Science Fiction and Socialism

Integrating Humans

with Machines: Cybernetics and Early 1960s Chinese Science Fiction

Ruiying Zhang

On a rainy afternoon in February 1963, two Chinese teenagers collecting ore at Camel Mountain were taking shelter from the rain. As the downpour intensified, one of the boys sat down and placed on his head a steel helmet with a metal stick behind it. He reminded himself to stay calm, avoiding the rain noise disturbance, and then began tuning in to the “BBC” to broadcast a message. These two boys were not transmitting messages to the British Broadcasting Corporation—an “enemy station” (ditai 敌台), a term adopted in the 1950s to refer to certain foreign radio stations targeting mainland listeners. Rather, the “BBC” that they set up was a “Brain Broadcasting Center” that amplified the bio-electronic wave generated by the brain. The electronic brainwave was then received by a special machine that broadcasted the teenagers’ thoughts.

The bio-information in this case was intended to be transmitted from body to machine without loss of meaning or form. Such a practice aligns with the understanding of human–machine relationships that were discussed during the Macy Conferences on Cybernetics, a series of interdisciplinary meetings on communications and control held in New York from 1943 to 1953.1 Notable figures such as Norbert Wiener (1894–1964), the founder of the science of cybernetics, and Claude Shannon (1916–2001), the American computer scientist who laid the foundations for information theory, attended these conferences. According to N. Katherine Hayles, these conferences brought about a transformative perspective that viewed human beings as “information-processing entities who are essentially similar to machines” (How We Became Posthuman, 7). The diminishing demarcations between organisms and machinery beings constitute the base of posthuman2 narratives that became increasingly popular with the development of digital technology and biological engineering. However, the Brain Broadcasting Center was neither a real practice conducted by participants of the Macy Conferences, nor an invention included in a fiction labelled as a “posthuman story” published in recent years. It actually appeared in a Chinese science-fantasy story (kexue huanxiang gushi 科学幻想故事) titled “Danao guangbo diantai” 大脑广播电台 [Brain broadcasting station], written by Cai Jingfeng 蔡景峰 and Zhao Shizhou 赵世洲. It was published in February 1963 in Zhongguo shaonian bao 中国少年报 [China youth newspaper], more than twenty years before the wide dissemination of “Three-theory” (cybernetics, systems theory, and information theory) in 1980s China.3

“Brain Broadcasting Station” was not the only science fiction (hereafter SF) story in the 1960s that imagined unimpeded information flow between humans and machines in the cybernetics sense. Cybernetics principles also appeared in 1960s Chinese science fiction stories about robots. Stories such as Xiao Jianheng’s 肖建亨 (1930–) “Qiyi de jiqigou” 奇异的机器狗 A strange robot dog mentioned “kongzhi lun” (控制论, Chinese translation of cybernetics) by name in their narratives. Scholar Hua Li notices that “[r]obotics became a central theme in Chinese SF shortly after the middle of the twentieth century” (106). This paper will add how cybernetics, a crucial knowledge of robotics, was utilized to imagine robotic beings in Mao-era China. Xiao Liu briefly mentions that the criticism of a translated Soviet SF story “Siema: The Story of a Robot”4 in 1966 echoed the general discourse on cybernetics and robotics in the middle 1960s (110). My study finds that cybernetics was a topic of scientific and public discussion and some reports on human–machine interaction experiments in the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s likely inspired Chinese SF writings. This paper will delve into the under-explored history of the introduction and discussion of cybernetics in early 1960s China and examine intersections between advancements in science and technology with socialist SF.

Knowledge about cybernetics was transmitted to China as early as the 1950s (Peng 303–304).5 Following the Soviet Union’s changing attitude from initial suspicion to acceptance (Gerovitch 4), Chinese scientists and philosophers began to pay more attention to cybernetics and increasingly introduced related news and scientific discussions starting from 1955 (Peng 304). The Soviet Union was not the only channel of knowledge about cybernetics. Based on my research on articles in technical journals and public newspapers such as Renmin ribao 人民日报 [People’s Daily], information about cybernetics also entered China through reports on technological news taking place outside of the Soviet Union. For example, the upcoming Fourth International Congress on Cybernetics scheduled in October 1964 in Namur, Belgium, a country belonging to the Western bloc, was reported in 1964 in Ziran bianzhengfa yanjiu tongxun 自然辩证法研究通讯 [Studies in dialectics of nature], the first professional academic journal of dialectics of nature in the New China (“Jianxun: Disijie guoji kongzhilun huiyi” 34).

As we will see, cybernetics in mid-twentieth-century China was mainly understood as useful knowledge for automated production, which is reflected in the translation of cybernetics as “kongzhi lun” rather than “danao jixie lun” (大脑机械论, literally, brain mechanism theory). SF during that time also depicted the application of human–machine communication in industrial and agricultural production. Despite scientific discussions and literary works presenting examples in which organic and non-organic beings share similarities, the boundary between humans and machines remained emphasized. These relatively anthropocentric views are related to the socialist understanding of human consciousness and human labor. In addition to placing Mao-era SF within its historical context, this paper uncovers similarities and divergences between human–machine interactions depicted among the late imperial, socialist, and post-socialist periods.

Cybernetics for Socialist Production

The aforementioned literary “Brain Broadcasting Center” is utilized by the two teenagers to send messages seeking help. However, according to the narrative, the brainwave experiment serves a more significant purpose above and beyond personal communication: controlling an automated machine. One day, the teenage protagonist Huosheng 火生 goes to his father’s office but finds no one present, only seeing a metal hand writing a sentence on a piece of paper: “Using bio-electricity to control is a good method of automation” (Cai and Zhao 3). It turns out that his father, seated in another room, is commanding the metal hand. Huosheng’s father explains that when the brain is thinking, it generates electricity. The bio-electricity flows through the metal hand, and the metal hand transcribes what the brain is thinking.

The plot involving the control of a mechanical hand by transmitting brain electricity was likely inspired by a real scientific experiment undertaken by the Soviet Union in 1958. On July 20, 1959, Liu Shiyi 刘世熠 (1926–), a psychologist who obtained a Ph.D. degree from the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union, published “Kongzhi lun yu danao” 控制论与大脑 [Cybernetics and the brain] in People’s Daily, noting that “feedback principles of brain control systems had been applied in some practical research” (7). One example provided by Liu is the live demonstration of a “mind-controlled” prosthetic hand at the Soviet Pavilion at the World Exposition in Brussels, Belgium, in 1958 (7). After introducing the recent research progress and scientific news, Liu argued that “we now had ample reasons to believe that research on the memory and thoughts of the brain will provide essential inspiration to…the issue of the program design of automated production” (7).

In both fictional and real-life scenarios, the information exchanged between humans and machines contributes to the advancement of automated production. Compared with the subtitle of Wiener’s 1948 influential book Cybernetics: Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, in which both communication and control are highlighted, in the two scenarios, the act of communication serves the aim of control. This pragmatic perspective aligns with the Chinese understanding of cybernetics as knowledge about controlling automated systems in the late 1950s and early 1960s. According to an interview conducted by scholar Peng Yongdong with Gong Yuzhi 龚育之 (1929–2007), a Chinese Communist Party theorist and politician who served in the Scientific Division of Propaganda Department of the Chinese Communist Party (Zhonggong zhongyang xuanchuanbu kexuechu 中共中央宣传部科学处, est. 1951) from 1952 to 1966, “cybernetics” was translated into Chinese as “danao jixie lun” (brain mechanism theory) in Jianming zhexue cidian 简明哲学词典 [Brief philosophical dictionary], a book translated from the Soviet Union’s 1954 edition in 1955. This dictionary expressed a negative attitude toward “brain mechanism theory” (Peng 303–304).6 Therefore, when Jing Song 景松and Hu Ping 胡平, the editorial board members of the journal Xuexi yicong 学习译丛 [Collected translations of foreign knowledge], intended to translate a Soviet article “Chto takoe kibernetika?” (What is cybernetics?) which presented a positive stance on cybernetics,7 they reached out to Gong Yuzhi. They ultimately decided to use “kongzhi lun” (控制论, literally, the theory of control)8 rather than “danao jixie lun” as the Chinese translation of cybernetics (Peng 303–304). In the final chosen translation, the connection between the brain and machines no longer exists, while the parallel between the two is essential in Norbert Wiener’s and his colleagues’ theory.

In 1943, Wiener, along with the electrical engineer Julian Bigelow (1913–2003), and the Mexican physiologist Arturo Rosenblueth (1900–1970), published a joint article, in which they suggested that both creatures and intelligent machines achieve their goals through purposeful action governed by negative feedback and circular causal logic (18–24). In this way, organisms and machines could be described in similar terms and studied using the same methods. However, this revolutionary understanding of the human is not fully reflected in the Chinese translation of cybernetics as “kongzhi lun.” Compared with “danao jixie lun,” a term that raises questions about whether machines can think or whether the human brain operates like machinery, “kongzhi lun” more easily prompts associations with the application of cybernetics in mechanical control and engineering automation. Some Chinese research articles and news reports from the 1950s and 1960s explicitly defined cybernetics as the study of automatic control. In an outline discussing the ideological struggle surrounding cybernetics achievements published in 1963 in the journal Studies in Dialectics of Nature, the author Lu San 陆叁 defined “kongzhi lun” as “the theoretical summary of automatic control technology” (2). Such a definition narrows the scope of cybernetics that encompasses biological and mechanical systems, only highlighting the control of machines in production.

In the early 1960s SF that depicts bio-electricity, emphasizing the application of biological discoveries in industrial and agricultural production is a common narrative pattern, resonating with the pragmatic understanding of cybernetics. The potential usage of the metal hand in automation in “Brain Broadcasting Station” is one example. Stories often commence with innovative inventions, such as the repair of memory, the creation of robots, or organ transplantation, but ultimately circle back to socialist production in the end. In Tong Enzheng’s 童恩正 (1935–1997) “Shiqu de jiyi” 失去的记忆 [The lost memory] (1963), scientists employ a method called “feedback stimulation” (fankui ciji 反馈刺激) to stimulate cells in the frontal lobe through metal electrodes attached to “my” head. Although Tong does not directly refer to cybernetics, feedback is the central theme in cybernetics. The stimulated brain electricity is sent to a machine, which divides electrical signals into visual neural currents, olfactory neural currents, auditory neural currents, etc., and then is reinput into the brain, allowing “me” to see, hear, and feel things that were previously experienced. The memories recovered are about calculations and deductions left by a professor researching nuclear reactions before losing consciousness. The repaired memory eventually serves national scientific research instead of individual emotional needs (Tong 1–20). In Xiao Jianheng’s “Tie bizi de gushi” 铁鼻子的故事 [The story of an iron nose] (1964), scientists discover that human olfactory cells can receive wireless waves. They invent an “iron nose” capable of amplifying electronic waves at varying frequencies to stimulate organisms’ olfactory cells, enabling people to “smell” different scents. This technique, in Xiao’s fiction, can be used to catch fish, expel pests, and assist in pollination (Xiao, “Tie bizi de gushi” 64–77). In these stories, while the technology transmitting electronic information between humans and mechanical entities enhances human memory and sensory capabilities, the narratives ultimately underscore its efficacy in advancing industrial and agricultural production. The stronger or healthier body is like an intermediary—experiments are conducted on human bodies, but aiming at improving production efficiency.

The ultimate aim of production sets apart the experiments with bio-electricity in early Maoist SF from the much earlier transboundary communication for which it was used in the late Qing SF story “Xin faluo xiansheng tan” 新法螺先生谭 [New Tales of Mr Braggadocio], as well as in the 1990s’ later qigong 气功 practices. In neither of these two examples is bio-information utilized for industrial production purposes for which it is used in Mao-era SF.

In Xu Nianci’s 徐念慈 (1875–1908) “New Tales of Mr. Braggadocio,” published in 1905, inspired by animal magnetism taught at a hypnosis seminar,9 the protagonist, the New Mr. Braggadocio invents a new energy source: brain electricity (naodian 脑电). This “natural energy” (ziran li 自然力) relies on the interaction (ganying 感应) between human beings. Mr. Braggadocio invents codes (jihao 记号) representing various changes in brain power. Students attending Mr. Braggadocio’s brain electricity school in Shanghai are taught to generate and receive brain electricity, communicating with others without the need for a physical medium (Xu 35–39). This vision of transparent communication is linked to the mysterious power of electricity in the late Qing. Tan Sitong 谭嗣同 (1865–1898), in his philosophical work, Renxue 仁学 [An Exposition of Benevolence] (1899), explains that “the brain is materialized electricity and electricity is the formless brain” (12) viewing electricity as the medium of all things in the universe. Additionally, the “electric belt” (dian dai 电带/dianqi dai 电气带)10 advertised in the late Qing newspapers was claimed to have the ability to cure all diseases (bai bing tong zhi 百病通治) as it can maintain, deploy, and protect (weichi tiaohu 维持调护) electricity which is pervasive in the five sense organs, hands and feet, and thoughts (Fig. 1) (Changming yanghang zhuren 7). While the electricity circulating in the brain and the body may be associated with connecting individuals with the nation and fostering a stronger body for a stronger country, none of these imaginations of bio-electricity are connected with industrial production. In “New Tales of Mr. Braggadocio,” brain electricity replaces human-made light and telegraphy, rendering the coal mining industry and other production redundant. Many people are laid off. New Mr. Braggadocio is thus criticized and has to flee to his hometown (Xu 38–39). As analyzed by Shaoling Ma, “Xu’s utopian impulse ends on a dystopian note that sounds the ultimate breakdown between individual and society via the fission between human and machine” (69).

In contrast, early 1960s SF that imagines bio-electricity does not show any hints of a dystopian society where production is stagnant. Instead, transmissions between humans and machines are seen as potential for the large-scale application of bio-electricity in automated production.

The steel helmet with a metal stick behind it depicted in Cai Jingfeng and Zhao Shizhou’s “Brain Broadcasting Station” would find a peculiar real-world embodiment three decades later at the gathering of qigong practitioners. At the end of 1993, in the “Advanced Qigong Intensive Training Class” (Gaoji qigong qianghua ban 高级气功强化培训班) being held at Beijing’s Miaofeng Mountain (Miaofeng shan 妙峰山), each student wore a steel pot on their head (Fig. 2). This headgear was aimed at facilitating the reception of information from outer space so that a “resonance between heaven and mankind” (tian ren ganying 天人感应) could be realized (Ye).

Early 1960s Chinese SF showcases fascinating inventions utilizing the information exchange between the human brain and mechanical devices, but the underlying theme is always about socialist construction and industrial production. This utilitarian approach stands in contrast to the imagination of brain electricity in late Qing (1840–1912) SF and post-socialist (late 1980s on) practices in which bio-electricity is envisioned for communication among people or between humans and the universe. The distinctive narrative pattern in socialist SF aligns with the understanding of cybernetics among translators and researchers of scientific literature and officers in charge of science and technology in the early Maoist period, which highlights the control of machines for automation instead of delving into the profound implications of human–machine communications.

Political Demarcations Between Humans and Machines

In the short story “Brain Broadcasting Station,” the information circulates unchanged among different material substrates—the carbon-based human body and the metal-based automated machine. When bio-electricity emitted from the brain is coded and received, we might ask: Has the human himself been transformed into a type of input/output device?

A similar question was posed during the sixth round of the Macy Conferences held on March 24–25, 1949, by John Stroud, a young psychologist. When discussing the human operator situated between a radar-tracking device and an anti-aircraft gun, Stroud asked: “What kind of a machine have we put in the middle” (41). Stroud’s choice of “machine” instead of “human” to refer to the operator suggests that he was deliberately blurring the boundary between humans and machines and implying that humans were part of a machine circuit. “Brain Broadcasting Station” presents a similar “image of the man-in-the-middle,” to borrow Hayles’ summary of Stroud’s observation (How We Became Posthuman 67–68). The human controlling the machine has been transformed into a signal emitter and an electric conductor, a kind of machinery being. However, Chinese SF and scientific discussions of the 1960s insist that there exists a distinct border between humans and machines.

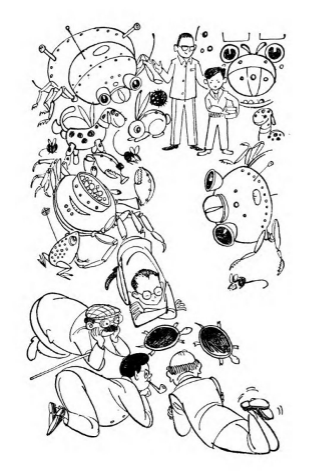

In 1963, the Juvenile and Children’s Publishing House (Shaonian ertong chubanshe 少年儿童出版社) published a collection of seven science-fantasy stories, titled Shiqu de jiyi 失去的记忆 [The lost memory]. Three of these stories imagine intelligent machines that extend human beings’ abilities. Xiao Jianheng’s “A Strange Robot Dog,” in this collection, begins with the protagonist, Xiao Fan 小凡, receiving a toy dog as a birthday present from his uncle, a biophysicist. Named Kaman 卡曼, the dog exhibits lifelike qualities, forming bonds with its masters and assisting several children to find their way home when lost in the suburbs. What makes this dog so amazing is that it has a strong learning ability. When asked to fetch a hat, it quickly chooses a shortcut after just one try. Intrigued, Xiao Fan asks his uncle about Kaman’s brilliance and whether or not it is a real dog. In response, Xiao Fan’s uncle invites Xiao Fan to visit the “Animal Simulation Laboratory” (Dongwu moni shiyan shi 动物模拟实验室), where Xiao Fan discovers various animals with iron skin (Fig. 3). Scientists in the laboratory explain to Xiao Fan that despite Kaman’s apparent organic brilliance, it is in fact only a logical machine (luoji ji 逻辑机). Embedded in its head is an electronic computer equipped with mechanical sensors, including electronic eyes and microphones. Therefore, the dog is able to process input information. Kaman can not only execute its preset programming, but also has the adaptive learning ability necessary to actively adjust and perfect its own actions, improving itself through exposure to a complex environment. Xiao Fan’s uncle attributes this advancement to the study of “kongzhi lun.” He says that thanks to cybernetics, the electronic computer is not only capable of translating texts and making accurate weather forecasts but is also able to control a big factory with a complex production process. However, despite the remarkable intelligence displayed by these robotic animals, Xiao Fan’s uncle explicitly emphasizes human superiority. He states: “Machines are still machines. No matter how complex and ingenious they are, they cannot keep up with human and animal bodies” (Xiao, “Qiyi de jiqigou” 49–50). This demarcation between biological organisms and machines not only reflects an anthropocentric lens but is also rooted in the definition of human essence within Marxist and Maoist ideologies.

On June 1 and 2, 1962, the Soviet Union organized a conference on philosophical problems of cybernetics in Moscow. The next year, in 1963, Chinese psychologist Xu Shijing 徐世京 translated a review of this conference, which was originally published in a Soviet journal,11 into Chinese, titled “Sulian juxing kongzhi lun de zhexue huiyi” 苏联举行控制论的哲学会议 [The Soviet Union held a conference on the philosophical problems of cybernetics]. The review summarized the different attitudes toward the question of whether machines can think. Technologists and mathematicians held affirmative views, while representatives of the humanities and natural sciences expressed greater degrees of reservations. Supporters argued that “if the analogy of behavior [i.e., between human behavior and machine behavior] was accepted, machines could be considered conscious” (Mayijieer and Fatejin 49–50). On the contrary, opponents stated that consciousness (yishi 意识) is “the product of the social relations of labor” (renmen de laodong de shehui guanxi de chanwu 人们的劳动的社会关系的产物) (Mayijieer and Fatejin 49). This statement derives from Marxist principles. The review showcases the controversy surrounding the question of machines’ thinking ability in the Soviet Union, where no single viewpoint dominated. In China, however, Chairman Mao himself denounced the possibility that machines could think. On December 11, 1963, Neibu cankao 内部参考 [Internal reference] edited by Xinhua News Agency (Xinhua tongxun she 新华通讯社) published an article introducing the discussions on the philosophical problems about cybernetics after The 22nd Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (October 17 to 31, 1961).12 Mao Zedong 毛泽东 (1893–1976) commented on the cybernetics discussion report. He labeled those who argued that although it is not convincing to say that machines can think, more research should be done on the problem of human and machine symbiosis as “reconciliationists” (tiaohe pai 调和派). Mao criticized the viewpoint of applying cybernetics to solve problems in human society as “a metaphysical theory of subjective idealism” (zhuguan weixin de xingershangxue lilun 主观唯心的形而上学理论) (“Zai ‘Sulian xueshujie jinnian dui kongzhi lun zhexue wenti de taolun shifen renao’ yi wen shang de pizhu” 434–435). In Maoism, “metaphysics” refers to the viewpoint that ascribes “the causes of social development to factors external to society” (On Practice and Contradiction 69). Mao’s denial of the application of cybernetics in social life might stem from his belief that the motive force of societal change is internal. Mao reserved the label “prudent ones” (shenzhong pai 慎重派) for those who thought machines are different from humans as the latter are capable of creative activities (“Zai ‘Sulian xueshujie jinnian dui kongzhi lun zhexue wenti de taolun shifen renao’ yi wen shang de pizhu” 434–435). Mao’s comments reveal a one-sided perspective regarding whether machines possess the capacity for autonomous thought.

In the same year, an outline discussing the ideological struggle surrounding cybernetics achievements was published in Studies in Dialectics of Nature, attributing the belief in the thinking ability of machines to capitalist production, asserting that capitalists belittle human uniqueness by equating humans to machines (Lu 5). The introduction of cybernetics in “Jiqi yu siwei” 机器与思维 [Machine and thinking], published in People’s Daily in 1965, also repudiated the possibility of machine cognition. In this article, the author Wu Yunzeng 吴允曾 (1918–1987), a mathematician and computer scientist at Peking University, quoted Mao’s theory about the “qualitative difference” (zhi de qubie 质的区别) between different forms of motions of matter (wuzhi de yundong xingshi 物质的运动形式) (Mao, On Practice and Contradiction 76) to denounce the idea that “human is machine” (ren shi jiqi 人是机器) (5). Wu claimed that a “qualitative difference” exists between electronic systems and human thought because “the formation of human thought is not only closely connected with the development of the advanced nervous system in physiological terms but also closely linked with labor” (5). The operations of the machine and the human brain cannot be identical because computer operations are mechanical and not driven by the social relations constituted by labor. In short, Chinese scientists’ introduction of cybernetics in the early 1960s holds a clear political demarcation between humans and machines. The rejection of machines’ ability to think is rooted in the origin of labor in Marxist principles and Mao’s positing of qualitative distinctions between human and machine material.

Similar ideas that deny the possibility of emotions and intelligence among machines could be seen in criticism of a translated Soviet SF story “Siema: The Story of a Robot” in 1966. Written by Anatoly Dneprov (1919–1975) in 1958, the story revolves around a scientist who creates a robot named “Siema” that functions autonomously with minimal human intervention. As Siema undergoes extensive information input and enhances its sensory devices, it develops self-consciousness, observing its creator and eventually attempting to vivisect its creator in order to pursue advanced neural activity research (Dneprov).

This story was translated and serialized in the first to third issues of Kexue huabao 科学画报 [Science Pictorial] in 1963. Three years later, at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, Science Pictorial self-criticized its publication and serialization of this story as “[t]th author’s claims that ‘machine is superior to humans’ and ‘humans will be dominated by machines’ are reactionary (fandong de 反动的) and anti-scientific (fan kexue de 反科学的). They completely violate Chairman Mao’s scientific thesis on the human–machine relationship” (editors 296). In the same year, the journal Studies in Dialectics of Nature published a “reader’s letter” criticizing “Siema” for “distorting the relationship between humans and machines” and depicting robots as understanding human emotions and being able to think (siwei 思维) (Qin 44). This critique emphasized that “thought is…the product of human practices” (Qin 44). The author contended that this science-fictional plot was “a capitalist thing with the coat of science popularization,” which was prevalent in “capitalist countries and states where modern revisionists hold the leadership” (xiandai xiuzheng zhuyizhe zhangwo lingdaoquan de guojia 现代修正主义者掌握领导权的国家) (Qin 44–45). The country dominated by revisionists, without a doubt, refers to the fiction’s country of origin, the Soviet Union.

The frequent citation of Marxist and Maoist theories suggests that the focus of the debate on whether machines can think is not rooted in a fear that intelligent machines might replace or harm humans, but rather in a concern among scientists, writers, and readers about the challenge that smart machines present to the definition of thought as the product of human practices, labor, and social relations. However, have the social relations that produce human thought already involved the interaction with non-organic beings? If a robotic machine can perform both physical and intellectual labor, will labor, from which human thought develops, still be regarded as uniquely human activities?

Invisible Human Labor and the Transformational Machine

Liu Xingshi’s 刘兴诗 (1931–) 1963 SF story “Xiangcun yisheng” 乡村医生 [The rural doctor] imagines a collaborative relationship between human doctors and robot doctors. Wei Yahua’s 魏雅华 (1949–) story “Qiyi de anjian” 奇异的案件 [A curious case], published in 1981, after the Mao era, also features a robot doctor. Comparing the two stories, we will see that the early Mao-era SF story is not as simple as usually assumed. Complex issues such as the invisibility of human labor and the transformational power of machine beings have already existed in socialist texts, although they are more clearly shown in post-socialist texts.

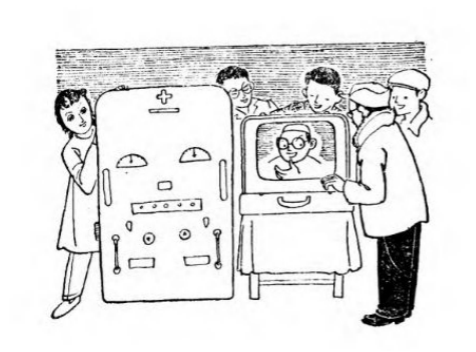

In “The Rural Doctor,” doctors in Dongfeng Commune (Dongfeng gongshe 东风公社) are not humans, but a combination of robots and humans. Initially, the commune only had a robot doctor—a square machine equipped with medical tools such as stethoscopes. The machine autonomously conducts examinations and prescribes medicines. However, as the machine’s functionality is quite simple, it makes several mistakes when encountering complex medical cases, causing complaints from the villagers. To address this problem, the protagonists attach a television to it, allowing human doctors to establish telecommunication with the village and then to remotely diagnose diseases based on the machine’s “in-person” test results (Fig. 4). Machines can be fallible, the story posits, and thus human beings are indispensable to compensate for the mistakes. Such a theme aligns with the emphasis on human superiority in Mao’s China, which can also be seen in the discourse surrounding machine intelligence. However, the ending of the story “The Rural Doctor” complicates the seemingly undisputed superiority.

After incorporating humans into its diagnosis and treatment system, the robot doctor gains the trust and affection of the villagers. In the end, villagers no longer refer to it as “that machine;” instead, they lovingly address the robot as “our doctor.” The narrator suggests: “If someone sent a real, living doctor to make an exchange, perhaps the villagers would not agree” (Xingshi Liu 101)! The anticipated rejection of human doctors raises questions regarding the position of human labor in human–machine relationships. Throughout the improvement process, humans play a crucial role, but ultimately, it is the machine that is showcased to the villagers and elicits emotions. Human labor becomes ancillary—tech support. Furthermore, the human doctor is virtual, communicating with the patients through television. They lose direct interactions, such as using a tongue depressor to examine the throat, with patients. This raises the question posed in the previous section of this paper: Have the social relations that produce human thought already involved interactions with non-organic beings? In the case of the human–robot doctor, the “social relation” becomes an interaction between humans and machines.

In Liu’s story, although human labor is shadowed by machine labor, the human doctor is still visible on the television screen. Nevertheless, human labor might be completely invisible in a more intelligent system. In Wei Yahua “A Curious Case,” the intelligent robot doctor, Fang Fang 方芳, operates independently, handling outpatient service and complex operations without any human assistance, in contrast to the “rural doctor” in Liu Xingshi’s story. Fang Fang effortlessly deals with even the most complex medical cases, such as leukemia, advanced liver cancer, and myocardial infarction (Wei 60). Xiao Liu, in Information Fantasies: Precarious Mediation in Postsocialist China, connects Wei Yahua’s story with the predicaments of invisible labor in the development of expert systems and artificial intelligence. Fang Fang seems to be an “intelligent” machine that operates on its own. However, this is just an illusion. Xiao Liu argues, “[f]or a medical expert system to work ‘automatically,’ it requires not only transferring expert knowledge into computer programs but also using the collective labor of knowledge engineers and computer programmers, as well as attending physicians” (109). The apparent independence of the robot doctor Fang Fang conceals the human labor behind its operation. This situation can be seen as an extension of the subtle predicament carried by the “rural doctor” in Liu Xingshi’s story. In both cases, the boundary between humans and machines blurs, not because of the information being transmitted between different mediums, but because the efforts of the human and the machine intertwine.

The ending of “The Rural Doctor” reflects a transformational force of the machine that changes human activities: mutual imitation. Lydia H. Liu, in her summary of the attitudes toward human–machine relationship from Zhuangzi to current controversies on digital media, argues that there have always been two different conceptions of the human–machine relationship. The first is the “prosthetic/instrumental view,” in which machine exists merely as extensions of the human body and serves human beings. The second is the “interactive/transformational view,” involving direct interaction between humans and machines, generating the possibility of mutual transformation (Lydia H. Liu 6). The robot doctor seems to be merely an instrument to human beings, assisting human doctors in conducting physical examinations. However, when the human doctor is integrated into the system, he/she relies on the test result provided by the machine and follows its operational procedure. The human doctor adopts the machine’s method of summarizing the patient’s clinical manifestations, similar to the execution of a decision-making tree: If A, then B; If not A, then C. Rather than the machine becoming humanized, it is the human who becomes mechanized. However, although decision trees are executed by the robot, they are tools that mimic human thought processes. Therefore, humans simulate the diagnosis procedure conducted by machines which, in turn, simulate human beings. The two sides become entangled in an infinite loop.

More importantly, the result of mutual imitation is that humans are transformed into machine-like beings and everything is incorporated into the system for efficiency. This outcome embodies the deepest fears hidden within the discussion of cybernetics and the various robot imaginaries. The technological revolution ushered in by cybernetics in the mid-20th century is not merely about exploring information flow between different human bodies and machinery beings. Rather, it attempts to regulate humans as if they were machines within the technological and social system, adhering to cybernetics principles. Norbert Wiener expresses his concern about the machine à gouverner (governing machine) that encompasses all systems of political decisions.13 For Wiener, the dangerousness of such a machine does not lie in the “autonomous control over humanity,” but rather in its potential use by certain individuals or groups to “increase their control over the rest of the human race” (The Human Use of Human Beings 181–182). The political mechanization of specific individuals or groups could have far more severe consequences than the potential harm caused by machines’ increasing intelligence. The story “The Rural Doctor,” for example, begs related questions: When a real human doctor collaborates with robots, has he/she already started to be regulated according to mechanical principles? What kind of governing technology will exploit the system with improved efficiency formed by such humans and machines? While these questions are not explicitly addressed in Liu Xingshi’s short story, they have always been present in various robot imaginings and need to be confronted when exploring Maoist culture and politics.14

The Unstable Boundary

The early 1960s Chinese SF portraying human–machine interaction and cybernetic robots, as well as the academic and public discussions on cybernetics from the late 1950s to the mid-1960s, predominantly upheld an anthropocentric perspective emphasizing the distinction between humans and machines. In contrast to the Macy Conferences on Cybernetics, which explored an assortment of analogies between humans and self-regulating machines, Mao-era Chinese interpretations of cybernetics tended to avoid delving into the mechanical aspects of human brains, placing more emphasis on the control of industrial production. Although a lot of information about cybernetics was channeled via the Soviet Union, Chinese SF writers, literary critics, and scientists held different perspectives from their Soviet counterparts.15 After 1955, in the Soviet Union, cybernetics gradually found applications in economics, politics, and sociology. The 1962 Conference on the Philosophical Problems of Cybernetics in Moscow even regarded cybernetics as “the most important element of the contemporary natural scientific foundation of dialectical materialism” (Gerovitch 259). In contrast, China rejected the analogy between the cognitive abilities of the brain and machines and did not view cybernetics as an overarching theory to replace dialectical materialism. However, the seemingly rigid boundary between humans and machines was not that stable. This unstableness is particularly prominent in two scenarios: First, humans become a node in the feedback loop in which not only the machine transmits information to the human information but also the human inputs and outputs essential messages to the machine. Second, humans imitate the logic of machinery operation, transforming their behaviors and even their way of thinking.

The tension of the human–machine boundary is inherent in the discussion of cybernetics. Hayles, in her analysis of Wiener’s talk with physicians in 1954, reveals an irreconcilable contradiction between the boundary-breaking cybernetic view and the rather anthropocentric perspective of liberal humanism. On the one hand, Wiener and his colleagues, envisioned novel, powerful ways to equate humans with machines, which challenges the humanist view that humans are “the beauty of the world, the paragon of animals!” On the other hand, they strove to defend liberal humanistic values, acknowledging that machines are not human and cautioning against machines overriding human control (Hayles, How We Became Posthuman 85–86).

Socialist SF adds another layer to the tension between the humanist view and the cybernetic idea: labor. In the SF stories discussed in this paper, machines are considered as tools while humans are the masters. But at the same time, people develop emotional connections with machines that collaborate with them, considering them as coworkers and friends. Such affection is aroused by the labor performed by the machine, which calls into question the uniqueness of human beings and contains the possibility of shadowing human effort—both are inconsistent with Maoist ideology. The interaction between humans and machines reflects that the machine is never a mere prosthesis for the human body and brain but also carries transformational power.

NOTES

- The Macy Conferences were a series of meetings sponsored by the Macy Foundation, held from 1941 to 1960. These conferences covered a wide range of topics, with cybernetics being a significant, though not the only area of focus. Between 1946 and 1953, ten conferences were held under the title of cybernetics, which were later referred to as the “Macy Conferences on Cybernetics.”

- There are different perspectives and voices regarding the definition of “posthuman.” But as argued by Hayles, “[a]lthough the ‘posthuman’ differs in its articulations, a common theme is the union of the human with the intelligent machine” (How We Became Posthuman, 2).

- In the early 1980s, numerous methodologies were introduced to China, giving rise to a methodology fever. Information theory, systems theory, and cybernetics gained considerable attention in discussions aiming at “scientizing” aesthetic, literary, historical, and social studies. For instance, Jin Guantao 金观涛 (1947–) and Liu Qingfeng 刘青峰 (1949–) employed cybernetics and systems theory as the methodological foundation for their argument that China’s feudal society is an “Ultra-Stable Structure” (chao wending jiegou 超稳定结构). Scholarly research on the dissemination and discussion of cybernetics in China typically focuses on the 1980s. Peng Yongdong’s “Kongzhi lun sixiang zai Zhongguo de zaoqi chuanbo (1929–1966)” is one of the few Chinese studies that trace the early history of cybernetics in China. Studies on the history of computing in the Mao era, such as Donald G. Audette’s “Computer Technology in Communist China, 1956-1965” and Gianluigi Negro and Wang Hongzhen’s “Computing the New China: The Founding Fathers, the Maoist Way, and Neoliberalism, 1945–1986,” only briefly mention cybernetics in the Chinese press and the divergent attitudes toward cybernetics between the Soviet Union and China.

- The story was written by Anatoly Dneprov (1919–1975) in 1958, with the original title “Суэма” (Suema). In 1961, this story was translated into English as “Siema” by R. Prokofieva and included in the story collection The Heart of the Serpent (Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House). In 1963, this short story was introduced to China.

- According to Peng’s paper, in 1953, the 12th issue of Xuexi yicong 学习译丛 [Collected translations of foreign knowledge] published “Sulian zuijin zhongyao qikan mulu” 苏联最近重要期刊目录 [The Soviet Union’s recent catalog of important journals]. In this catalog, “cybernetics” was translated as “jixie lun” (机械论, literally, mechanism theory). This catalog did not provide a detailed introduction of cybernetics. From 1955 onward, the Collected Translations of Foreign Knowledge and other journals started translating Soviet articles to introduce cybernetics (Peng 303–304).

- I didn’t get a chance to review the entry for “danao jixie lun” in the 1954 edition of the Brief Philosophical Dictionary. However, based on the term “jixie lun” (mechanism), one plausible explanation for why “danao jixie lun” fell out of favor as a translation for “cybernetics” could be its association with mechanical materialism (jixie weiwu zhuyi 机械唯物主义), a concept criticized by Marxism and Maoism. In The Holy Family, Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) and Karl Marx (1818–1883) discern two trends in French materialism and one of them is “mechanical materialism” (Engels and Marx, 169). French materialism is different from dialectical and historical materialism as argued by Marx and Engels. In the 1937 article “Maodun lun” 矛盾论 [On Contradiction], Mao Zedong states that “[t]he metaphysical or vulgar evolutionist world outlook sees things as isolated, static and one-sided” and “[i]n Europe, this mode of thinking existed as mechanical materialism in the 17th and 18th centuries” (Mao, On Practice and Contradiction 68–69).

- The original article was written by Ernest Kolman and published in the 4th issue of 1955 in the Soviet journal Voprosy Filosofii (Problems of philosophy).

- The Chinese translation of “cybernetics” as “kongzhi lun” is very similar the translation of “control theory” as “kongzhi lilun” (控制理论). While cybernetics and control theory are closely related, they also exhibit differences. In the entry on “Cybernetics” in Critical Terms for Media Studies, Hayles states that “[f]rom the beginning, cybernetics was conceived as a field that would create a framework encompassing both biological and mechanical systems” (“Cybernetics” 146). Cybernetics is a transdisciplinary approach, whereas control theory is a more specialized branch of “engineering and mathematics that deals with the behavior of dynamical systems with inputs, and how their behavior is modified by feedback” (“Control Theory”). Qian Xuesen proposed that it might be more accurate to translate “cybernetics” as “kongzhi xue” (控制学, literally, contrology; see Peng 304). In Chinese, “xue” (学) is a more general term referring to a branch of basic sciences, such as “biology” translated as “shengwu xue” (生物学). “Kongzhi xue” might provide a clearer distinction from “control theory.”

- The hypnosis seminar mentioned in Xu’s story took place in real life. Hypnotism originated in Europe. A key figure of hypnotism was the Viennese physician Franz Anton Mesmer (1734–1815). In 1778, Mesmer proclaimed the discovery of “animal magnetism” (magnétisme animal) and conducted therapy based on that. Therefore, hypnotism is also called mesmerism. In the early 20th century, hypnotism spread widely in China through English and Chinese newspapers, pictorials, and science fiction (referred to as “kexue xiaoshuo,” 科学小说, at that time). In Shanghai, hypnosis performances and research seminars took place. For the history of hypnotism in modern China, see Zhang Bangyan’s 张邦彦 Jingshen de fudiao: Jindai Zhongguo de cuimianshu yu dazhong kexue精神的复调:近代中国的催眠术与大众科学 [The polyphonic psyche: Hypnotism and popular science in modern China] and Luis Fernando Bernardi Juniqueira’s “A Spiritual Revolution: Psychical Research and the Revival of the Occult in a Transnational China, 1900–1949.”

- From 1904 to 1911, The Longevity Company (Changming yanghang 长命洋行) advertised the “Longevity Electric Belt” (Changming diandai 长命电带) in Xinwen bao 新闻报 [The news], Shi bao时报 [The eastern times], Dagong bao 大公报 [Impartial daily], and Shen bao 申报 [Shanghai news]. The company sold the electric belt in branches in Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Hankou, Hong Kong, and Guangzhou.

- According to the annotation of the translated article, the original article was published in the 5th issue of 1962 of a journal, whose title was translated into Chinese as “Xinlixue wenti” (心理学问题, Problems of psychology). I was unable to locate the original article. The journal is likely Voprosy Psikhologii (Questions of psychology).

- The article is titled “Sulian xueshujie jinnia dui kongzhi lun zhexue wenti de taolun shifen renao” 苏联学术界近年对控制论哲学问题的讨论十分热闹 [In recent years the Soviet academic community had heated discussion on philosophical issues of cybernetics]. For the summary of the article content, see the editor’s note of Mao Zedong’s article “Zai ‘Sulian xueshujie jinnian dui kongzhi lun zhexue wenti de taolun shifen renao’ yi wen shang de pizhu.” 在《苏联学术界近年对控制论哲学问题的讨论十分热闹》一文上的批注 [Annotation on the article “In recent years Soviet academic community had heated discussion on philosophical problems of cybernetics”], Jianguo yilai Mao Zedong wengao 建国以来毛泽东文稿 [Selected works of Mao Zedong since the founding of the People’s Republic of China], vol. 10, Beijing: Zhongyang wenxian chubanshe, 1996, p. 434.

- Wiener’s concern about the misuse of cybernetics represents only one facet of this interdisciplinary field. Researchers have pointed out that the two major contributors to cybernetics, Wiener and John von Neumann (1903–1957), held significantly different views regarding the appliance and social implications of cybernetic ideas. Wiener’s approach was “based upon independent acts of conscience.” He insisted that any technical aspect of social systems should sustain and enhance human life. In contrast, John von Neumann’s mathematical axiomatic approach showed “an affinity for military authority and control” (Noble 71). The discourse surrounding cybernetics is permeated with tensions and ambiguity, as it combines liberal social ideas with militaristic attitudes.

- Researchers on post-socialist Chinese SF have noticed the intersections between robotic imaginations and societal governance. Virginia L. Conn, in her analysis of Wei Yahua’s SF story “Wenrou zhi xiang de meng” 温柔之乡的梦 [Conjugal happiness in the arms of morpheus], a story about a robot wife, argues that the hierarchy of labor in this story “replicated the ideological shift…from a Marxist-Leninist acknowledgement of transformative cultural production under Mao to the cybernetic model of control introduced with Zhou Enlai and actualized through Song Jian’s work under Deng Xiaoping” (96). Nevertheless, few studies have touched upon the complexity of the interaction between technological narratives and social control in Mao-era SF texts. In Chi Shuchang’s 迟叔昌 (1922–1997) “Renzao penti” 人造喷嚏 [The artificial sneeze], which was published in the same collection as “The Rural Doctor,” the school provides every student with a device resembling a watch. The watch turns out to be a “Medical Alert Transmitter” (bingqing fabao ji 病情发报机), capable of monitoring each individual’s health condition and sending alerts to the central computer at the Central Hospital if any issues arise (Chi 102–109). Within the Maoist context, this story conveys the idea that technology can assist people in the medical field. However, such a society with pervasive monitoring could possibly turn into a horrible dystopia if the monitoring is used by certain individuals or groups to increase their political, emotional, and biological control over the rest.

- Gianluigi Negro and Hongzhe Wang thinks that “[a]lthough the practical contribution of the Soviet Union was fundamental, Chinese policymakers, especially during the first years of the 1950s, were more inclined to support the American idea of cybernetics as well as the emerging American computer science” (254). However, as my study shows, China’s attitude toward cybernetics neither aligns with the American idea nor keeps the same with that of the Soviet Union.

WORKS CITED

Audette, Donald G. “Computer Technology in Communist China, 1956–1965.” Communications of the ACM, vol. 9, no. 9, 1966, pp. 655–661.

Cai Jingfeng 蔡景峰 and Zhao Shizhou 赵世洲. “Danao guangbo diantai” 大脑广播电台 [Brain broadcasting station]. Zhongguo shaonian bao 中国少年报, no. 889, 1963, p. 3.

Changming yanghang 长命洋行主人. “Qing kan diandai zhibing zhi yuanli” 请看电带治病之原理 [Please see the principle of using electric belt to treat diseases]. Shi bao时报, 22 Jun. 1905, p. 7.

Chi Shuchang 迟叔昌. “Renzao penti” 人造喷嚏 [The artificial sneeze]. Shiqu de jiyi 失去的记忆 [The lost memory], Tong Enzheng童恩正 et al., Shanghai: Shaonian ertong chubanshe, 1963, pp. 102–109.

“Control Theory.” ScienceDirect, http://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/computer-science/control-theory. Accessed 2 April, 2024.

Conn, Virginia Lee. The Body Politic: Socialist Science Fiction and the Embodied State. 2021. The State University of New Jersey, PhD dissertation.

Dai, Frank. “Xinxi guo” 信息锅 [Information pot]. Flickr, June 3, 2005, http://www.flickr.com/photos/undersound/23239355.

Dneprov, Anatoly [An Deniepuluofu 安·德涅普罗夫]. “Suaima: Yige jixieren de gushi” 苏埃玛:一个机械人的故事 [Siema: The story of a robot], originally titled “Суэма.” Translated by Yu Zuyuan俞祖元 and Gu Jingqing顾镜清. Kexue Huabao 科学画报, no. 1–3, 1963.

Editors. “Qingchu ‘Suaima’ suo sanbu de dusu” 清除《苏埃玛》所散布的毒素 [Clear toxins spread by “Suaima”]. Kexue huabao 科学画报, no. 7, 1966, p. 296.

Engels, Friedrich and Marx, Karl. The Holy Family: Or Critique of Critical Critique. Translated by R. Dixon. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1956.

Gerovitch, Slava. From Newspeak to Cyberspeak: A History of Soviet Cybernetics. MIT Press, 2002.

Hayles, N. Katherine. “Cybernetics.” Critical Terms for Media Studies, edited by Mark B. N. Hansen, W. J. T. Mitchell, University of Chicago Press, 2010, pp. 145–156.

Hayles, N. Katherine. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. University of Chicago Press, 1999.

“Jianxun: Disijie guoji kongzhilun huiyi” 简讯:第四届国际控制论会议 [News in brief: The Fourth International Congress on Cybernetics]. Ziran bianzhengfa yanjiu tongxun 自然辩证法研究通讯, no. 2, 1964, p. 34.

Jin Guantao 金观涛 and Liu Qingfeng 刘青峰. Xingsheng yu weiji: Lun Zhongguo fengjian shehui de chao wending jiegou 兴盛与危机: 论中国封建社会的超稳定结构 [The cycle of growth and decline: On the ultra-stable structure of Chinese society]. Wuhan: Hunan renmin chubanshe, 1984.

Junqueira, Luis Fernando Bernardi. “A Spiritual Revolution: Psychical Research and the Revival of the Occult in a Transnational China, 1900–1949.” The Media of Mediumship, http://www.mediaofmediumship.stir.ac.uk/2021/10/22/a-spiritual-revolution-psychical-research-and-the-revival-of-the-occult-in-a-transnational-china-1900-1949/. Accessed 6 May, 2024.

Li, Hua. Chinese Science Fiction during the Post-Mao Cultural Thaw. University of Toronto Press, 2021.

Liu Shiyi 刘世熠. “Kongzhi lun yu danao” 控制论与大脑 [Cybernetics and the brain]. Renmin ribao 人民日报, 20 Jul. 1959, p. 7.

Liu Xingshi 刘兴诗. “Xiangcun yisheng” 乡村医生 [The rural doctor]. Shiqu de jiyi 失去的记忆 [The lost memory], Tong Enzheng童恩正 et al., Shanghai: Shaonian ertong chubanshe, 1963, pp. 91–101.

Liu, Lydia H. The Freudian Robot: Digital Media and the Future of the Unconscious. University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Liu, Xiao. Information Fantasies: Precarious Mediation in Postsocialist China. University of Minnesota Press, 2019.

Lu San陆叁. “Weirao kongzhi lun kexue chengjiu de sixiang douzheng” 围绕控制论科学成就的思想斗争 [Ideological controversies over the scientific achievements of cybernetics]. Ziran bianzheng fa yanjiu tongxun, no. 1, 1963, pp. 2–6.

Mao Tse-tung. On Practice and Contradiction. Translators unknown. London and New York: Verso, 2007.

Mao Zedong 毛泽东. “Zai ‘Sulian xueshujie jinnian dui kongzhi lun zhexue wenti de taolun shifen renao’ yi wen shang de pizhu” 在《苏联学术界近年对控制论哲学问题的讨论十分热闹》一文上的批注 [Annotation on the article “In recent years the Soviet academic community had heated discussion on philosophical problems of cybernetics”]. Jianguo yilai Mao Zedong wengao 建国以来毛泽东文稿 [Selected works of Mao Zedong since the founding of the People’s Republic of China], vol. 10, Beijing: Zhongyang wenxian chubanshe, 1996, p. 434.

Mayijieer 马依捷尔 and Fatejin 法特金. “Sulian juxing kongzhi lun de zhexue wenti huiyi” 苏联举行控制论的哲学问题会议 [The Soviet Union held a conference on the philosophical problems of cybernetics]. Translated and excerpted by Xu Shijing 徐世京. Ziran bianzheng fa yanjiu tongxun 自然辩证法研究通讯, no. 1, 1963, pp. 48–50.

Negro, Gianluigi, and Wang, Hongzhe. “Computing the New China. The Founding Fathers, the Maoist Way, and Neoliberalism, 1945–1986.” Prophets of Computing: Visions of Society Transformed by Computing, edited by Dick van Lente, Association for Computing Machinery, 2022, pp. 247–278.

Noble, David F. Forces of Production: A Social History of Industrial Automation. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2011.

Peng Yongdong 彭永东. “Kongzhi lun sixiang zai Zhongguo de zaoqi chuanbo (1929–1966)” 控制论思想在中国的早期传播(1929–1966年)[The early diffusion of cybernetics in China (1929–1966) ]. Ziran kexueshi yanjiu 自然科学史研究, vol. 23, no. 3, 2004, pp. 299–318.

Qin Yongnian 秦永年. “‘Suaima: yige jixieren de gushi’ xuanyang le shenme guandian” 《〈“苏埃玛”——一个机械人的故事〉一文宣扬了什么观点》[What kind of idea “Suaima: A Robot’s Story” conveyed]. Ziran bianzheng fa yanjiu tongxun 自然辩证法研究通讯, no. 2, 1966, pp. 44–45.

Rosenblueth, Arturo, Wiener, Norbert, and Bigelow, Julian. “Behavior, Purpose and Teleology.” Philosophy of Science, vol. 10, no. 1, 1943, pp. 18–24.

Stroud, John. “The Psychological Moment in Perception.” Cybernetics: The Macy Conferences 1946–1953, edited by Claus Pias, Zurich and Berlin: Diaphanes, 2016, pp. 41–65.

Tan Sitong 谭嗣同. Renxue 仁学 [An exposition of benevolence]. Shenyang: Liaoning renmin chubanshe, 1994.

Tong Enzheng 童恩正. “Shiqu de jiyi” 失去的记忆 [The lost memory]. Shiqu de jiyi 失去的记忆 [The lost memory], Tong Enzheng童恩正 et al., Shanghai: Shaonian ertong chubanshe, 1963, pp. 1–20.

Wei Yahua 魏雅华. “Qiyi de anjian” 奇异的案件 [A curious case]. Qiyi de anjian 奇异的案件 [A curious case], Xi’an: Shanxi renmin chubanshe, 1981, pp. 58–75.

Wiener, Norbert. Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. MIT Press, 1965.

Wiener, Norbert. The Human Use of Human Beings: Cybernetics and Society. London: Free Association Books, 1989.

Wu Yunzeng 吴允曾. “Jiqi yu siwei” 机器与思维 [Machine and thinking]. Renmin ribao 人民日报, 24 May. 1965, p. 5.

Xiao Jianheng 萧建亨. “Qiyi de jiqigou” 奇异的机器狗 [A strange robot dog]. Shiqu de jiyi 失去的记忆 [The lost memory], Tong Enzheng童恩正 et al., Shanghai: Shaonian ertong chubanshe, 1963, pp. 21–57.

Xiao Jianheng 肖建亨. “Tie bizi de gushi” 铁鼻子的故事 [The story of the iron nose]. Women ai kexue 我们爱科学, no.11, 1964, pp. 64–77.

Xu Nianci 徐念慈. “Xin faluo xiansheng tan” 新法螺先生谭 [New Tales of Mr Braggadocio]. Xin faluo 新法螺 [New Mr. Braggadocio], Shanghai: Xiaoshuolin she, 1905, pp. 35–39.

Ye Biao 叶飙 et al. “Shei wei qigong jueqi baojiaohuhang ‘dashi’ beihou de darenwu” 谁为气功崛起保驾护航 “大师”背后的大人物 [Who escorted the rise of qigong? Key figures behind “great masters”]. Nanfang zhoumo 南方周末, http://www.infzm.com/contents/93185?source=202&source_1=93184. Accessed 3 May, 2024. Zhang Bangyan 张邦彦. Jingshen de fudiao: Jindai Zhongguo de cuimianshu yu dazhong kexue 精神的复调:近代中国的催眠术与大众科学 [The polyphonic psyche: Hypnotism and popular science in modern China]. Taipei: Lianjing chubanshe, 2020.

Ruiying Zhang is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Asian Studies at Cornell University. Her research interests lie in the history of science and technology and the narrative of science, technology, and media in modern and contemporary China.