Media Reviews

Review of They Cloned Tyrone

Jess Flarity

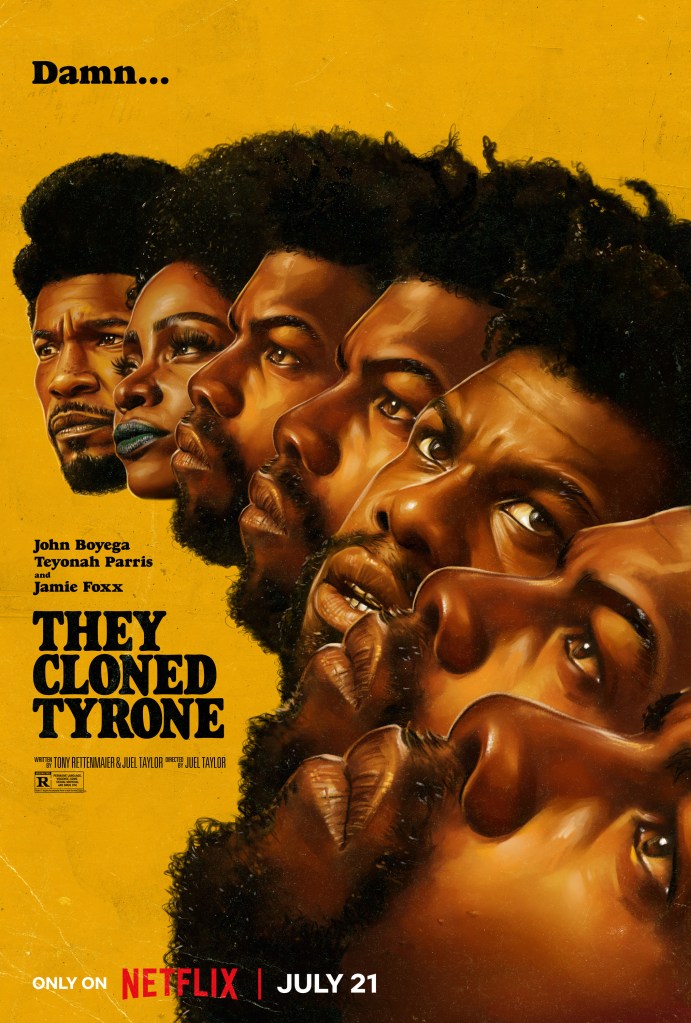

They Cloned Tyrone. Dir. Juel Taylor. MACRO Media, 2023.

They Cloned Tyrone is an American Afrofuturist film centered around consumerism, systems of inequality, and governmental distrust. It’s unfortunate that the film released only on Netflix at the same exact time as the Barbenheimer phenomenon in the summer of 2023, denying the movie the same name recognition as Get Out (2017) and Sorry to Bother You (2018), as it belongs firmly into a new genre that has been called Afro-Surrealism (Bakare). Director Juel Taylor frames They Cloned Tyrone in a blend of science fiction, humor, and campy callbacks to the blaxploitation flicks of the late 20th century, rather than relying on the horror elements favored by Jordan Peele or the bizarro Black absurdism of Boots Riley. This results in something like a sleeker version of Undercover Brother (2002), though the satire elements don’t push as far into parody as Black Dynamite (2009). Taylor has also cleverly interspersed easter eggs and callbacks throughout the film (Moore), but despite its unique setting and fantastic acting from all the main characters (including John Boyega as a drug dealer, Jamie Foxx as a pimp, and Teyonah Parris as a prostitute), this review will focus more on the racial themes present throughout its plot, which are crucial for understanding its science fictional premise. To briefly summarize, the movie is about this unlikely trio discovering that their neighborhood is part of a secret government program to keep Black communities subjugated through the use of mind-control drugs—clones of key people in the neighborhood are unaware they are pushing the drug.

This film is the first-time feature of Taylor, who wrote the script with Tony Rettenmaier, and was clearly influenced by his upbringing in Tuskegee, Alabama (Ugwu). Taylor grew up in the same neighborhood where the hideously unethical USPHS Syphilis Study took place, as 600 Black men were experimented on by the U.S. government to study the results of untreated syphilis from 1932-1972 (Tuskegee University). Though Taylor does not directly mention this study in any interviews, the Philip K. Dickian levels of paranoia experienced by the protagonists must have stemmed from all the conspiracy theories he heard growing up, which ranged from college sports scandals to fears about fluoride in toothpaste (Haile). Many science fiction fans will notice that the story has elements of Groundhog Day (1993), The Truman Show (1998) and The X-Files (1993-2018), though Taylor has also stated that he wanted it to feel more like a haywire episode of Scooby Doo, which explains its more comedic elements. Because of this lighter tone, the hard science and thought experiments concerning the moral paradoxes and social impacts of cloning are mostly bypassed, which may be disappointing to those who enjoyed the plots of movies such as Oblivion (2013), Moon (2009), or even The 6th Day (2000).

Taylor is insteading using cloning as a metaphor for how culture can have a flattening effect when linked with the forces of capitalism. The film makes a powerful statement about how systemic inequality is often interwoven with consumerism in impoverished areas, which is why the movie’s ubiquitous setting of the Glen could be Anywhere, U.S.A. It has long been noted that Black communities are at a much higher risk for being forced into this cycle, as they often exist in “food deserts” where adequate grocery stores and other shopping options are unavailable; this explains why the characters in this movie feel like they’re living in a loop. When the audience discovers that the main antagonist of the film is the original version of the cloned protagonist, whose goal is to keep Black communities subjugated until they can fully assimilate into white culture, Taylor is directly lampooning the rhetoric of Booker T. Washington and other assimilationists. Get Out and Sorry to Bother You have similar moments in the climax of the films, as the message of each movie shifts from being tongue-in-cheek into a direct statement to the viewer about the horrors/dangers of systemic racism for Black people; however, the endings of all three movies provide very different lenses on this issue and are worth exploring further.

Get Out was a breakthrough film for Peele, though the ending was toned down for its wider release. In the original, when the hero escapes after his traumatic ordeal with the sinister white liberals, he hears a siren and a police car arrives on the scene; the police arrest him and he is charged with murder, mirroring the unfairness of the American justice system for Black people. Peele pulled back from this ending, however, as he said it made the audience “feel like we punched everybody in the gut” (Ronquillo)—this fictional situation was too horrible for the character to face after everything he had endured, despite it mirroring the reality of Black people in the real world. Peele’s choice to go with the “happy” ending would prove to be the commercially correct one, as it resonated with audiences and secured his Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. This is interesting, as it could be argued that the choice to turn into optimism is actually a pro-assimilationist stance that bows to the pressures of the moviegoing market (or to Hollywood), and this decision may have influenced Peele to critique the film industry (at least in California) in his most recent movie, Nope (2022).

In contrast, Sorry to Bother You is much more focused on how capitalism, rather than class, intersects with race, as the climax involves a completely bonkers sequence of events where the audience discovers that a diabolical CEO is using a cocaine-like substance to transform Black people into half-human horse hybrids. In one of the most genuinely shocking scenes I’ve seen in a long time, the movie shifts from absurd realism to outlandish science fiction as the hero stumbles across a number of “Equisapiens” locked away in the company’s back rooms. The last scenes of the film involve the horse people escaping and storming the CEO’s mansion, and They Cloned Tyrone takes a similar route for its conclusion: the “rising up” solution goes back to communities using protests and social unrest as the only way of changing unfair capitalist or racist structures. In They Cloned Tyrone’s final scenes, we find out that a clone is watching a version of himself escape from the government’s underground bunker on a news broadcast, and I feel this is a more thought-provoking ending than the other films because it doesn’t negotiate with capitalist forces or state that overthrowing them is the simple solution.

Instead, it asks an important question: How do our choices as consumers reinforce cultural and ethnic stereotypes, and in what ways are we all just copy/pasted versions of ourselves, consumer cogs grinding away in the American capitalism machine?

REFERENCES

Bakare, Lanre. “From Beyoncé to Sorry to Bother You: the new age of Afro-surrealism.” The Guardian. Dec. 6, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2018/dec/06/afro-surrealism-black-artists-racist-society.

Haile, Heaven. “They Cloned Tyrone Director Jule Taylor on His Favorite Conspiracies and Winning Over Erykah Badu.” GQ. Aug. 28, 2023. https://www.gq.com/story/they-cloned-tyrone-juel-taylor-erykah-badu-interview.

Moore, Lashaunta. “‘They Cloned Tyrone’ Was a Masterclass On Social Issues, But I Bet These 19 Things Went Over Your Head.” Buzzfeed.com. Aug. 1, 2023. https://www.buzzfeed.com/lashauntamoore/19-things-that-went-over-your-head-in-they-cloned-tyrone.

Jess Flarity teaches English and other classes at the Lake Washington Institute of Technology and Renton Technical college. He has a PhD in Literature from the University of New Hampshire and an MFA from Stonecoast.