Fiction Reviews

Review of Africa Risen: A New Era of Speculative Fiction

Jeremy Brett

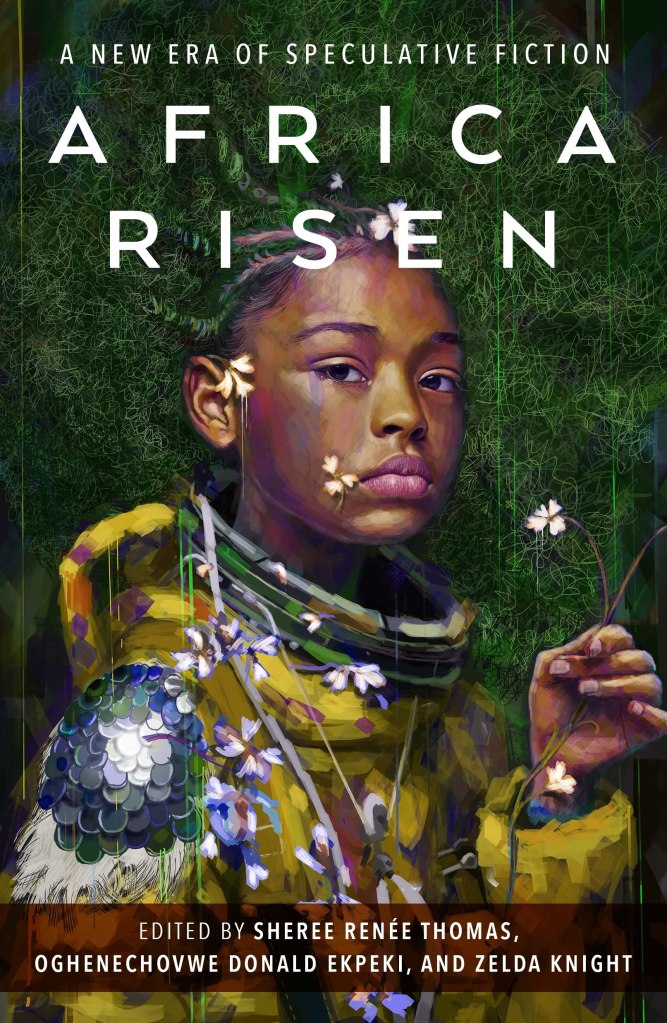

Thomas, Sheree Renee, Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki, and Zelda Knight, eds. Africa Risen: A New Era of Speculative Fiction. Tordotcom, 2022.

The increasing exposure to the Western world of narrative traditions, subjects, and cultures outside its traditional worldview is one of the brightest trends in science fiction and fantasy today. These traditions have always existed and been a part of the human penchant for storytelling, of course, but for so long they remained, at best, occasional adjuncts by most readers and critics to the “standard” literary products of the Western sf/f traditions. However, African and Afro-Diasporan creators are moving more and more to the forefront, thanks in large part to recent collections such as Sheree Renee Thomas’ pioneering Dark Matter: A Century of Speculative Fiction from the African Diaspora (2000) and its follow-up Dark Matter: Reading the Bones (2005), Bill Campbell and Edward Austin Hall’s Mothership: Tales from Afrofuturism and Beyond (2013), Nisi Shawl’s World Fantasy Award and BFA-winning New Suns: Original Speculative Fiction by People of Color (2019, 2023), Zelda Knight and Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki’s BFA-winning Dominion: An Anthology of Speculative Fiction from Africa and the African Diaspora (2020), and so many others; to newer online venues like FIYAH Magazine of Black Speculative Fiction; and Black-led publishing ventures such as MVmedia. Writers from Africa and the African Diaspora such as Ekpeki, Nnedi Okorofor, Tade Thompson, Tochi Onyebuchi, Sofia Samatar, Wole Talabi, Tloto Tsamaase, Eugen Bacon, and Namwali Serpell exponentially enrich the experience of encountering sf/f.

So, then, the arrival of Africa Risen is less unprecedented and more another reminder – expressed as a wildly varied package of beautifully created content – that African and Afro-Diasporan voices demand and deserve wider exposure as well as a greater portion of sf readers’ and publishers’ attention, that there have always been multiple, not to say infinite, creative possibilities for examining our shared human future, and that African speculative fiction is, in fact, here and has always been with us. As the editors note in the collection’s introduction, “[r]emember that this is a movement rather than a moment, a promising creative burgeoning. Because Africa isn’t rising – it’s already here” (4). The book presents its readers with thirty-two highly individual visions of where African sf is going, not limited by age, or gender, or national borders, or life experience. In doing so, the editors have produced a work that provides an impressive and multifaceted introduction for new readers looking to explore those aforementioned creative possibilities, and if, in the process, African and Afro-Diasporan speculative fiction can achieve wider ranges of reader attention and enthusiasm, that is truly all to the good and bodes well for future instances of creative richness in the genre.

Certainly, no readable review of any collection can provide detailed descriptions of every story in it, so I restrict myself here to highlighting several of the ones I think are the most interesting (well-written is not the defining factor here, since all the stories contained therein are worthy of praise for their style and writing quality—a tribute not only to the writers themselves but to the collection’s editors for their judicious powers of content selection). Several of the stories involve intimate connections with the electronic world: Steven Barnes’ “IRL” has particular value in these days of increased online presences, in its story of young Shango, who spends much of his time in the Void (a virtual Earth of fantasy kingdoms where ordinary people can exercise outsized, dramatic influence on their fellows) but who ultimately manipulates that fantasy world to affect his real emotional and financial existences. With “A Dream of Electric Mothers,” Wole Talabi gives us a future Oyo State where governance is directed by the collective memory of generations of ancestors preserved in a national data server and accessed through induced REM sleep. The story is a beautiful meditation on the power of memory and the advantageous necessity of political consensus. In Ada Nnadi’s lively and humorous “Hanfo Driver,” the beleaguered Fidelis, grubbing for freelance employment in Lagos, finds himself roped into his friend Oga Dayo’s latest scheme and driving a hoverbus of dubious condition through Lagos traffic. In a story of much grander scale, “Biscuit & Milk” by Dare Segun Falowo relates the chronicle of a pan-African ship fleeing into space to escape a dying Earth, finding instead a long journey of deep struggle and new definitions of home. And the collection’s opening tale, “The Blue House” by Dilman Dila, skillfully charts an artificial person working through the central human question of identity.

A number of the stories here concern the struggles of the ordinary or the small, in worlds both fantastical and futuristic. Many of these stories see people grappling with particular issues of social, economic, or political injustice. In Tananarive Due’s heartwrenching story “Ghost Ship,” the sadly relevant issue of the exploitation of migrants is spotlit in the tale of Florida, an American expatriate obliged by her crushing debts to smuggle a mysterious cargo by sea from South Africa to the United States (a dystopian US in which millions of nonwhites have fled to avoid racism and police violence). The dark evil of American racism is noted in another story, “Ruler of the Rear Guard” by Maurice Broaddus, concerning American student Sylvonne, who flees the horrors of her home country for a Ghana that has led the way towards welcoming home the people of the African Diaspora. Resistance to hatred and unjust power is seen in tales as disparate as WC Dunlap’s “March Magic,” which sees a group of righteous witches coming together with soul magic to bring dreams of racial progress into reality; Joshua Uchenna Omenga’s fabulistic folktale “The Deification of Igodo,” where a brutal ruler seeking to become a god faces deserved and dire consequences from divine entities; Tobias S. Buckell’s “The Sugar Mill,” where centuries of white injustices have soaked the land with ghosts and angry memories; “Mami Wataworks” by Russell Nichols, a tale of a terrible future in which increasingly scarce water becomes a weapon that the powerful use to hold down the ordinary and the innocent, but which is poised for radical change via the intelligence and creativity of clever Amaya; and Tlotlo Tsamasse’s visceral, searing “Peeling Time (Deluxe Edition),” which strikes a blow against the objectification and easy disposal of women in our human society, where trauma and toxic masculinity take on monstrous forms.

Beauty and the intensity of life and human existence abound throughout the collection, in stories of spaceships, spirits, and bodily transformations. The sheer variety and scope, combined with the geographical and cultural diversities on display, give a real richness to Africa Risen that makes it an excellent introduction for both scholars and casual readers of African and Afro-Diasporan traditions and demonstrates (though of course no proof is actually required) the robustness of the A + A-D speculative presence.

Jeremy Brett is an Associate Librarian at Cushing Memorial Library & Archives, where he is both Processing Archivist and the Curator of the Science Fiction & Fantasy Research Collection. He has also worked at the University of Iowa, the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, the National Archives and Records Administration-Pacific Region, and the Wisconsin Historical Society. He received his MLS and his MA in History from the University of Maryland – College Park in 1999. His professional interests include science fiction, fan studies, and the intersection of libraries and social justice.