Fiction Reviews

Review of The Kaiju Preservation Society

Kristine Larsen

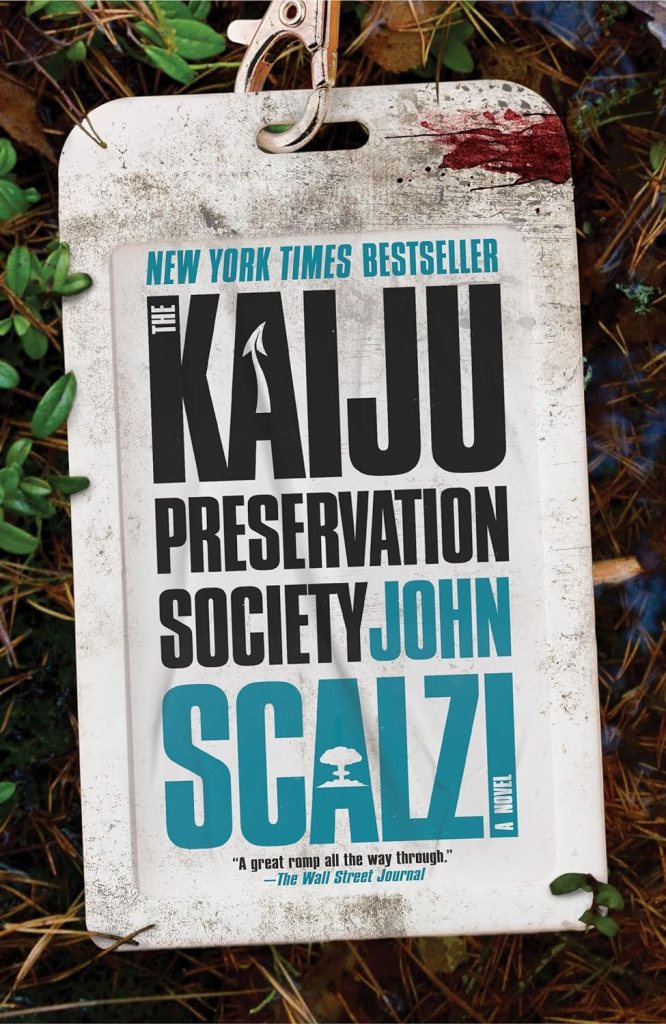

Scalzi, John. The Kaiju Preservation Society TOR, 2022.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Hugo Award winner John Scalzi struggled to complete a rather serious novel project before the contracted deadline, but eventually admitted defeat. He, like many of us, embraced the need for self-care, and instead produced what he calls in his lengthy Author’s Note a “pop song” of a novel, “meant to be light and catchy,” in less than six weeks (262). As he further explains, writing The Kaiju Preservation Society “was restorative…. I had fun writing this, and I needed to have fun writing this. We all need a pop song from time to time, particularly after a stretch of darkness” (262). However, just as a light-hearted earworm can garner Grammys, Scalzi’s replacement assignment was honored with the 2023 Alex Award of the Young Adult Library Services Association and the 2023 Locus Science Fiction Foundation Award for science fiction novel.

In the early months of COVID, first-person narrator and English Ph.D. program drop-out Jamie Gray finds that their six-month term at the management side of a start-up food delivery service does not go as planned. Reduced to delivering food for said company to make ends meet, Jamie meets a past acquaintance who offers employment at a mysterious company known only by the abbreviation KPS. The job is described as working with “large animals” in an isolated location for months at a time. After signing various ominous non-disclosure agreements, Jamie and several likewise underemployed Ph.D.s step through a nuclear-powered dimensional doorway in Greenland into a parallel Earth. But instead of a commercial ‘Kaiju Park’ featuring genetically engineered monsters, this is a natural ecosystem—albeit one featuring a completely alien biology—that scientists study while simultaneously preventing the kaiju from entering our world.

As Jamie and the reader discover, nuclear reactions “thin the barrier between universes” (41), allowing travel between these two Earths. The start of humanity’s nuclear age allowed several kaiju—who are themselves largely powered by their own internal nuclear reactors—to enter into our world in the 1950s. Although instinctively attracted to a new source of food—the fallout from nuclear bomb tests—the kaiju were ill-adapted to our world and quickly succumbed, although rumors of eyewitness accounts became the impetus for the original Godzilla film. An international project, KPS, was created to keep the kaiju on their side of the barrier while studying them in secret. Once funded by governments, billionaires now provide much of the support, leading to the inevitable: celebrity tourism. While the official gateways are tightly controlled by international agreement, the threat from unrestricted black-market doorways looms large; therefore, KPS also protects the kaiju from humanity, for as in the case of much of science fiction, the real monsters often wear a human face.

After surviving a number of threats posed by the wild kaiju and their parasites (bringing to mind a slightly kinder and gentler Cloverfield), Jamie and the scientists are drawn into a predictable conspiracy involving evil capitalists and the disappearance of a kaiju named Bella and her eggs during a conveniently scheduled shutdown of the official gateways. The rescue mission to return the kaiju and its young to their native climate (before Bella’s bioreactor becomes unstable and causes a nuclear disaster in our world) includes numerous mad scientist tropes, befitting the general timbre of the novel.

While the physical gateway between worlds is rather underwhelming (compared to passing through garage doors on opposite sides of a room), Scalzi does due diligence in world-building and scientific speculation for a novel of this relatively short length, especially on the biological side. As explained in an interview, Scalzi felt the need to provide a reasonable scientific basis for his giant creatures, explaining “God knows I love a Godzilla movie, but the physics of Godzilla are all wrong” (Sorg). The resulting fictional lifecycle of the kaiju is interesting; as a kaiju’s internal bioreactor can go critical, nuclear explosions are a natural part of the alien ecosystem. The resulting energy attracts other animals to feed upon the ‘carcass,’ providing a consistent explanation as to why the first hydrogen bomb tests attracted kaiju through the weakened dimensional wall into our world. The use of artificially developed kaiju pheromones to control kaiju behavior (including encouraging Bella and her reluctant mate Edward, members of an apparently endangered species, to breed) reminds one of a throwaway line involving T-Rex urine in Jurassic Park 3 (during a scene in which a young boy uses the liquid to scare away most of the island’s dinosaurs). Although some critics have poked holes in his science (e.g., Howe), the kaiju origin story is plausible enough for light science fiction. Indeed, this “pop song” of a novel certainly doesn’t take itself too seriously, delighting in numerous pop culture references to such disparate works as Stranger Things, Pacific Rim, Doom, Twilight, The Incredibles, and even Pitch Perfect for good measure.There are the expected direct nods to Japanese kaiju films, such as the names of the KPS bases playing homage to the original Godzilla’s director and producer. Subtle celebrity tourist name dropping includes the COVID-era president’s adult sons and possibly Bad Astronomer blogger Phil Plait.

Yet, for all these details there is scant description of the physical details of the individual kaiju (except for size), Jamie offering that human terms such as eyes and tentacles are insufficient to capture the unearthly physiology. Additionally, similar to protagonist Chris Shane of Scalzi’s Lock In (2014) and Head On (2018), Jamie Gray’s gender is never revealed. Scalzi openly embraces this (as well as the inclusion of trans or non-binary characters in the novel), offering that it is “reflecting the world I know” as well as the context of the communities described in the novel (Scalzi, “A Month”). Scalzi is also quick to warn in the same blog post that although Wil Wheaton reads the audiobook, this is not a clue to Jamie’s gender. Given that The Kaiju Preservation Society will probably be coming to a screen (small or large) near you before long, Jamie’s casting may provide an opportunity for a non-binary actor.

Reflecting on each reader’s individual gendering of his protagonist, Scalzi offers that “what they decide brings an interesting and personal spin to the book, and I like that. It’s also fun for people to interrogate their own defaults and what they mean for them as a reader and human” (Scalzi, “A Month”). Such interdisciplinary opportunities for open discussion, as well as the novel’s short length, eminent readability, and embrace of pop culture references, make it a natural for inclusion in the classroom, especially in a first-year experience course. The overall depiction of a pointedly diverse group of young Ph.D.s specializing in biology, astronomy/physics, and organic chemistry/geology—self-described as “the foreign legion for nerds” (32)—as heroes brings to mind not so much Jurassic Park but the John Carpenter film Prince of Darkness (without the cringy, red flag sexual relationships) and could spark useful discussions on depictions of science and scientists in popular culture. While Jamie is not a scientist, their master’s thesis on sci fi depictions of bioengineering is deemed appropriate preparation for the team. The group’s acceptance of Jamie as an equal—despite the lack of a Ph.D. and a background in the humanities rather than the sciences—is refreshing, reflecting current efforts to incorporate the arts into STEM education (the so-called STEAM movement). The ensemble nature of this ‘fellowship’ of the kaiju also reflects the process of science in an excitingly realistic way. The world is saved not by a lone genius, but a group of amusingly ordinary scientists, who tell bad jokes and delight in scatological humor. Although they utterly fail at being cool superheroes, through friendship and a convenient character twist good triumphs over evil. The setting of the novel during the COVID pandemic also encourages discussion of individual experiences during that time, reflecting how we, like the characters in the novel, were largely isolated from society, with the exception of our nearest family or friends.

While The Kaiju Preservation Society takes its reader on a relatively satisfying joy ride befitting a summer pop song, it will be interesting to see how it, like the musical ditty, holds up in five years, as we move farther away from the pandemic and our memories of the experience fade.

WORKS CITED

Howe, Alex R. “Book review: The Kaiju Preservation Society by John Scalzi.” Science Meets Fiction, 10 Sept. 2022, sciencemeetsfiction.com/2022/09/10/book-review-the-kaiju-preservation-society-by-john-scalzi/.

Scalzi, John. “A Month of The Kaiju Preservation Society.” Whatever, 19 Apr. 2022, whatever.scalzi.com/2022/04/19/a-month-of-the-kaiju-preservation-society/.

Sorg, Arley. “Friendship In the Time of Kaiju: A Conversation with John Scalzi.” Clarkesworld Science Fiction & Fantasy Magazine, Mar. 2022, clarkesworldmagazine.com/scalzi_interview_2022/.http://clarkesworldmagazine.com/scalzi_interview_2022/

Kristine Larsen, Ph.D., has been an astronomy professor at Central Connecticut State University since 1989. Her teaching and research focus on the intersections between science and society, including sexism and science; science and popular culture (especially science in the works of J.R.R. Tolkien); and the history of science. She is the author of the books Stephen Hawking: A Biography, Cosmology 101, The Women Who Popularized Geology in the 19th Century, Particle Panic!, and Science, Technology and Magic in The Witcher: A Medievalist Spin on Modern Monsters.