Fiction Reviews

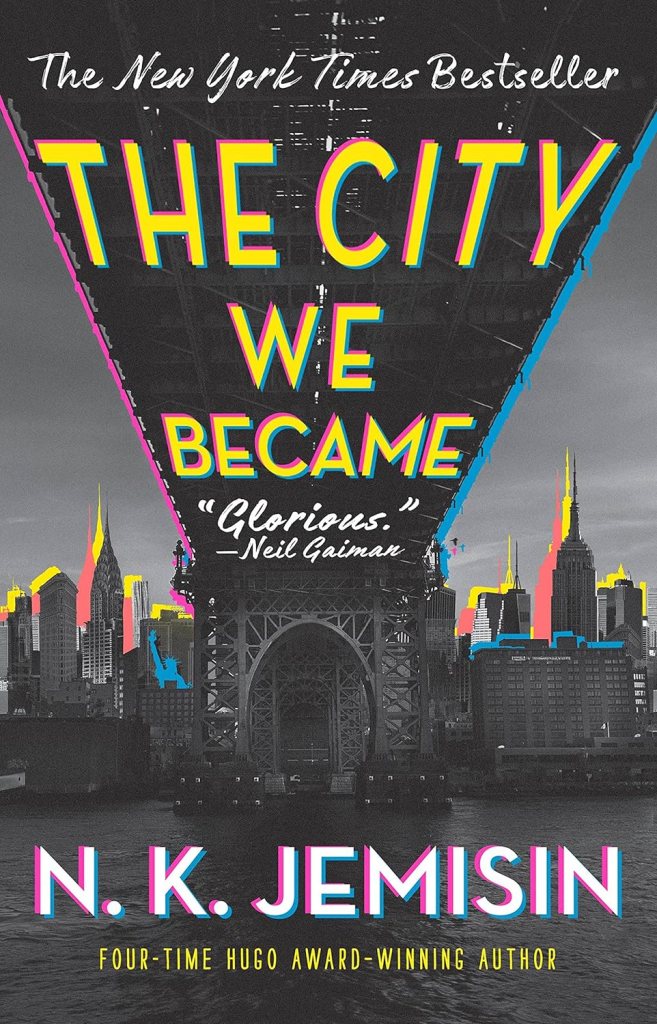

“Cities really are different. They make a weight on the world, a tear in the fabric of reality, like… like black holes, maybe”. The opening words of N. K. Jemisin’s 2020 novel The City We Became provocatively hint at the liminality of the spaces occupied by people and cityscapes. The very essence of a city is created by the nuances of its residents and the ways in which they interact with each other and the material objects that make up the topography of that specific space. Jemisin often addresses this interdependent tension in her works by implementing a kind of literary stratigraphy, uncovering layers of complex systems and external factors that determine the identity of any given city. In The City We Became, Jemisin develops her original short story, “The City Born Great,” which was published in her 2018 collection How Long ‘Til Black Future Month?.

The protagonist in the short story, an unnamed, black, homeless youth is chosen by the city as a midwife to assist in New York’s birth. The City We Became picks up the narrative after a difficult and not entirely successful birth, leaving the character in a coma-like condition hidden beneath the surface, both literally and in terms of plot. While this character remains fragmentary and elusive, five avatars, each representing a different borough of New York, take center stage in the quest to deal with postpartum complications. These avatars each capture the diverse collective characteristics of the sum parts that make up the whole city, and, although they are drawn together to defeat the mysterious and menacing enemy who appears in the guise of an almost translucent “woman in white,” their individual differences cause friction as they are territorial and defensive.

These differences are identified in the way they communicate: Bronca (Bronx), speaks through art; Brooklyn (Brooklyn), via political language and the rhythm of hip hop; Padmini (Queens), utilizes mathematical equations; Manny (Manhattan), employs violence, particularly in his previous iteration, and the language of economics; and Aislyn (Staten Island), lacking a voice, has no means of communicating effectively and is easily manipulated by the enemy

Jemisin draws on the familiar tropes of speculative fiction and Afrofuturism—supernatural beings, myths, and spatio-temporal liminal gaps, in this case portals to multiverses—to reveal the fragile nature of this emerging city and the potential for other histories, existences, and futures. Interestingly, the avatars have hallucinatory visions of another reality of New York, although they don’t physically enter it. Jemisin plays with the theory of multiverses attempting to overlay each other in a palimpsestic manner. Bronca, the First Nation character, is used as storyteller to explain the idea of many worlds, which resonates with Neil de Grasse Tyson’s explanation of the hypothesis (Science Time); she then goes on to outline how worlds are constantly created through imagination (Jemisin 302).

The topography of the boroughs, islands separated by water and bridges, mirrors the flickering, “peculiar dual-boot of reality,” whereby people and places are connected and disconnected by perspectives (32). It is this apparent glitch between worlds or realities that is presented as being dangerous to the city’s “becoming” and the population who make up the city’s identity. Tendrils of white ominous nubs rise from cracks in the asphalt and seep into the “normal” New York, threatening to contaminate and obliterate that version of reality.

Explicit references to H.P. Lovecraft’s bigoted view of non-white people are made through an alternative reality, a city whose identity is produced by a specific, limited worldview represented by the sinister “woman in white” (the embodiment of Lovecraft’s demonic R’lyeh). The only avatar to align herself to this perspective is Aislyn (Staten Island) as she is already stunted by fear and self-imposed isolation. It is not surprising that Aislyn is the only white avatar as she represents the insidious effects of racism that run counter to and are threatened by the diversity of the population.

The woman in white determines that the “acculturation quotient is dangerously high,” and this is the sticking point for those like Aislyn whose phobias close off their minds to embracing difference (96). A city is born when “enough human beings occupy one space, tell enough stories about it, develop a unique culture, and all those layers of reality start to compact and metamorphose” (304). Jemisin draws on the history of Staten Island to highlight its arbitrary and tenuous connection to the city, hence its resistance to support the other boroughs and protect the vulnerable, primary avatar. The enemy, which is a city itself from an alternative reality, eventually becomes caught between realms. This sense of in-betweenness is the crux of the narrative, what could or would be if other dynamics were more dominant. In a final attempt to anchor itself into existence, the enemy clings to Staten Island, thus opening the way for the second book in this series, The World We Make.

Jemisin expertly captures the essence of what makes New York the city it is and creates complex, imperfect characters that embody that spirit. Her insight into the relationship between humans and the cityscapes they occupy is unique, thereby positioning her as an award-winning, leading author in this genre. Not only has she been nominated for and won numerous awards, including Locus, Nebula, and Tiptree, Jemisin is the only recipient of three consecutive Best Novel Hugo Awards and the recipient of the MacArthur Fellows Program (2020). Jemisin deftly incorporates her observations and experience of living in New York to reveal possibilities and challenge realities. The City We Became addresses many of the issues that are faced by modern-day populations in a way that is familiar, understandable, and raw, but, importantly, hopeful. The energy that overcomes the enemy emanates from the city itself, its sights and sounds mimicking a heartbeat. Once again, Jemisin adeptly peels back the layers to reveal the soul of the city in a way only she can.

WORKS CITED

“The Multiverse Hypothesis Explained by Neil deGrasse Tyson.” YouTube, Uploaded by Science Time 28 Nov 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h6OoaNPSZeM.

Heather Thaxter is a PhD candidate by published works which include book chapters in The Bloomsbury Handbook to Octavia E. Butler and Introduction to Afrofuturism: A Mixtape of Black Literature and Arts. Heather’s research interests are Afrofuturism, postcolonial studies, and speculative fiction with a special interest in Octavia E. Butler. Currently employed as a lecturer, Heather is also on the Editorial Review Board of Essence and Critique: Journal of Literature and Drama Studies. ORCID number: 0000-0001-9473-6200.