Media Reviews

Review of Executive Order

Alfredo Suppia

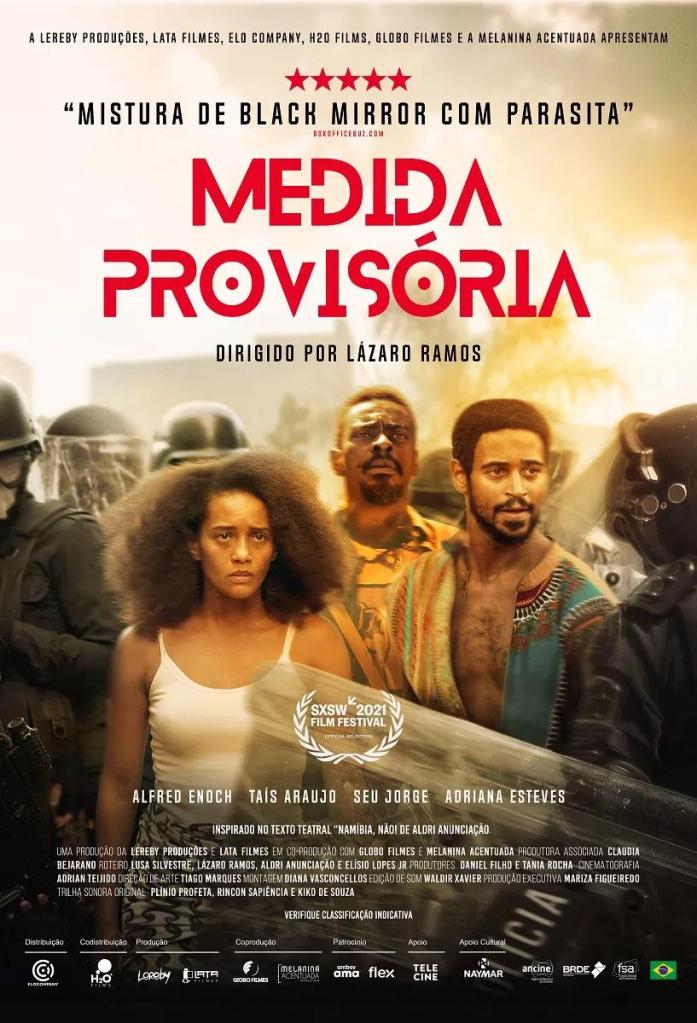

Executive Order (Medida Provisória). Dir. Lázaro Ramos and Flávia Lacerda. Lereby Produções; Lata Filmes; Globo Filmes; Melanina Acentuada, 2020.

One of the most meaningful parables to date against the structural racism deep-rooted in Brazilian society and the historical social and economic debt to African-Brazilians publicly appeared in 2021 as a feature-length film that conveys an alarming dystopian tale. Directed by Lázaro Ramos in collaboration with Flávia Lacerda (co-director), Executive Order is set in a near-future Rio de Janeiro, when the Brazilian government is sued by the young, successful lawyer Antônio Gama (Alfred Enoch) and condemned to pay massive reparations to all citizens descending from enslaved Africans. The authorities see the just reparation as the State’s utter financial collapse. Thus, the authoritarian government responds by decreeing the exile of all black citizens (now addressed as “accentuated-melanin citizens”, a term used almost verbatim in Shalini Kantayya’s documentary Coded Bias, 2020) to Africa as an alternative to repaying the debts of slavery—this operation immediately reveals itself as a new wave of eugenics with the “desirable” whitening of Brazilian society. Citizens are measured by their skin color, captured, and sent to Africa against their will. While the army and police enforce the law, Antonio gets involved in a personal drama as he, his uncle André Rodrigues (Seu Jorge), and his wife Capitu (Taís Araújo) become victims of the authoritarian State, along with millions of other people. Capitu, a doctor, goes missing after a hospital shift amid the announcement of the decree and the beginning of the find-and-capture operation. She eventually finds an underground resistance movement known as the “Afrobunker.” The trio fights the madness that has taken over the country and joins the resistance that inspires the people.

This nationwide state operation is not free from opposition. Many “accentuated-melanin citizens” refuse to be banished, and “partisan” cells begin to appear. The most significant being the underground Afrobunker community, shaped after the old Brazilian quilombos that provided free life and safety for runaway enslaved people. As a “neoquilombo”, the Afrobunker is the most exciting and stimulating fictional premise within Executive Order. It is a place of resistance that once served as a get-together for lovers and Carnival partygoers (as the authoritarian State has forbidden Carnival). In the wake of the decree, the Afrobunker stirs a peaceful communal strategy for resistance reminiscent of the long-lasting “institution” of Brazilian Carnival, the quilombos, and even contemporary favelas and urban “occupations.” Note that black people in Executive Order do not handle firearms with ease, contrary to the notion that guns are a usual item in their daily lives as shown in countless other films set in favelas with black actors as drug dealers. This is highlighted by Lázaro Ramos (Medida Provisória: Diário do Diretor. Rio de Janeiro: Cobogó, 2022, 78) and does make a difference. The Afrobunker and the main characters’ acts of resistance are primarily peaceful and not driven by revenge.

Above all—and this can be seen in a pivotal scene towards the end of the film, set in the Afrobunker—the characters’ choice is for civilization instead of brutality, collective engagement, empathy, and solidarity as a more profound and successful response to state authoritarianism and the long-lasting history of racial inequality. The trio of main characters performs a final scene that stresses this choice, eventually resorting to ingenuity instead of violence. The film’s ending remains open to further speculation with a clear nod at a promising future that encompasses a sort of national epiphany.

As told by Lázaro Ramos, Executive Order derived from his experience as director of Aldri Assunção’s play “Namíbia, No!”. Excited with the play’s reception and potential, Ramos decided to adapt it into a feature-length film along with Aldri Assunção, Lusa Silvestre, and Elísio Lopes Jr., co-authors of the screenplay. The film entered the production stage in 2019, before the outbreak of Covid-19 and during the first months of Jair Bolsonaro’s government. As Lázaro Ramos explains, the film was never meant to attack the Bolsonaro administration overtly: “Yet, if some of the attitudes of this government bear similarity to our story, the problem is not fictional, it’s reality” (76). Ramos (2022) and film critics often mention Black Mirror and The Handmaid’s Tale while addressing Executive Order. However, it is worth recalling more radical, experimental cinematic approaches to near-future utopias/dystopias, such as Lizzie Borden’s Born in Flames (1983) or Peter Watkins’s Punishment Park (1971).

Executive Order was completed at the beginning of 2020 and prepared for theatrical release. But Covid-19 had a tremendous impact on the film’s future. By the time the world’s film festivals and film markets had adapted to the pandemic, bureaucratic problems involving the National Film Agency and the Federal Court of Accounts further delayed Executive Order’s Brazilian premiere. The press and public expressed fear and suspicions about possible censorship imposed by the Bolsonaro administration. Executive Order’s avant-premiere took place at the South by Southwest Film Festival in Austin, Texas, in March 2020.

If, on the one hand, the pandemic was highly unfavorable to the film’s release, it may have, on the other hand, made Executive Order seem even more “attached” to reality. For instance, due to budgetary restraints, Ramos decided to reduce the number of police officers involved in the operation against African-Brazilians. The director imagined a future in which all law enforcers work masked, optimizing the reduced number of actors playing these agents (69). This visual motif is reminiscent of previous cinematic dystopias (e.g., George Lucas’s 1971 film THX-1138) and simultaneously addresses the reality of the pandemic.

Executive Order can be seen as a thought-provoking parable that may also illustrate, involuntarily or not, some of Sílvio Almeida’s main concepts in his book Structural Racism (Racismo Estrutural. São Paulo: Jandaíra, 2020). Almeida’s book revolves around two main arguments. First, contemporary society still cannot be fully understood without the concepts of race and racism. Second, to fully understand race and racism, it is crucial to master social theory. In other words: “the institutions are racist because the society is racist” (2020, 47). Almeida pragmatically considers racism as a “technology” which is instrumental to modern States under capitalism throughout its colonial and imperialist stages. Such “technology” still impregnates judicial systems and state administrations worldwide, justifying governments’ reproduction of violence and guaranteeing the economic elites’ hegemony.

Indeed, structural racism as a theory is far more complex than any single film. Executive Order is one of many cinematic representations that partially address the issue. Ramos’s film could be added to a “galaxy” of Brazilian shorts and feature-length films that revolve around this problem, in part or integrally. To name just a few: Sabrina Fidalgo’s Personal Vivator (2014), Eduardo and Marcos Carvalho’s Chico (2016), Diego Paulino’s Negrum3 (2018), Grace Passô’s República (2020), and the Netflix streaming series 3%. Films like Juliano Dornelles and Kléber Mendonça Filho’s Bacurau (2019), and Kléber Mendonça Filho’s Cold Tropics (Recife Frio, 2009), both tackle structural racism, yet under a white director’s perspective. The extrapolative dystopia of Executive Order, though, is remarkably familiar, as if the story might have happened in Brazil just “the day after tomorrow” during the Bolsonaro era. Fortunately, that era is gone—for the time being.

WORKS CITED

Almeida, Sílvio. Racismo Estrutural. São Paulo: Sueli Carneio/Ed. Jandaíra, 2020.

Alfredo Suppia is an Associate Professor at the Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp), Brazil, where he teaches film history and theory, science fiction cinema and new media art at the Department of Multimeios, Media and Communications. He also coordinates the Graduate Program in Social Sciences at the same university.