Fiction Reviews

Review of A Half-Built Garden

Jeremy Brett

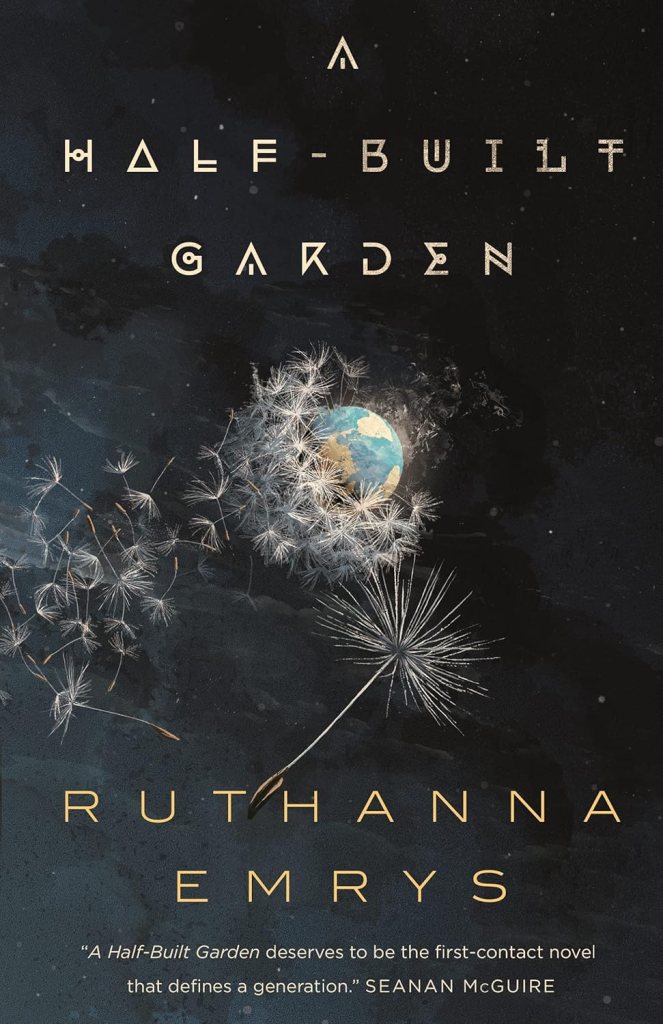

Ruthanna Emrys. A Half-Built Garden.Tordotcom, 2022. Paperback. 340 pg. $18.99. ISBN 978-1-250-21099-9.

After enough time, one might be forgiven in thinking that there can be no new First Contact stories to tell. It’s a truly singular event when an author takes a classic sf trope and spins it in a new direction infused with existential social and political relevance. This sort of literary shift was already accomplished by author Ruthanna Emrys in her “Innsmouth Legacy” series, in which she infused the classic Lovecraftian universe of cosmic horror with empathy and feeling for the marginalized in opposition to the racism endemic to Lovecraft and his era. With A Half-Built Garden, Emrys brings modern and lasting concerns for the future of humanity and Earth (which the novel takes pains to point out are not, to certain people, the same thing at all) to a wholly unusual and thoughtful story of alien encounter.

In 2083, the Earth has been engaged for several decades in a radical moment of social, political, and corporate restructuring. Nation-states have been replaced or supplemented by networks centered on the maintenance, restoration, and care of environmentally critical watersheds. The rampant capitalists that ravaged the planet in the 20th and 21st centuries have for the most part been reduced to small island enclaves, connected to the watershed networks and traditional governing structures in uneasy alliances of trade and supply. The networks, which sprung into existence as part of the Dandelion movement (the image, of course, suggesting seeds being spread by the free flow of the wind) govern themselves through collaboration, consensus, and intimate communication rooted in problem-solving. The Dandelion networks devote themselves to repairing what had been so desperately, horribly broken in the world by capitalism and nationalism. Adaptation and harmony are increasingly default human values, and for the first time, despite ongoing struggle, there is hope.

And then the aliens landed. So goes the cliché, but one thing that makes Emrys’ novel so particularly remarkable is the response from this altered world. The novel avoids chronicling an all-out defensive reaction from the militaries of the world, frenzied government scrambling, mass panic (in fact, among the most striking aspects of the book is the immediate acceptance by humans of the aliens as they walk among us), or the complete absence of panic or fear. Those responses are replaced instead with curiosity, acceptance, honest attempts at connection and friendship, attempts at exploitation (by the capitalists), and even sexual exploration (by protagonist/narrator Judy and her wife Carol with the alien representative Rhamnetin). Alien encounters, Emrys posits, bring out the full range of human behavior in people; we are not limited to our most atavistic responses. This attitude of optimism denotes the novel’s true throughline. We see it from the very opening, in which Judy notes “In the bad old days (the commentary said later), nation-states had plans laid in for this sort of thing. They’d have caught the ship on satellite surveillance. They’d have gotten in the ground with sterile tents and tricorders and machine learning translators, taking charge. In a crisis, we still look for the big ape.” However, “instead of a big ape shouting orders, the world got me.” (1) Humble Judy, of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Network, becomes the Earth’s first ambassador to alien life after stumbling across a crashed spaceship – and, as she points out “That would have been a good time for cynicism – for someone to ask if we believed them, or if their definition of peace looked anything like ours. But no one wanted to spoil the moment of joy. We didn’t want to play nation-style realpolitik, or be properly mature and suspicious. We wanted to talk. However complicated things got afterward, I still can’t regret that.” (6) In Half-Built Garden, hope in peaceful connection is a precious resource and a defense against a hostile universe.

And that hope is crucial, because the aliens have brought a choice that seems to be no choice. The aliens are comprised of multiple species (represented on this mission by the spider-like “tree folk” and the more insectile “plains folk”) from the Rings, a system of artificial worlds that exists because the Ringers have determined that all intelligent life inevitably destroys its own homeworld and must go into space to survive. Having discovered humanity before it’s too late, they bring an offer—really, more of a predetermined conclusion—to evacuate the planet and move humans out to the stars. The corporates jump at the chance, ready to leave Earth and reestablish their shattered traditions of dominance and power among new, alien markets. Nation-states (represented here mainly by NASA as the avatar of a reduced American government) are driven by curiosity and excitement to see what’s out there. However, the Dandelion networks have invested decades of rescue in trying to stabilize and repair the environment, and Judy, Carol, and the people who comprise those networks are not prepared to surrender their home for which they have fought so hard. The novel turns on this existential-level decision, and on the multiple conversations between and among humans and Ringers on humanity’s future. Emrys places the need for radical and trusting connection at the story’s center, the crucial importance of reaching for understanding across vastly divergent mindsets and motives.

A debate between the Ringers and Dandelion representatives towards the end of the novel summarizes these differing views of the universe that each party holds. Judy, the descendant of a traumatized humanity that teetered on the verge of self-destruction (as well as being Jewish and therefore a custodian of a tragic tradition of forcible wandering), points out that “It’s good to live in a time when we have a time we can love. Someplace we can afford to grow attached to.” One of the Ringers, Glycine, responds “But many of us believe you have to drag people out of a burning building, whether they love the building or not. The question is whether Earth is burning.” Judy’s friend and colleague Atheo fires back, “It’s burning…Well, it’s true. But we’re getting the fire under control. It’s a matter of whether you trust us to know the resilience of our own home, whether you treat us as adults who can calculate our own risk rather than kids who don’t know any better” (256). Emrys follows the traditional pattern of a story of alien contact in casting it as a moment for exploring the nature of humanity in the face of an overwhelming and world-changing event; her twist is presenting it as a time of choosing, not merely whether humanity will survive at all, but how and where. She asks the questions: is our home planet, the only home we have ever known as a species, integral to our identity? Will we be the same, and if not, how will we change, if we actually leave Earth and become part of a wider universe? Most critically, if motives are so different, can a true symbiosis between species and the creation of new families and alliances be achieved?

The novel proposes that an informed exchange and sharing of ethical values, together with recognition of differences among ourselves, is the key to effective symbiosis and the bridging of ideological divides. Judy at one point speaks of “the value and the means to achieve it. I’m trying to tell you [the Ringers] that we share the value. Our ancestors either didn’t share it, or didn’t act on it, but we do. And we do because we’ve developed technology for not only identifying our values, but for consistently acting on them” (318). And the trans character Dori offers her coming out as a gift to the Ringers, noting that her parents loved who and what she was more than what they expected her to be. She tells the Ringers that “we can use your gifts in ways you don’t expect, too—if you can cope with us using different means to achieve our shared values. Your technologies for making habitats livable could help save Earth…Symbiosis with Ringers could give us both new tools, new ways to survive in a cold universe” (319). The Dandelions ask an alien society averse to risk and afraid of catastrophe to take a chance on humanity’s potential and its promise, to let systems go unconstrained. In that request lies the continuation of the hope and determination that brought humanity out of its age of power into the late 21st century age of nature. The “half-built garden” of the title in the end, we find, is not only an Earth slowly and gradually being wrested from destruction, but a species just beginning to understand its possible role in a new and symbiotic galaxy.

Jeremy Brett is a Librarian at Cushing Memorial Library & Archives, where he is, among other things, the Curator of the Science Fiction & Fantasy Research Collection. He has also worked at the University of Iowa, the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, the National Archives and Records Administration-Pacific Region, and the Wisconsin Historical Society. He received his MLS and his MA in History from the University of Maryland – College Park in 1999. His professional interests include science fiction, fan studies, and the intersection of libraries and social justice.