the intervention of fallible, argumentative human beings while the chance exists. It is an incredibly relevant debate for this particular historical moment, where we face any number of political crises and well-meaning people disagree on the need for slow vs. radical ways of thinking and acting, and where the increasing presence of AI and other technologies in our lives increases our dependency. Here Basu joins authors such as Kim Stanley Robinson, Malka Older, Ursula K. Le Guin, and others who use SF as an imaginative political space where arguments about necessary ways of governing play out within a fantastical atmosphere.

At its core, The Jinn-Bot of Shantiport is an examination of the ways by which we perceive each other’s relevance to the greater society around us, as well how those perceptions contribute to the communities and identities we try to build for ourselves. Our destinies, both individual and societal, can never truly be reached until we make the decision to understand and accept the worth of every sentient being, including our own. At one point, Bador and Moku are speaking with Tanai, the interstellar ‘space hero’ who has arrived at Shantiport for his own mysterious purpose. Bador confesses to him his doubts about his nature being ‘natural’ or ‘unnatural’, and Tanai provides a heartfelt, intensely humanist response suffused with respect for the autonomy of all people, artificial or otherwise: “If it helps, know that nothing about you is unnatural…I have seen this in many worlds – people who believe some aspect of their nature, or their person, justifies their exclusion. You exist, and you deserve to belong. You are a part of nature, just as much as I, or a tree, or a rock, or even a plastic square. And anyone who told you otherwise is no friend” (269).

Jeremy Brett is a librarian at Cushing Memorial Library & Archives, where he is, among other things, the Curator of the Science Fiction & Fantasy Research Collection. He has also worked at the University of Iowa, the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, the National Archives and Records Administration-Pacific Region, and the Wisconsin Historical Society. He received his MLS and his MA in History from the University of Maryland – College Park in 1999. His professional interests include science fiction, fan studies, and the intersection of libraries and social justice.