Fiction Reviews

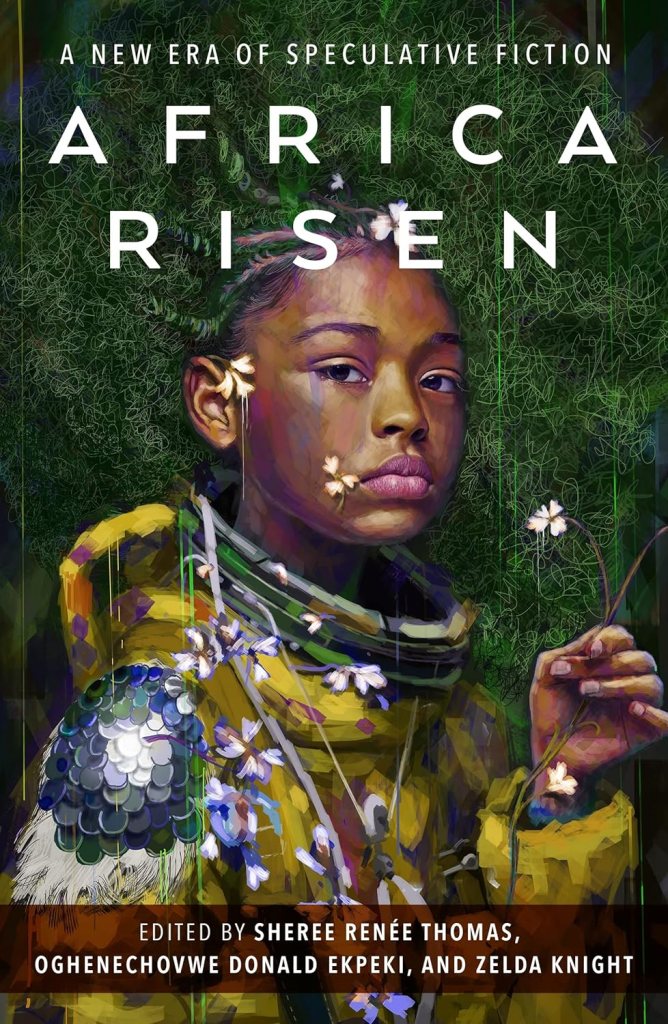

Review of Africa Risen: A New Era of Speculative Fiction

Reo Lewis

Tesh, Emily. Some Desperate Glory, Tor Publishing Group, 2023.

Twenty-four years ago, the goal of the prolific African-American writer and editor Sheree Renée Thomas in her highly-regarded anthology Dark Matter: A Century of Speculative Fiction from the African Diaspora (2000), was to “correct the misperception that black writers are recent to the field” (6). There is perhaps no better testament to the achievement of her goal than the ever-growing list of science-fiction and fantasy anthologies centring authors from Africa and its diaspora since Dark Matter’s publication: from Nalo Hopkinson’s So Long Been Dreaming: Postcolonial Science Fiction and Fantasy (2004) to Nisi Shawl’s New Suns: Original Speculative Fiction by People of Color (2019) and Dominion: An Anthology of Speculative Fiction from Africa and the African Diaspora (2020), edited by Thomas’ collaborators Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki, and Zelda Knight. The editors of Africa Risen no longer have to convince their readers that black writers are prolific in this genre because, to anyone with more than a passing familiarity with science-fiction and fantasy, the point has already been made. With the burden of proof removed from their shoulders, the stories in Africa Risen are free to “continue the mission of imagining, combining genres and infusing them with tradition, futurism, and a healthy serving of hope” (4). Undoubtedly, it is in the moments when this anthology takes advantage of this unimpeded creative and cultural freedom that the stories shine best.

From the contents page alone, Africa Risen begins to impress readers with the names of included speculative literary giants such as Tananarive Due and Steven Barnes. Barnes’ story “IRL” is the first real stand-out of the collection, a cyberpunk-esque exploration of black masculinity and fatherhood with characters motivated by the drive to provide for one’s family and community against the obstacles of corruption in the economic, justice, and healthcare system. It is a story that legitimises the use of escapism and worldbuilding as tools of survival. “IRL” quickly proves itself to be among good company with the other stories of Africa Risen. Wole Talabi’s “A Dream of Electric Mothers” turns bureaucratic indecision into an opportunity to commune with a digital ancestral hivemind, with a main character who finds resolution and strength through her maternal lineage. “The Sugar Mill” by Tobias S. Buckell is also about ancestral communion, except this time in the form of a ghost story with the intimate feel of a family drama rather than a campfire horror tale. Haunting manifests through bloodlines of trauma—the ghosts haunt the land where their blood was spilt and they haunt their descendant who carries their blood and the haunting doesn’t end until they are properly memorialised and safeguarded against neo-colonisers who would disregard their pain and their history. “The Lady of the Yellow-Painted Library” by Tobi Ogundiran (a story which has gained popularity after being featured on an episode of the podcast Levar Burton Reads) reads like an episode of The Twilight Zone, exploring the inescapable and cyclical burden of responsibility using an African Literature classic, Things Fall Apart, as the plot’s MacGuffin— the object that serves to set and keep the plot in motion despite usually lacking intrinsic importance, like The One Ring in The Lord of the Rings. “Hanfo Driver” by Ada Nnadi is a slice-of-life tale with casually diverse characters and a realistic view of how technological disparity will continue in the future, leading to a relatively low-stakes conflict and heartwarming humour.

With just a quick summary of these five standout stories, it is clear the impressive range of settings, themes, and characters that appear in Africa Risen. However, as to be expected with an anthology of thirty-two stories, not all of them work as well as the others. There are many stories in Africa Risen that lead the reader to think, “Didn’t I just read a better version of this a second ago?” But these choices come across as intentional rather than redundant. These stories are in conversation with each other, with the writer, and with the SFF generic tradition. Just because “Cloud Mine” by Timi Odueso is the eco-dystopia from a child main character’s point-of-view that resonated most with me due to its lens of systemic abuse and labour exploitation, it doesn’t mean another reader wouldn’t prefer Dilman Dila’s “The Blue House,” Russell Nichols’ “Mami Wataworks,” or Moustapha Mbacké Diop’s “When the Mami Wata Met a Demon.” Likewise, while Alexis Brooks de Vita’s “A Girl Crawls in a Dark Corner” is a standout for me, others might prefer the alternate history retelling of WC Dunlap’s “March Magic” or the feminist horror of Mame Bougouma Diene and Woppa Diallo’s “A Soul of Small Places.” “Liquid Twilight” by Ytasha Womack is a mermaid story with a cinematic feel and captivating characters who treat speculative work as a form of activism and vice versa, but another reader might prefer the representation of activism in Akua Lezli Hope’s “The Papermakers.” Stories within an anthology are collaborative, not competitive. The fact that many of these authors chose to write about similar topics only reinforces the importance of these themes in literature in general. These stories are just as concerned with the role of history, tradition, and ancestry as they are with futurism. These worlds are fully realised: there are no dystopias without hope and activism towards change and there are no utopias without realism and a critique of the status quo. And for every story that felt like it was treading familiar ground, there was also a story which had something new to say, whether it was about misogyny and trauma exploitation in the music industry (“Peeling Time (Deluxe Edition)” by Tlotlo Tsamaase), PTSD and the exploitation of child soldiers (“A Knight in Tunisia” by Alex Jennings) or the African-American fantasy of Pan-African return (“Ruler of the Rear Guard” by Maurice Broaddus). By the time you reach the end of the collection, you truly feel like you have experienced a cohesive yet diverse presentation of thirty-two Afro-speculative worlds.

As with any anthology, there isn’t space to review every story, but there is one story that it would be remiss not to mention as, in my opinion, “Air to Shape Lungs” by Shingai Njeri Kaguda, is emblematic of what Africa Risen is all about. Although it is not the diaspora story the editors chose to end the collection with (Dare Segun Falowo’s “Biscuit & Milk” gets that honour), to me it is the diaspora story of the anthology, the one that best narrates the feeling of home-seeking and anti-rootedness of the diaspora experience through a disembodied, airborne, communal “we” voice. It is narrated in two alternating sections, “Memory” and “Living Now,” which summarise perfectly the concerns of the authors throughout the collection. Speculative fiction is most often associated with futurism, but in the hands of these African and Afro-diasporic authors, speculative fiction is equally about the legacies of the past and the concerns of the present as it is about the imagination of the future. Africa Risen may not be revolutionary in the way Dark Matter was, but it is not the job of black writers to revolutionise with every story they tell: black speculative fiction writers, like all speculative fiction writers, only need to be allowed space to have fun, to debate, to explore and to innovate. Undoubtedly, with Africa Risen, Sheree Renée Thomas, Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki, and Zelda Knight have once again provided that space for African and Afro-diasporic authors to thrive.

Reo Lewis is a graduate of the MA in Comparative Literature from SOAS, University of London. She is currently a Creative Writing PhD candidate at the University of Exeter, with research at the intersection of speculative fiction, linguistics and diaspora studies. Her project is a short story collection that explores how the use of diasporic speech in fantasy and science-fiction worlds can contribute to decolonising the tropes of these genres.